Further Reading. Lady Scrope's Letter. List of Pilgrims' Demands. These are the demands sent to the King and Government on 2 nd December 1536. 1.

Suppression of heresies of Luther, Huss, Wycliffe, Melanchthon, Bucer, Barnes, Tyndale and others. 2. Pope to consecrate bishops but no pensions or first fruits (the first year's income from a clerical position) to be paid to the Pope, save a reasonable pension for defence of faith. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. Timeline. Aftermath. Henry was determined to break the power of the feudal lords, even if they had stood by him.

He knew that Norfolk and the others still saw themselves as having the right to rule under him, but the King was unwavering in his resolve to control the country through his own hand-picked men. The Earl of Northumberland played into his hands, when, possibly mentally ill, in physical decline, estranged from his wife and at loggerheads with his heirs, he surrendered his enormous landholding to the Crown before dying in 1537. The monasteries of Whalley, Bridlington, Jervaulx and Kirkstead, whose Abbots had been involved in the uprising, whether willingly or not, were confiscated by the Crown. Pressure was exerted on Robert Pyle, Abbot of Furness and his community to surrender their house voluntarily, which set the tone for the remainder of the monasteries across England and Wales.

Revenge. As Henry had hoped, the gentry and the Commons had fallen out, and the gentry now sat on the trials and commissions set up to try the Bigod rebels.

Norfolk marched into the area, and Martial Law was declared. Norfolk hanged some 74 rebels in Cumberland and Carlisle, in accordance with his orders to: "cause such dreadful execution to be doon upon a goode number of th'inhabitants of every town, village and hamlet...as well by the hanging up of them in trees as by the quartering of them and the setting up of their heddes and quarters....as may be a fearful spectacle"

Bigod's Rebellion. Having persuaded the rebels to stand down, Henry, aided by Cromwell, now embarked on a policy of "divide and rule".

He had been lucky in that none of the northern magnates had joined the rebels – Shrewsbury, Derby and Cumberland had all resisted and, in the former cases, led Government troops. Setting Out Demands. Having been told by the King that their demands were "dark and obscure", Aske set to work with Lord Darcy to elucidate exactly what the Pilgrims wanted.

He requested representatives of all of the Pilgrims to come to Pontefract where each request was weighed, discussed and approved by the various Captains in the Pilgrim army. Eventually a manifesto was agreed (Read it here). Aske was keen to have the support of the Church and asked Archbishop Lee to preach, no doubt hoping for sanctification of the rebels' aims. Lee, however, did not perform as expected, instead announcing that only princes were permitted to wield the sword. These demands were presented to Norfolk on 6 th December 1536. Negotiating with King & Ministers. The Duke of Norfolk, Henry's most experienced soldier, suggested that he and the Earl of Shrewsbury should join their two armies and line up along the south bank of the River Trent, preventing a crossing into the south.

Unfortunately, orders had already gone to Shrewsbury to move north, so the armies were too far apart to join forces before the Pilgrims could cross the river. Norfolk sent Lancaster Herald to the Pilgrims, urging them to avoid bloodshed by meeting to negotiate with him at Doncaster. Opinion in the rebel camp was divided. Yorkshire: Pilgrimage of Grace. Meanwhile, on 8 th October, rebellion had spread north of the Humber.

Robert Aske of Aytoun was the leader: a lawyer from north Yorkshire, he had, apparently, been constrained to join the rebels in early October, but he embraced the insurgency wholeheartedly, and he gave the whole uprising its religious flavour. Lincolnshire Rising. As early as September 1536 there had been stirrings of unrest in Dent, Yorkshire, but the real opener occurred around the three towns of Louth, Caistor and Horncastle in north-west Lincolnshire.

