Shakespeare's Sonnets. Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,And summer's lease hath all too short a date:Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,And often is his gold complexion dimmed,And every fair from fair sometime declines,By chance, or nature's changing course untrimmed:But thy eternal summer shall not fade,Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st,Nor shall death brag thou wander'st in his shade,When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st, So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

SHall I compare thee to a Summers day? Beautiful poem. Never fall in love with a poet... by A Thomas Hawkins. Poetry: Poems by the classic masters. Quote by W.B. Yeats: WINE comes in at the mouth And love comes in a... Trochee. A trochee /ˈtroʊkiː/ or choree, choreus, is a metrical foot used in formal poetry consisting of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one.

Foot (prosody) The foot is a purely metrical unit; there is no inherent relation to a word or phrase as a unit of meaning or syntax, though the interplay among these is an aspect of the individual poet's skill and artistry. Below are listed the names given to the poetic feet by classical metrics. The feet are classified first by the number of syllables in the foot (disyllables have two, trisyllables three, and tetrasyllables four) and secondarily by the pattern of vowel lengths (in classical languages) or syllable stresses (in English poetry) which they comprise. ¯ = stressed/long syllable, ˘ = unstressed/short syllable (macron and breve notation) Iambus (genre)

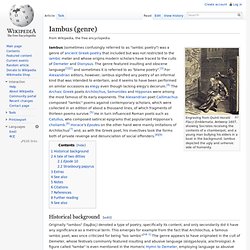

Engraving from Quinti Horatii Flacci Emblemata, Antwerp 1607, showing Socrates receiving the contents of a chamberpot, and a young man bullying his elders in a boat in the background.

Iambus depicted the ugly and unheroic side of humanity. Originally "iambos" (ἴαμβος) denoted a type of poetry, specifically its content, and only secondarily did it have any significance as a metrical term. This emerges for example from the fact that Archilochus, a famous iambic poet, was once criticized for being "too iambic"[nb 1] The genre appears to have originated in the cult of Demeter, whose festivals commonly featured insulting and abusive language (αἰσχρολογία, aischrologia). A figure called "Iambe" is even mentioned in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, employing language so abusive that the goddess forgets her sorrows and laughs instead.

The abuse of a divinity however is quite common in other cults too, as an ironic means of affirming piety: "Normality is reinforced by experiencing its opposite".[10] Sonnet 18. Sonnet 18, often alternately titled Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

, is one of the best-known of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. Part of the Fair Youth sequence (which comprises sonnets 1–126 in the accepted numbering stemming from the first edition in 1609), it is the first of the cycle after the opening sequence now described as the Procreation sonnets.

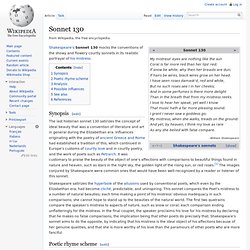

Paraphrase[edit] A facsimile of the original printing of Sonnet 18. The poem starts with a flattering question to the beloved—"Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? " The poet never describes anything specific about the beloved. Context[edit] Sonnet 19. William Shakespeare's Sonnet 19, sometimes considered the last of the opening group of sonnets, treats the theme of redemption of time through art.

Source and analysis[edit] G. Wilson Knight notes and analyzes the way in which "devouring" time is developed by trope in the first 19 poems; Jonathan Hart notes the reliance of Shakespeare's treatment on tropes from Ovid and Edmund Spenser. Sonnet 130. Shakespeare's Sonnet 130 mocks the conventions of the showy and flowery courtly sonnets in its realistic portrayal of his mistress.

Synopsis[edit] The last historian sonnet 130 satirizes the concept of ideal beauty that was a convention of literature and art in general during the Elizabethan era. Influences originating with the poetry of ancient Greece and Rome had established a tradition of this, which continued in Europe's customs of courtly love and in courtly poetry, and the work of poets such as Petrarch. It was customary to praise the beauty of the object of one's affections with comparisons to beautiful things found in nature and heaven, such as stars in the night sky, the golden light of the rising sun, or red roses.[1] The images conjured by Shakespeare were common ones that would have been well-recognized by a reader or listener of this sonnet. Poetic rhyme scheme[edit] Analysis[edit] Sonnet 116. Shakespeare's sonnet 116 was first published in 1609. Its structure and form are a typical example of the Shakespearean sonnet.[1] The poet begins by stating he should not stand in the way of true love.

Love cannot be true if it changes for any reason. Love is supposed to be constant, through any difficulties. Poems - Tennyson. From, Ulysses ...Though much is taken, much abides; and though We are not now that strength which in old days Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are, One equal temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Ulysses by Lord Alfred Tennyson. First published in 1842, no alterations were made in it subsequently.

This noble poem, which is said to have induced Sir Robert Peel to give Tennyson his pension, was written soon after Arthur Hallam's death, presumably therefore in 1833. "It gave my feeling," Tennyson said to his son, "about the need of going forward and braving the struggle of life perhaps more simply than anything in 'In Memoriam'. " Do Not Stand At My Grave And Weep.