List of people, items and places in Norse mythology.

Locals. Races. Numbers in Norse mythology. The numbers three and nine are significant numbers in Norse mythology and paganism.

Both numbers (and multiplications thereof) appear throughout surviving attestations of Norse paganism, in both mythology and cultic practice.[1] While the number three appears significant in many cultures, Norse mythology appears to put special emphasis on the number nine. Along with the number 27, both numbers also figure into the lunar Germanic calendar.[1] Attestations[edit] Three[edit] The number three occurs with great frequency in grouping individuals and artifacts: Nine[edit] The number nine is also a significant number: Notes[edit] ^ Jump up to: a b Simek (2007:232-233).Jump up ^ This last being from Völuspá, who will "come from on high", is found only in the Hauksbók manuscript.

References[edit] See also[edit] Runic alphabet. Runology is the study of the runic alphabets, runic inscriptions, runestones, and their history. Runology forms a specialised branch of Germanic linguistics. The earliest runic inscriptions date from around AD 150. The characters were generally replaced by the Latin alphabet as the cultures that had used runes underwent Christianisation, by approximately AD 700 in central Europe and AD 1100 in Northern Europe. However, the use of runes persisted for specialized purposes in Northern Europe. Until the early 20th century, runes were used in rural Sweden for decorative purposes in Dalarna and on Runic calendars.

The three best-known runic alphabets are the Elder Futhark (around AD 150–800), the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc (AD 400–1100), and the Younger Futhark (AD 800–1100). Ragnarök. The north portal of the 11th century Urnes stave church has been interpreted as containing depictions of snakes and dragons that represent Ragnarök In Norse mythology, Ragnarök is a series of future events, including a great battle foretold to ultimately result in the death of a number of major figures (including the gods Odin, Thor, Týr, Freyr, Heimdallr, and Loki), the occurrence of various natural disasters, and the subsequent submersion of the world in water.

Afterward, the world will resurface anew and fertile, the surviving and returning gods will meet, and the world will be repopulated by two human survivors. Norse paganism. Norse religion refers to the religious traditions of the Norsemen prior to the Christianization of Scandinavia, specifically during the Viking Age.

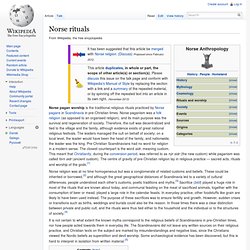

Norse religion is a subset of Germanic paganism, which was practiced in the lands inhabited by the Germanic tribes across most of Northern and Central Europe. Knowledge of Norse religion is mostly drawn from the results of archaeological field work, etymology and early written materials. Terminology[edit] Mjölnir pendants were worn by Norse pagans during the 9th to 10th centuries. This Mjolnir pendant was found at Bredsätra in Öland, Sweden. Norse religion was a cultural phenomenon, and — like most pre-literate folk beliefs — the practitioners probably did not have a name for their religion until they came into contact with outsiders or competitors. Sources[edit] Knowledge about Norse religion has been gathered from archaeological discoveries and from literature produced after the Christianization of Scandinavia.[2] Norse rituals. Norse pagan worship is the traditional religious rituals practiced by Norse pagans in Scandinavia in pre-Christian times.

Norse paganism was a folk religion (as opposed to an organised religion), and its main purpose was the survival and regeneration of society. Therefore, the cult was decentralized and tied to the village and the family, although evidence exists of great national religious festivals. The leaders managed the cult on behalf of society; on a local level, the leader would have been the head of the family, and nationwide, the leader was the king. Pre-Christian Scandinavians had no word for religion in a modern sense. The closest counterpart is the word sidr, meaning custom. Norse religion was at no time homogeneous but was a conglomerate of related customs and beliefs. It is not certain to what extent the known myths correspond to the religious beliefs of Scandinavians in pre-Christian times, nor how people acted towards them in everyday life.

Wiki. An undead völva, a Scandinavian seeress, tells the spear-wielding god Odin of what has been and what will be in Odin and the Völva by Lorenz Frølich (1895)