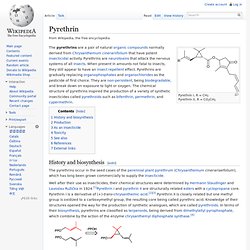

Pyrethrin. Pyrethrin I, R = CH3 Pyrethrin II, R = CO2CH3 The pyrethrins are a pair of natural organic compounds normally derived from Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium that have potent insecticidal activity.

Pyrethrins are neurotoxins that attack the nervous systems of all insects. When present in amounts not fatal to insects, they still appear to have an insect repellent effect. Turmeric's Cardiovascular Benefits Found To Be As Powerful As Exercise. By Sayer Ji Contributing Writer for Wake Up World Nothing can replace exercise, but turmeric extract does a pretty good job of producing some of the same cardiovascular health benefits, most notably in women undergoing age-associated adverse changes in arterial health.

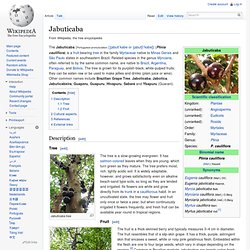

Despite the general lack of interest by conventional medical practitioners in turmeric’s role in preventing heart disease, there is a robust body of published research on its remarkable cardioprotective properties, with three dozen study abstracts on the topic available to view on GreenMedInfo’s database alone: turmeric’s cardioprective properties. Last year, GreedMedInfo reported on a study published in the American Journal of Cardiology that found turmeric extract reduces post-bypass heart attack risk by 56%. The 8-week long study involved 32 postmenopausal women who were assigned into 3 groups: a non-treatment control, exercise, and curcumin. References: Related articles: Further articles by Sayer Ji. Jabuticaba. The Jabuticaba (Portuguese pronunciation: [ʒabutiˈkabɐ or ʒabutʃiˈkabɐ]) (Plinia cauliflora) is a fruit-bearing tree in the family Myrtaceae native to Minas Gerais and São Paulo states in southeastern Brazil.

Related species in the genus Myrciaria, often referred to by the same common name, are native to Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Bolivia. The tree is grown for its purplish-black, white-pulped fruits; they can be eaten raw or be used to make jellies and drinks (plain juice or wine). Brachychiton rupestris. Brachyciton rupestris fruits.

The Queensland Bottle Tree (Brachychiton rupestris) originally classified in the family Sterculiaceae, which is now within Malvaceae, is native of Queensland, Australia. Its grossly swollen trunk gives it a remarkable appearance and gives rise to the name. As a succulent, drought-deciduous tree, it is tolerant of a range of various soils, and temperatures. It can grow to 18–20 meters (59–66 ft) in height and its trunk has the unique shape of a bottle. Its swollen trunk is primarily used for water storage. Synsepalum dulcificum. The berry itself has a low sugar content[7] and a mildly sweet tang. It contains a glycoprotein molecule, with some trailing carbohydrate chains, called miraculin.[8][9] When the fleshy part of the fruit is eaten, this molecule binds to the tongue's taste buds, causing sour foods to taste sweet.

At neutral pH, miraculin binds and blocks the receptors, but at low pH (resulting from ingestion of sour foods) miraculin binds protons and becomes able to activate the sweet receptors, resulting in the perception of sweet taste.[10] This effect lasts until the protein is washed away by saliva (up to about 60 minutes).[11] The names miracle fruit and miracle berry are shared by Gymnema sylvestre and Thaumatococcus daniellii,[2] which are two other species of plant used to alter the perceived sweetness of foods.

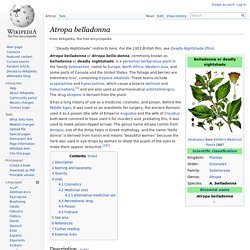

History[edit] Atropa belladonna. Atropa belladonna or Atropa bella-donna, commonly known as belladonna or deadly nightshade, is a perennial herbaceous plant in the family Solanaceae, native to Europe, North Africa, Western Asia, and some parts of Canada and the United States.

The foliage and berries are extremely toxic, containing tropane alkaloids. These toxins include scopolamine and hyoscyamine, which cause a bizarre delirium and hallucinations,[1] and are also used as pharmaceutical anticholinergics. Equisetum. A superficially similar but entirely unrelated flowering plant genus, mare's tail (Hippuris), is occasionally misidentified as "horsetail".

It has been suggested that the pattern of spacing of nodes in horsetails, wherein those toward the apex of the shoot are increasingly close together, inspired John Napier to discover logarithms.[4] Etymology[edit] The name "horsetail", often used for the entire group, arose because the branched species somewhat resemble a horse's tail. Amherstia. Amorphophallus titanum. Acacia. Acacia (/əˈkeɪʃə/ or /əˈkeɪsiə/), known commonly as acacia, thorntree, whistling thorn, or wattle, is a genus of shrubs and trees belonging to the subfamily Mimosoideae of the family Fabaceae, described by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1773 based on the African species Acacia nilotica.

Many non-Australian species tend to be thorny, whereas the majority of Australian acacias are not. All species are pod-bearing, with sap and leaves often bearing large amounts of tannins and condensed tannins that historically found use as pharmaceuticals and preservatives. The generic name derives from ἀκακία (akakia), the name given by early Greek botanist-physician Pedanius Dioscorides (middle to late first century) to the medicinal tree A. nilotica in his book Materia Medica.[2] This name derives from the Greek word for its characteristic thorns, ἀκίς (akis; "thorn").[3] The species name nilotica was given by Linnaeus from this tree's best-known range along the Nile river.

Classification[edit] Gunnera manicata. It is a large, clump-forming herbaceous perennial growing to 2.5 m (8 ft) tall by 4 m (13 ft) or more.

The leaves of Gunnera grow to an impressive size. Leaves with diameters well in excess of 4 ft (122 cm) are commonplace, with a spread of 10 ft (3 m) by 10 ft (3 m) on a mature plant. The underside of the leaf and the whole stalk have spikes on them. In early summer it bears tiny red-green flowers in conical branched panicles, followed by small, spherical fruit. However, it is primarily cultivated for its massive leaves.[1] This plant grows best in damp conditions e.g. by the side of garden ponds, but dislikes winter cold and wet. It has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[2] Dischidia major.