How do “today’s students” write, really? « previous post | next post » There was a cute "Things Kids Write" piece in the Wall Street Journal a few weeks ago (James Courter, "Teaching Taco Bell's Canon", 7/9/2012), with the subhead "Today's students don't read.

As a result, they have sometimes hilarious notions of how the written language represents what they hear. " Is it true that college students today are unprepared and unmotivated? That generalization does injustice to the numerous bright exceptions I saw in my 25 years of teaching composition to university freshmen. But in other cases the characterization is all too accurate. One big problem is that so few students are readers. There was the expected flurry of "o tempora o mores" comments: Maybe e-readers will bring us a hope of saving literacy. Larry Sanger Blog » Is there a new geek anti-intellectualism? Is there a new anti-intellectualism? I mean one that is advocated by Internet geeks and some of the digerati. I think so: more and more mavens of the Internet are coming out firmly against academic knowledge in all its forms. This might sound outrageous to say, but it is sadly true.

Let’s review the evidence. 1. Programmers have been saying for years that it’s unnecessary to get a college degree in order to be a great coder–and this has always been easy to concede. In 2001, along came Wikipedia, which gave everyone equal rights to record knowledge. Around the same time, some people began to criticize books as such, as an outmoded medium, and not merely because they are traditionally paper and not digital.

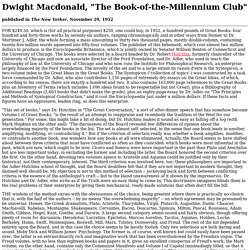

But nascent geek anti-intellectualism really began to come into focus around three years ago with the rise of Facebook and Twitter, when Nicholas Carr asked, “Is Google making us stupid?” In 2010, Edge took up the question, “Is the Internet changing the way you think?” Dwight Macdonald, "The Book-of-the-Millennium Club" Published in The New Yorker, November 29, 1952 FOR $249.50, which is (for all practical purposes) $250, one could buy, in 1952, a hundred pounds of Great Books: four hundred and forty-three works by seventy-six authors, ranging chronologically and in other ways from Homer to Dr.

Mortimer J. Adler, the whole forming a mass amounting to thirty-two thousand pages, mostly double-column, containing twenty-five million words squeezed into fifty-four volumes. The publisher of this behemoth, which cost almost two million dollars to produce, is the Encyclopaedia Britannica, which is jointly owned by Senator William Benton of Connecticut and the University of Chicago. The books were selected by a board headed by Dr. "This set of books," says Dr.

Books on Paper Fight Analog Distractions - Alexis Madrigal - Technology. We're worried.

The BRIGHT Future of Libraries - a Rant. So a friend of mine sent me this link which includes a bunch of articles about the future of libraries.

Against TED. George Bluth sells the Cornballer, Arrested Development When did TED lose its edge?

When did TED stop trying to collect smart people and instead collect people trying to be smart? Started as a one-off conference nearly 30 years ago, the TED (“Technology, Entertainment and Design”) phenomenon has grown to two large annual events and many smaller regional TEDx events, focusing mostly but not exclusively on technology. How TED Makes Ideas Smaller - Megan Garber - Technology. In 1874, the inventor Lewis Miller and the Methodist bishop John Heyl Vincent founded a camp for Sunday school teachers near Chautauqua, New York.

Two years later, Vincent reinstated the camp, training a collection of teachers in an outdoor summer school. Soon, what had started as an ad-hoc instructional course had become a movement: Secular versions of the outdoor schools, colloquially known as "Chautauquas," began springing up throughout the country, giving rise to an educational circuit featuring lectures and other performances by the intellectuals of the day. William Jennings Bryan, a frequent presenter at the Chautauquas, called the circuit a "potent human factor in molding the mind of the nation. " Teddy Roosevelt deemed it "the most American thing in America. " The cult of TED. 20 June 2012Last updated at 20:20 ET By Jon Kelly BBC News Magazine.

I Point To TED Talks and I Point to Kim Kardashian. That Is All. The Demise of Guys: Why Boys Are Struggling and What We Can Do About It, by Philip Zimbardo and Nikita Duncan.

TED Books. Kindle, Nook, iBooks, $2.99 Reviewed by Carl Zimmer Tonight, I want to talk to you about a national crisis. A global crisis. Prejudices and Antipathies. Knowlton.

The Death of the Lecture. Recently, I had a conversation around the lunch table with several of my colleagues. The discussion turned to the requirement to take pedagogical courses, now part of the criteria for getting an academic job at my university. Were these courses useful or just necessary? Do they teach something relevant for improving one’s teaching? As good scientists, we stopped discussing the courses and focused thereon on the definition of “teaching” or, more specifically, on what “good teaching” should stand for.