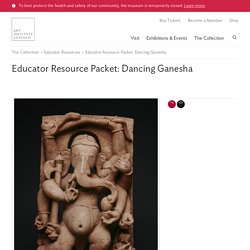

Asian Art Museum. Educator Resource Packet: Dancing Ganesha. This dancing, elephant-headed creature is Ganesha, Hinduism’s Lord of Beginnings and Remover of Obstacles.

Before beginning a school year, taking a trip, or starting a new business, Hindus pray to Ganesha for assistance, and he is prayed to at the start of all Hindu worship. Most temples have a separate area of worship dedicated to this elephant-headed god, and devotees first visit his image before proceeding to the principle deity’s shrine. Sculptures of Ganesha are often washed with water and adorned with flowers. Like most Hindu gods and goddesses (figure 3), Ganesha has multiple limbs, which indicate his supernatural power and cosmic nature.

In some of his many hands, the god holds an attribute, an object closely associated with his personality or history. Ganesha’s Attributes The most important of Ganesha’s attributes is his large elephant head. The god may be depicted with 2 to 16 arms. The Singh Twins unveil two new artworks revealing the wider story of a massacre. The Astounding Miniature Paintings of India’s Mughal Empire - Artsy. Navina Najat Haidar, a curator in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s department of , told Artsy that the “Mughal aesthetic is very unified, extending from architecture to painting—so painting and gardens are related.

Plus, the Mughal love of nature and observation of plants is closely linked to the representation of flora and gardens in painting.” Many Mughal gardens are preserved as UNESCO World Heritage sites; UNESCO describes Lahore’s Shalimar Gardens as the “apogee of Mughal artistic expression.” These gardens figure prominently in the miniature paintings, and both speak to the empire’s search for refinement and aesthetic pleasure. This refinement was far from immediate, however; the first few decades of the empire were unstable and chaotic. A 1540 uprising in Afghanistan forced Humāyūn, Babur’s son, to flee his court in order to seek military help. These two artists stayed at the court for the rest of their lives, and helped Humāyūn found and run an atelier of over 100 painters. Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India. Exotic and mysterious, both on paper and on stage.

I consider Rembrandt not only to be one of my favorite artists, but also one of my closest friends.

As a teenager, I fell in love with his art – so personal, so intimate, so mysterious… And, unlike so many Old Masters, we know quite a lot about his life. Left: Shah Jahan (detail), about 1656–61, Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn. Dark brown ink and dark brown wash with scratching out on Asian paper toned with light brown wash. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. The new exhibition at The Getty Museum, Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India, introduces us to a rather intriguing aspect of Rembrandt’s art during the late years of his life.

Left: 17. 20 of these drawings by Rembrandt are paired with the Indian paintings and drawings that inspired him. L: Attributed to Bichitr Indian (Mughal), active 1615–50. L: Cover, Klimt and Schiele Drawings. The Joffrey Ballet’s Romeo and Juliet. Now, let’s go back to LA. Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India. A closer look at Mughal Emperor Jahangir depicted on the hourglass throne. In episode 5 of the BBC series Civilisations, Simon Schama FBA magisterially discusses one of the most celebrated paintings in all of Mughal art, Jahangir preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings by Bichitr, c. 1615-18.

Simon Schama holding the painting by Bichitr, Jahangir preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings, c. 1615-18; 25.3 x 18.1cm. Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Schama’s narrative of the Triumph of Art (the title of the episode) has distinct echoes of Ernst Gombrich’s Art and Illusion, which, brilliant as that classic is, underpins a Euro-centric view of the meaning and development of style as a pursuit for pictorial illusion. Schama clearly finds greater empathy with the bursting three-dimensionality of western illusionism, which he states “body-slams the beholder with its meaty, muscular life-size figures,” over the miniature paintings of the Mughals who “could barely imagine the revolution in looking that was unfolding in western art.”