Three officials had descended on Louth, and the populace feared they were up to no good. The parish priest preached an inflammatory sermon, and his words were taken up by Nicholas Melton, a shoemaker, later known as Captain Cobbler. 3,000 men marched on Louth and the Commissioners fled. Some then joined the rebels, and four wrote to the King requesting a general pardon as the insurrection was caused by " the common voice and fame…of newe enhaunsements and importunate charges". Religious & Political Causes. Religion The father of modern Tudor history, G R Elton, rebuts the idea of the rebellion being motivated by a desire to have the monasteries restored, as, at the point the rebellion took off, only the smaller houses had been targeted, and few had actually been suppressed.

Later writers refute this, and argue that, even if restoration of the monasteries was not, per se, the aim of the rebels, their underlying religious conservatism, their fear of heresy and despoliation of their parish churches, coupled with rumours about the taxation of christenings and weddings were all root causes.

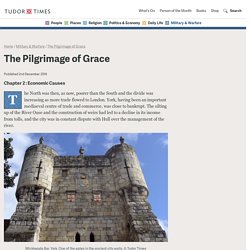

The Act of Supremacy of 1534 declared Henry VIII to be Head of the Church in England, and threw off the authority of the Pope. The change had been, somewhat reluctantly, accepted by the clergy at large, and whilst it is too much to say that no-one else much cared, it is apparent that the position of the Pope was not of huge interest to the population. Politics. Economic Causes. The North was then, as now, poorer than the South and the divide was increasing as more trade flowed to London.

York, having been an important mediaeval centre of trade and commerce, was close to bankrupt. The silting up of the River Ouse and the construction of weirs had led to a decline in its income from tolls, and the city was in constant dispute with Hull over the management of the river. It is perhaps significant that Hull, whilst permitting people to leave the city to join the Pilgrimage, did not declare for the rebels and only capitulated when confronted by force. There were also agricultural pressures. The Pilgrimage of Grace. The Pilgrimage of Grace was the most substantial uprising that ever confronted the Tudor throne.

It had the support of tens of thousands of the common people and a significant number of gentry and lesser nobles of the area of England north of the River Trent, an area always talked of as the "North". In black and white terms, and its place in sound-bite history, the Pilgrimage of Grace was a mass movement that wished to restore the Pope and the monasteries to England. But further consideration suggests that it was far more complex than that. Plots & Rebellions. Ambassadors. Ambassadors' reports form one of the most valuable sources of information we have about Europe in the period 1485-1603. Gossipy letters home from Paris, London, Edinburgh and Madrid tell us about James IV's mistresses, Katharine of Aragon's dislike of Henry VIII's beard, and Francis I's syphilis.

There was not an official civil service or foreign office in sixteenth century governments – people did not join the diplomatic service and work their way up the ladder only in that field. Instead an individual might serve the monarch in several capacities, of which foreign affairs was only one. Qualities that were deemed important were good language skills, particularly French, which was spoken at all the royal courts in Europe, and powerful connections both at home and abroad. James IV's Alliances. Further north again, in Scotland, James IV, having gained the throne through the overthrow of his father, spent most of his reign bringing the nobles under control and building an efficient and wealthy central government, as well as bringing the Western Isles under the Scottish Crown. Scotland, however, was in long-term alliance with France. Known as the Auld Alliance, the agreement was one of mutual defence against England. It probably began informally in the 1170s and was then formalised by a treaty signed in 1295 between John Balliol (1249 – 1314) and Philip IV (1268 – 1314) of France.

The Auld Alliance was renewed by every subsequent Scottish monarch, until James VI (1566 – 1625) and all of the French Kings except Louis XI (1423 – 1483). Over the years, generations of young Scots nobles travelled to France to fight there. Henry VII's Alliances. Further north, and, in the 1490s something of an also-ran, was Henry VII (1457 – 1509), King of England.

