Dropbox - Data Visualisation. Eric Berlow and Sean Gourley: Mapping ideas worth spreading. Clustering illusion. Up to 10,000 points randomly distributed inside a square with apparent "clumps" or clusters The clustering illusion is the tendency to erroneously consider the inevitable "streaks" or "clusters" arising in small samples from random distributions to be statistically significant.

The illusion is caused by a human tendency to underpredict the amount of variability likely to appear in a small sample of random or semi-random data.[1] Examples[edit] Gilovich, an early author on the subject, argued that the effect occurs for different types of random dispersions, including two-dimensional data such as clusters in the locations of impact of World War II V-1 flying bombs on maps of London; or seeing patterns in stock market price fluctuations over time.[1][2] Although Londoners developed specific theories about the pattern of impacts within London, a statistical analysis by R. D. Texas sharpshooter fallacy.

The Texas sharpshooter fallacy is an informal fallacy which is committed when differences in data are ignored, but similarities are stressed.

From this reasoning a false conclusion is inferred.[1] This fallacy is the philosophical/rhetorical application of the multiple comparisons problem (in statistics) and apophenia (in cognitive psychology). It is related to the clustering illusion, which refers to the tendency in human cognition to interpret patterns where none actually exist. Structure[edit] The Texas sharpshooter fallacy often arises when a person has a large amount of data at their disposal, but only focuses on a small subset of that data. Some factor other than the one attributed may give all the elements in that subset some kind of common property (or pair of common properties, when arguing for correlation).

Examples[edit] A Swedish study in 1992 tried to determine whether or not power lines caused some kind of poor health effects. Apophenia. Apophenia /æpɵˈfiːniə/ is the experience of perceiving patterns or connections in random or meaningless data.

The term is attributed to Klaus Conrad[1] by Peter Brugger,[2] who defined it as the "unmotivated seeing of connections" accompanied by a "specific experience of an abnormal meaningfulness", but it has come to represent the human tendency to seek patterns in random information in general, such as with gambling and paranormal phenomena.[3] Meanings and forms[edit] In 2008, Michael Shermer coined the word "patternicity", defining it as "the tendency to find meaningful patterns in meaningless noise".[6][7] In The Believing Brain (2011), Shermer says that we have "the tendency to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency", which Shermer calls "agenticity".[8]

Pareidolia: Why we see faces in hills, the Moon and toasties. People have long seen faces in the Moon, in oddly-shaped vegetables and even burnt toast, but a Berlin-based group is scouring the planet via satellite imagery for human-like features.

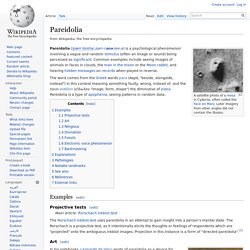

What's behind our desire to see faces in our surroundings, asks Lauren Everitt. Most people have never heard of pareidolia. But nearly everyone has experienced it. Anyone who has looked at the Moon and spotted two eyes, a nose and a mouth has felt the pull of pareidolia. It's "the imagined perception of a pattern or meaning where it does not actually exist", according to the World English Dictionary. German design studio Onformative is undertaking perhaps the world's largest and most systematic search for pareidolia. Google Faces will scan the entire globe several times over from different angles. It's certainly not the first to uncover faces where they don't actually exist. A chicken nugget shaped like US President George Washington earned more than £5,000 ($8,100) on eBay last year. Pareidolia. A satellite photo of a mesa in Cydonia, often called the Face on Mars.

Later imagery from other angles did not contain the illusion. Examples[edit] Projective tests[edit] The Rorschach inkblot test uses pareidolia in an attempt to gain insight into a person's mental state. The Rorschach is a projective test, as it intentionally elicits the thoughts or feelings of respondents which are "projected" onto the ambiguous inkblot images.

Art[edit] In his notebooks, Leonardo da Vinci wrote of pareidolia as a device for painters, writing "if you look at any walls spotted with various stains or with a mixture of different kinds of stones, if you are about to invent some scene you will be able to see in it a resemblance to various different landscapes adorned with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, wide valleys, and various groups of hills. Religious[edit] Divination[edit] Various European ancient divination practices involve the interpretation of shadows cast by objects.