Is Cancer Contagious? A healthy person cannot “catch” cancer from someone who has it.

There is no evidence that close contact or things like sex, kissing, touching, sharing meals, or breathing the same air can spread cancer from one person to another. Cancer cells from one person are generally unable to live in the body of another healthy person. A healthy person’s immune system recognizes foreign cells and destroys them, including cancer cells from another person.

Cancer transfer after organ transplant. Allotransplantation. It is not uncommon for patients and physicians to use the term "allograft" imprecisely to refer to either allograft (human-to-human) or xenograft (animal-to-human), but it is helpful scientifically (for those searching or reading the scientific literature) to maintain the more precise distinction.

[citation needed] Homografts may be called "homostatic" if they are biologically inert when transplanted, such as bone and cartilage.[2] An immune response against an allograft or xenograft is termed rejection. An allogenic bone marrow transplant can result in an immune attack, called Graft-versus-host disease. Clonally transmissible cancer. A parasitic cancer or transmissible cancer is a cancer cell or cluster of cancer cells that can be transmitted from animal to animal.

They are quite rare in both animals and humans. Parasitic cancers are distinct from cancers caused by infectious agents such as viruses and bacteria, which are more common. Aedes aegypti. The yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti is a mosquito that can spread the dengue fever, chikungunya and yellow fever viruses, and other diseases.

The mosquito can be recognized by white markings on legs and a marking in the form of a lyre on the thorax. The mosquito originated in Africa[2] but is now found in tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world.[3] Spread of disease and prevention[edit] Aedes aegypti can also contribute to spread reticulum cell sarcoma among Syrian hamsters.[5] The CDC traveler's page on preventing dengue fever suggests using mosquito repellents that contain DEET (N, N-diethylmetatoluamide, 20% to 30% concentration, but not more). Reticular connective tissue. Reticular connective tissue is a type of connective tissue.[1] It has a network of reticular fibers, made of type III collagen.[2] Reticular fibers are not unique to reticular connective tissue, but only in this type are they dominant.[3] Reticular fibers are synthesized by special fibroblasts called reticular cells.

The fibers are thin branching structures. Location[edit] Sarcoma. Classification[edit]

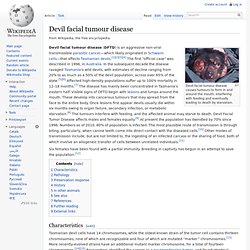

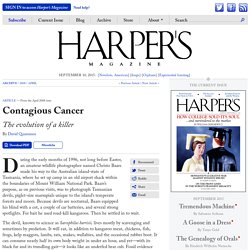

Devil facial tumour disease. Devil facial tumour disease causes tumours to form in and around the mouth, interfering with feeding and eventually leading to death by starvation.

Devil facial tumour disease (DFTD) is an aggressive non-viral transmissible parasitic cancer—which likely originated in Schwann cells—that affects Tasmanian devils.[1][2][3][4] The first "official case" was described in 1996, in Australia. In the subsequent decade the disease ravaged Tasmania's wild devils, with estimates of decline ranging from 20% to as much as a 50% of the devil population, across over 65% of the state.[5][6] Affected high-density populations suffer up to 100% mortality in 12–18 months.[7] The disease has mainly been concentrated in Tasmania's eastern half. Visible signs of DFTD begin with lesions and lumps around the mouth.

These develop into cancerous tumours that may spread from the face to the entire body. Six females have been found with a partial immunity. Poor Devils. Genetic diversity and population structure of the endangered marsupial Sarcophilus harrisii (Tasmanian devil) Tasmanian Devil Genome Project: Background. A Devil Indeed The Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) is a carnivorous marsupial found in the wild only in the Australian island state of Tasmania.

After the extinction in 1936 of the Tasmanian tiger (or Thylacine), another well-known carnivorous marsupial, the Tasmanian devil became the largest carnivorous marsupial in the world. They received their common name from the first European settlers, who called them “devils” when they encountered a fierce, noisy creature with large teeth, a “bad-temper”, and a habit of growling, yelling and screaming when annoyed, and which was always around at night. Contagious Cancer. During the early months of 1996, not long before Easter, an amateur wildlife photographer named Christo Baars made his way to the Australian island-state of Tasmania, where he set up camp in an old airport shack within the boundaries of Mount William National Park.

