Stephan

MAR MAR MAR

Psychology. Psychology is an academic and applied discipline that involves the scientific study of mental functions and behaviors.[1][2] Psychology has the immediate goal of understanding individuals and groups by both establishing general principles and researching specific cases,[3][4] and by many accounts it ultimately aims to benefit society.[5][6] In this field, a professional practitioner or researcher is called a psychologist and can be classified as a social, behavioral, or cognitive scientist.

Psychologists attempt to understand the role of mental functions in individual and social behavior, while also exploring the physiological and biological processes that underlie cognitive functions and behaviors. While psychological knowledge is often applied to the assessment and treatment of mental health problems, it is also directed towards understanding and solving problems in many different spheres of human activity.

Etymology History Structuralism Functionalism Psychoanalysis Behaviorism Humanistic. Plato. Plato (/ˈpleɪtoʊ/; Greek: Πλάτων Plátōn "broad"pronounced [plá.tɔːn] in Classical Attic; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BCE) was a philosopher, as well as mathematician, in Classical Greece.

Seven Sages of Greece. The Seven Sages (of Greece) or Seven Wise Men (Greek: οἱ ἑπτὰ σοφοί, hoi hepta sophoi; c. 620 BC–550 BC) was the title given by ancient Greek tradition to seven early 6th century BC philosophers, statesmen and law-givers who were renowned in the following centuries for their wisdom.

Thales. Thales of Miletus (/ˈθeɪliːz/; Greek: Θαλῆς (ὁ Μιλήσιος), Thalēs; c. 624 – c. 546 BC) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Miletus in Asia Minor, and one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regard him as the first philosopher in the Greek tradition.[1] According to Bertrand Russell, "Western philosophy begins with Thales. "[2] Thales attempted to explain natural phenomena without reference to mythology and was tremendously influential in this respect. Almost all of the other Pre-Socratic philosophers follow him in attempting to provide an explanation of ultimate substance, change, and the existence of the world without reference to mythology.

Those philosophers were also influential and eventually Thales' rejection of mythological explanations became an essential idea for the scientific revolution. Democritus. Democritus (/dɪˈmɒkrɪtəs/; Greek: Δημόκριτος Dēmókritos, meaning "chosen of the people"; c. 460 – c. 370 BC) was an influential Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher. He is primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe.[3] Democritus was born in Abdera, Thrace[4] around 460 BC. His exact contributions are difficult to disentangle from those of his mentor Leucippus, as they are often mentioned together in texts.

Their speculation on atoms, taken from Leucippus, bears a passing and partial resemblance to the nineteenth-century understanding of atomic structure that has led some to regard Democritus as more of a scientist than other Greek philosophers; however, their ideas rested on very different bases.[5] Largely ignored in ancient Athens, Democritus was nevertheless well known to his fellow northern-born philosopher Aristotle. Life[edit] After returning to his native land he occupied himself with natural philosophy. Aristotle. Aristotle's views on physical science profoundly shaped medieval scholarship.

Alexander the Great. During his youth, Alexander was tutored by the philosopher Aristotle until the age of 16.

When he succeeded his father to the throne in 336 BC, after Philip was assassinated, Alexander inherited a strong kingdom and an experienced army. He had been awarded the generalship of Greece and used this authority to launch his father's military expansion plans. In 334 BC, he invaded the Achaemenid empire, ruled Asia Minor, and began a series of campaigns that lasted ten years.

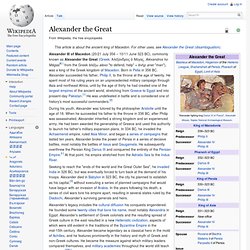

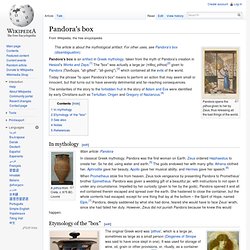

Alexander broke the power of Persia in a series of decisive battles, most notably the battles of Issus and Gaugamela. He subsequently overthrew the Persian King Darius III and conquered the entirety of the Persian Empire.i[›] At that point, his empire stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Indus River. Pandora. According to the myth, Pandora opened a jar (pithos), in modern accounts sometimes mistranslated as "Pandora's box" (see below), releasing all the evils of humanity—although the particular evils, aside from plagues and diseases, are not specified in detail by Hesiod—leaving only Hope inside once she had closed it again.[6] The Pandora myth is a kind of theodicy, addressing the question of why there is evil in the world.

Hesiod[edit] Hesiod, both in his Theogony (briefly, without naming Pandora outright, line 570) and in Works and Days, gives the earliest version of the Pandora story. Theogony[edit] The Pandora myth first appears in lines 560–612 of Hesiod's poem in epic meter, the Theogony (ca. 8th–7th centuries BC), without ever giving the woman a name. Pandora's box. Pandora opens the pithos given to her by Zeus, thus releasing all the bad things of the world.

Today the phrase "to open Pandora's box" means to perform an action that may seem small or innocent, but that turns out to have severely detrimental and far-reaching consequences.