Against the odds, Henry Tudor had emerged from exile in Brittany to take up the mantle of the House of Lancaster and win the throne from the Yorkist King Richard III at Bosworth. Having won the throne of England in battle, Henry seemed to feel that he had nothing to prove by way of further wars, an idea that was considered rather un-chivalric at that time, although eminently sensible to modern ears. He pursued a policy of peace, wherever possible, although was able and prepared to back it up with military action, if necessary. Brittany & France. The Royal Pack of Cards... The trend towards centralisation began in France, after the Hundred Years War. The almost total ruin of the country meant that when King Charles VII finally emerged as the victor he was determined to build a wealthy, powerful monarchy that could mobilise the whole country against an invader and repress over-mighty barons. Charles VII's successors continued his policies.

With the emergence of a strong central government, kings, still believing that their subjects were divinely appointed to help them gain more territory, wealth and power, began to look for conquests. European Alliances. Foreign Relations. Coins in Scotland. Scotland too struck coins of varying value, but reduced the content of precious metal even further, with many coins being made of “billon”, a 50% amalgam of silver and copper.By the time of James III (1460 – 1488) lower grade and higher grade coins were in circulation at the same time, so a low-grade penny made of billon had a value of a penny, whilst a high grade one of pure silver was worth three pence. There were also “placks” and “half-placks” of billon, worth 4d and 2d respectively.

Coins in England. Early multiples of coins in England were the groat (4d) and half groat (2d.), then, under Henry VII, the first shillings, or “testoons” were created in 1502.The leap from 4d as the largest coin to 12d value was probably too great, and the coins were not that popular, and were not reissued until 1544, when Henry VIII reissued them at a considerably lower quantity of silver. At certain periods, half-pennies or farthings (quarter of a penny) were actually struck as coins, but this was rare: the smaller denominations were usually made by cutting a full penny into halves and quarters.The last farthing coins were struck in the reign of Edward VI, by which time they were so tiny, they were too difficult to handle.

A good example of fluctuating values is the sovereign, first minted under Henry VII as the gold equivalent of a pound sterling (20 shillings) – obviously easier to carry than a pound of silver! Money in Stewart & Tudor Times. On 15th February 1971, Britain and Ireland adopted decimal currency. Markets & Trade. St Michael & All Angels, Well. Churches. Jervaulx Abbey. In private hands, the ruins of the great Cistercian Abbey are sensitively managed and it is rather nice to wander amongst the ancient ruins with no interpretation boards or audio guides to distract from the atmosphere. Parking is on the opposite side of the road to the Abbey, where there is also a new cafe and a fabulous scale model of the abbey in its heyday.

It is worth looking at that before going to the grounds themselves so that a picture may be formed in your mind of the sheer scale of the structure. Cross the road and pass through an old kissing gate into a field which opens out into a gentle sloping valley, dotted with sheep - perhaps the very descendants of the monks' flocks. Abbeys & Priories. History. Visiting the Old Hall.

Location & Surroundings. Gainsborough Old Hall. Halls & Manor Houses. Snape Castle. Sizergh Castle. Restoration of Sudeley. Civil War. Tudor Period. Wars of the Roses. Early History. Visiting the Gardens. Visiting the Castle. Location and Surroundings. Sudeley Castle. Kendal Castle and Parish Church. Castles. History. Linlithgow Palace. Palaces. First Calls for Reform.

Reformation. Tudor Church Monuments. Death Rites Intro. Coronation Feast Chapter V. The Coronation Chapter IV. Procession Through The City Chapter III. By Barge To The Tower Of London Chapter II. Anne Boleyn's Coronation Chapter I. Pageants & Ceremonies Intro. Food & Drink Overview. Bread & Oats. Ale & Beer. Food & Drink Intro. Inheritance Of The Crown Chapter IV. Baronies & Peerages By Letters Patent Chapter III. Baronies By Writ Of Summons Chapter II. Family Wealth & Inheritance Chapter I. Post-Reformation Changes Chapter VIII. Getting Divorced Chapter VII. Sex Within Marriage Chapter VI. Whom Could You Marry? Chapter V. The Marriage Ceremony Chapter IV. What Made A Marriage? Chapter III. Secular v Religious Views Of Marriage Chapter II. Marriage Chapter I. Family Life Intro.