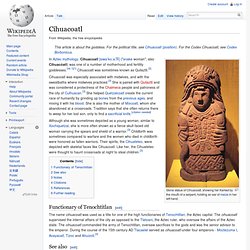

Cihuacoatl. Stone statue of Cihuacoatl, showing her framed by the mouth of a serpent, holding an ear of maize in her left hand.

In Aztec mythology, Cihuacoatl [siwaˈkoːaːt͡ɬ] ("snake woman"; also Cihuacóatl) was one of a number of motherhood and fertility goddesses. [nb 1][1] Cihuacoatl was sometimes known as Quilaztli.[2] Although she was sometimes depicted as a young woman, similar to Xochiquetzal, she is more often shown as a fierce skull-faced old woman carrying the spears and shield of a warrior.[3] Childbirth was sometimes compared to warfare and the women who died in childbirth were honored as fallen warriors. Their spirits, the Cihuateteo, were depicted with skeletal faces like Cihuacoatl. Like her, the Cihuateteo were thought to haunt crossroads at night to steal children.[3] Huitzilopochtli. Inti. Inti is the ancient Incan sun god.

He is revered as the national patron of the Inca state. Although most consider Inti the sun god, he is more appropriately viewed as a cluster of solar aspects, since the Inca divided his identity according to the stages of the sun.[1] Worshiped as a patron deity of the Inca Empire,[2] he is of unknown mythological origin.

The most common story says that he is the son of Viracocha, the god of civilization.[3] Legends and History[edit] Inti and his sister, Mama Quilla, the Moon goddess,[4] were generally considered benevolent deities. Inti ordered his children to build the Inca capital where a divine golden wedge they carried with them would penetrate the earth. Kinich Ahau. Kinich Ahau as a ruler, Classic period Kinich Ahau[pronunciation?]

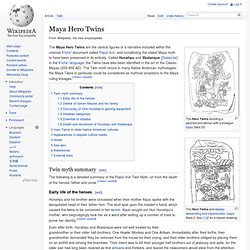

(K'inich Ajaw) is the 16th-century Yucatec name of the Maya sun god, designated as God G when referring to the codices. In the Classic period, God G is depicted as a middle-aged man with an aquiline nose, large square eyes, cross-eyed, and a filed incisor in the upper row of teeth. Maya Hero Twins. The Hero Twins shooting a perched bird demon with a blowgun.

Izapa Stela 25. The Maya Hero Twins are the central figures of a narrative included within the colonial K'iche' document called Popol Vuh, and constituting the oldest Maya myth to have been preserved in its entirety. Meri (mythology) Nanahuatzin. In Aztec mythology, the god Nanahuatzin or Nanahuatl (or Nanauatzin, the suffix -tzin implies respect or familiarity; Classical Nahuatl: Nanāhuātzin [nanaːˈwaːtsin]), the most humble of the gods, sacrificed himself in fire so that he would continue to shine on Earth as the sun, thus becoming the sun god.

Nanahuatzin means "full of sores. " In the Codex Borgia, Nanahuatl is represented as a man emerging from a fire. This was originally interpreted as an illustration of cannibalism. Aztec tradition[edit] The Aztecs had various myths about the creation, and Nanahuatzin participates in several. In this legend, which is the basis for most Nanahuatl myths, there had been four creations. The gods decide that the fifth, and possibly last, sun must offer up his life as a sacrifice in fire.

Nothing happens at first, but eventually two suns appear in the sky. Pipil tradition[edit] Sources[edit] Jump up ^ ANCIENT AMERICA, 9 = Ruud van Akkeren : Tzuywa : Place of the Gourd. Tohil. Tohil (/toˈχil/) (also spelt Tojil) was a deity of the K'iche' Maya in the Late Postclassic period of Mesoamerica.

At the time of the Spanish Conquest, Tohil was the patron god of the K'iche'.[1] Tohil's principal function was that of a fire deity and he was also both a sun god and the god of rain.[2] Tohil was also associated with mountains and he was a god of war, sacrifice and sustenance.[3] In the K'iche' epic Popul Vuh, after the first people were created, they gathered at the mythical Tollan, the Place of the Seven Caves, to receive their language and their gods. The K'iche', and others, there received Tohil.[4] Tohil demanded blood sacrifice from the K'iche' and so they offered their own blood and also that of sacrificed captives taken in battle.

Tonatiuh. In Aztec mythology, Tonatiuh (Nahuatl: Ōllin Tōnatiuh [oːlːin toːˈnatiʍ] "Movement of the Sun") was the sun god.[1] The Aztec people considered him the leader of Tollan, heaven.

He was also known as the fifth sun, because the Aztecs believed that he was the sun that took over when the fourth sun was expelled from the sky. Description[edit] Aztec theology held that each sun was a god with its own cosmic era, the Aztecs believed they were still in Tonatiuh's era. According to the Aztec creation myth, the god demanded human sacrifice as tribute and without it would refuse to move through the sky. It is said that 20,000 people were sacrificed each year to Tonatiuh and other gods, though this number is thought to be inflated either by the Aztecs, who wanted to inspire fear in their enemies, or the Spaniards, who wanted to vilify the Aztecs.

Xiuhtecuhtli. Statue of Xiuhtecuhtli in the British Museum.[1] In Aztec mythology, Xiuhtecuhtli [ʃiʍtekʷt͡ɬi] ("Turquoise Lord" or "Lord of Fire"),[2] was the god of fire, day and heat.[3] He was the lord of volcanoes,[4] the personification of life after death, warmth in cold (fire), light in darkness and food during famine.

He was also named Cuezaltzin [kʷeˈsaɬt͡sin] ("flame") and Ixcozauhqui [iʃkoˈsaʍki],[5] and is sometimes considered to be the same as Huehueteotl ("Old God"),[6] although Xiuhtecuhtli is usually shown as a young deity.[7] His wife was Chalchiuhtlicue.