Baars’s purpose, as on previous visits, was to photograph Tasmanian devils, piglet-size marsupials unique to the island’s temperate forests and moors. Because devils are nocturnal, Baars equipped his blind with a cot, a couple of car batteries, and several strong spotlights. For bait he used road-kill kangaroos. Then he settled in to wait. The devil, known to science as Sarcophilus harrisii, lives mostly by scavenging and sometimes by predation. On his earlier visits, Baars had seen at least ten devils every night, and they were quick to adjust to his presence. More evidence of contagion began to accumulate. Tasmanian devil cancer tied to 'immortal' girl - Technology & science - Science - LiveScience. About 20 years ago, a female Tasmanian devil living in northeast Tasmania developed a facial tumor.

When she eventually died, she left some of her cancer cells behind. Her tumor lived on to kill another day, and has been sweeping through the endangered Tasmanian devil population ever since. The "immortal devil girl" was identified in a new study in which researchers sequenced the genetic blueprint, or genomes, of the Tasmanian devil's cancerous facial tumors.

"It’s a very bizarre cancer; it's spread by living cancer cells," study researcher Elizabeth Murchison, working with the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in the United Kingdom, told LiveScience. "The contagious cancer has arisen from the cells of a single girl devil that lived quite some time ago. These tumors are very special: They are spread through bites. Canine transmissible venereal tumor. Canine transmissible venereal tumor cytology Canine transmissible venereal tumor (CTVT), also called transmissible venereal tumor (TVT), Canine transmissible venereal sarcoma (CTVS), Sticker tumor and infectious sarcoma is a histiocytic tumor of the dog and other canids that mainly affects the external genitalia, and is transmitted from animal to animal during copulation. It is one of only three known transmissible cancers; another is Devil facial tumor disease, a cancer which occurs in Tasmanian devils. Canine TVT was initially described by Russian veterinarian M.A.

Novinsky (1841–1914) in 1876, when he demonstrated that the tumor could be transplanted from one dog to another by infecting them with tumor cells.[4] Biology[edit] Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumour (TVT) Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumour (TVT) INTRODUCTION Canine transmissible venereal tumour (TVT) or Sticker's sarcoma was first described by Hujard in 1820 in Europe and its name has been associated with Sticker who systematically studied it in the beginning of the 20th century. It is a neoplasm with unusual properties and unconventional clinical development, naturally occurring exclusively in dogs contaminated primarily by sexual contact and possibly by direct contact related with social behaviour (e.g., sniffing, licking of the genitalia, bite wounds during fights). It is almost always located at the genitalia of both sexes and is rarely found elsewhere in the body, while it metastasises in only a very few cases. Contagious Cancer, Beyond the Devils.

Few health issues strike a deeper chord of fear than that of cancer—your own body’s tissues being hijacked, turning against you and taking over. An estimated 1,596,670 new cancer cases (not including some types of skin cancer, which are not reported to the same registries as other cancers) will be diagnosed in the United States this year, and about 571,950 people will die from cancer during the same time. Roughly 11.7 million Americans alive today either have cancer or are in remission from it (see here for source of those statistics and more information). Meta-analysis of Risk Reduction Estimates Associated With Risk-Reducing Salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. + Author Affiliations Correspondence to: Timothy R. Rebbeck, PhD, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, 904 Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Dr, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6021 (e-mail: rebbeck@mail.med.upenn.edu).

Received May 28, 2008. Revision received October 22, 2008. Accepted October 31, 2008. Clonal Origin and Evolution of a Transmissible Cancer. Genetic Analysis of a Sarcoma Accidentally Transplanted from a Patient to a Surgeon. Pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma. Pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma (abbreviated PUS), also undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and previously malignant fibrous histiocytoma (abbreviated MFH), is a type of soft tissue sarcoma. It is considered a diagnosis of exclusion for sarcomas that cannot be more precisely categorized.[1][2] Epidemiology[edit] PUS is regarded as the most common soft tissue sarcoma of late adult life.

Oncovirus. Vaccines. Most of us know about vaccines given to healthy people to help prevent infections, such as measles and chicken pox. These vaccines use weakened or killed germs like viruses or bacteria to start an immune response in the body. Getting the immune system ready to defend against these germs helps keep people from getting infections. Most cancer vaccines work the same way, but they make the person’s immune system attack cancer cells.

Biological response modifiers. Biological response modifiers, also known as BRMs, are substances that the human body produces naturally, as well as something that scientists can create in a lab. These substances arouse the body's response to an infection. Vaccines. Panda’s are more diverse then Caucasian humans « Biochemistry, Molecular, Cellular & Developmental Biology. The survival of species is often linked to both population size and genetic diversity. With the latter we mean, that the more variation is present in a population, the more cards that species can bring to the table for selection.