How was Schrodinger equation perceived pre-Born. Ab initio quantum chemistry methods. Density functional theory. DFT has been very popular for calculations in solid-state physics since the 1970s.

However, DFT was not considered accurate enough for calculations in quantum chemistry until the 1990s, when the approximations used in the theory were greatly refined to better model the exchange and correlation interactions. In many cases the results of DFT calculations for solid-state systems agree quite satisfactorily with experimental data. Computational costs are relatively low when compared to traditional methods, such as Hartree–Fock theory and its descendants based on the complex many-electron wavefunction.

Overview of method[edit] Although density functional theory has its conceptual roots in the Thomas–Fermi model, DFT was put on a firm theoretical footing by the two Hohenberg–Kohn theorems (H–K).[9] The original H–K theorems held only for non-degenerate ground states in the absence of a magnetic field, although they have since been generalized to encompass these.[10][11] where, for the and . . . Spin (physics) In quantum mechanics and particle physics, spin is an intrinsic form of angular momentum carried by elementary particles, composite particles (hadrons), and atomic nuclei.[1][2] Spin is a solely quantum-mechanical phenomenon; it does not have a counterpart in classical mechanics (despite the term spin being reminiscent of classical phenomena such as a planet spinning on its axis).[2] Spin is one of two types of angular momentum in quantum mechanics, the other being orbital angular momentum.

Orbital angular momentum is the quantum-mechanical counterpart to the classical notion of angular momentum: it arises when a particle executes a rotating or twisting trajectory (such as when an electron orbits a nucleus).[3][4] The existence of spin angular momentum is inferred from experiments, such as the Stern–Gerlach experiment, in which particles are observed to possess angular momentum that cannot be accounted for by orbital angular momentum alone.[5] Fermi hole. Neglecting the spin-orbit interaction, the wavefunction for the two electrons can be written as , where we have split the wavefunction into spatial and spin parts.

As mentioned above, needs to be antisymmetric, and so the antisymmetry can arise either from the spin part or the spatial part. There are 4 possible spin states for this system: However, only the first two are symmetric or anti-symmetric to electron exchange (which corresponds to exchanging 1 and 2). The first three are symmetric, whereas the last one is anti-symmetric. Or symmetric (requiring an anti-symmetric spin wavefunction): In the first case, the possible spin states are the three symmetric ones listed above, and this state is commonly referred to as a triplet.

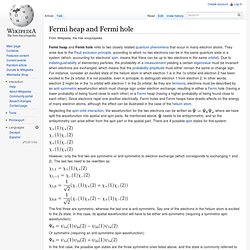

. , the probability amplitude tends to zero, meaning that the electrons are unlikely to be close to each other, which is referred to as Fermi hole and is responsible for the space-occupying properties of matter. Dill, Dan (2006). Fermi holes and Fermi heaps, Fall 2002, CH352 Physical Chemistry. You may have learned the "rule" that no more than two electrons can be in the same orbital.

If you have, you may also have puzzled about why such a rule is so. If you have decided, like many people who have been presented with just the rule without any explanation, that it has to do with electrical repulsion—that it reflects the electrons repelling one another due to their electrical charge—then you are in for a neat surprise. The "rule" instead traces to a deep algebraic property of nature that has nothing whatsoever to do with the charge on electrons! Perhaps you, like me, will find it fascinating that such a crucial aspect of the world has such a subtle origin. The essence is that many-electron wavefunctions must change sign when the labels on any two electrons are interchanged. Details of the origin and significance of Fermi holes and Fermi heaps are discussed elsewhere, but here are illustrations of Fermi hole and Fermi heaps in the carbon atom.

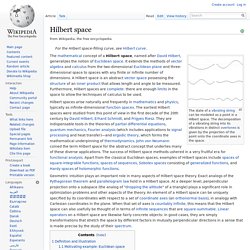

Hilbert space. The state of a vibrating string can be modeled as a point in a Hilbert space.

The decomposition of a vibrating string into its vibrations in distinct overtones is given by the projection of the point onto the coordinate axes in the space. Hilbert spaces arise naturally and frequently in mathematics and physics, typically as infinite-dimensional function spaces. The earliest Hilbert spaces were studied from this point of view in the first decade of the 20th century by David Hilbert, Erhard Schmidt, and Frigyes Riesz. They are indispensable tools in the theories of partial differential equations, quantum mechanics, Fourier analysis (which includes applications to signal processing and heat transfer)—and ergodic theory, which forms the mathematical underpinning of thermodynamics. John von Neumann coined the term Hilbert space for the abstract concept that underlies many of these diverse applications.

Definition and illustration[edit] Motivating example: Euclidean space[edit] Definition[edit] Ethan Hein's answer to Particle Physics: Why don't electrons crash into the nucleus.