Thermodynamics. Annotated color version of the original 1824 Carnot heat engine showing the hot body (boiler), working body (system, steam), and cold body (water), the letters labeled according to the stopping points in Carnot cycle Thermodynamics applies to a wide variety of topics in science and engineering.

Statics. Statics is the branch of mechanics that is concerned with the analysis of loads (force and torque, or "moment") on physical systems in static equilibrium, that is, in a state where the relative positions of subsystems do not vary over time, or where components and structures are at a constant velocity.

When in static equilibrium, the system is either at rest, or its center of mass moves at constant velocity. Vectors[edit] Example of a beam in static equilibrium. The sum of force and moment is zero. A scalar is a quantity, such as mass or temperature, which only has a magnitude. A bold faced character VAn underlined character VA character with an arrow over it . Vectors can be added using the parallelogram law or the triangle law. Force[edit] Force is the action of one body on another. Forces are classified as either contact or body forces. Theory of relativity. The theory of relativity, or simply relativity in physics, usually encompasses two theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity.[1] Concepts introduced by the theories of relativity include: Measurements of various quantities are relative to the velocities of observers.

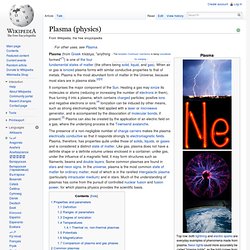

In particular, space contracts and time dilates.Spacetime: space and time should be considered together and in relation to each other.The speed of light is nonetheless invariant, the same for all observers. Quantum mechanics. Wavefunctions of the electron in a hydrogen atom at different energy levels.

Quantum mechanics cannot predict the exact location of a particle in space, only the probability of finding it at different locations.[1] The brighter areas represent a higher probability of finding the electron. Quantum mechanics (QM; also known as quantum physics, quantum theory, the wave mechanical model, or matrix mechanics), including quantum field theory, is a fundamental theory in physics which describes nature at the smallest scales of atoms and subatomic particles.[2] Quantum mechanics gradually arose from theories to explain observations which could not be reconciled with classical physics, such as Max Planck's solution in 1900 to the black-body radiation problem, and from the correspondence between energy and frequency in Albert Einstein's 1905 paper which explained the photoelectric effect. History[edit] In 1838, Michael Faraday discovered cathode rays. Where h is Planck's constant. Coulomb potential. Plasma (physics) Plasma (from Greek πλάσμα, "anything formed"[1]) is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and gas).

When air or gas is ionized plasma forms with similar conductive properties to that of metals. Plasma is the most abundant form of matter in the Universe, because most stars are in plasma state.[2][3] Artist's rendition of the Earth's plasma fountain, showing oxygen, helium, and hydrogen ions that gush into space from regions near the Earth's poles. The faint yellow area shown above the north pole represents gas lost from Earth into space; the green area is the aurora borealis, where plasma energy pours back into the atmosphere.[6] Plasma is loosely described as an electrically neutral medium of positive and negative particles (i.e. the overall charge of a plasma is roughly zero).

Range of plasmas. For plasma to exist, ionization is necessary. Lightning is an example of plasma present at Earth's surface. Optics. Optics is the branch of physics which involves the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it.[1] Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light.

Because light is an electromagnetic wave, other forms of electromagnetic radiation such as X-rays, microwaves, and radio waves exhibit similar properties.[1] Some phenomena depend on the fact that light has both wave-like and particle-like properties. Explanation of these effects requires quantum mechanics. When considering light's particle-like properties, the light is modelled as a collection of particles called "photons". Mechanics. Classical versus quantum[edit] The major division of the mechanics discipline separates classical mechanics from quantum mechanics.

Historically, classical mechanics came first, while quantum mechanics is a comparatively recent invention. Classical mechanics originated with Isaac Newton's laws of motion in Principia Mathematica; Quantum Mechanics was discovered in 1925. Both are commonly held to constitute the most certain knowledge that exists about physical nature. Classical mechanics has especially often been viewed as a model for other so-called exact sciences. Quantum mechanics is of a wider scope, as it encompasses classical mechanics as a sub-discipline which applies under certain restricted circumstances.

Mathematical physics. Kinematics. The study of kinematics is often referred to as the geometry of motion.[7] (See analytical dynamics for more detail on usage.)

To describe motion, kinematics studies the trajectories of points, lines and other geometric objects and their differential properties such as velocity and acceleration. Kinematics is used in astrophysics to describe the motion of celestial bodies and systems, and in mechanical engineering, robotics and biomechanics[8] to describe the motion of systems composed of joined parts (multi-link systems) such as an engine, a robotic arm or the skeleton of the human body.

The study of kinematics can be abstracted into purely mathematical functions. Fluid dynamics. Fluid dynamics offers a systematic structure—which underlies these practical disciplines—that embraces empirical and semi-empirical laws derived from flow measurement and used to solve practical problems.

The solution to a fluid dynamics problem typically involves calculating various properties of the fluid, such as velocity, pressure, density, and temperature, as functions of space and time. Before the twentieth century, hydrodynamics was synonymous with fluid dynamics. Electromagnetism. Dynamics (mechanics) Generally speaking, researchers involved in dynamics study how a physical system might develop or alter over time and study the causes of those changes.

In addition, Newton established the fundamental physical laws which govern dynamics in physics. By studying his system of mechanics, dynamics can be understood. In particular, dynamics is mostly related to Newton's second law of motion. However, all three laws of motion are taken into consideration, because these are interrelated in any given observation or experiment.[1] For classical electromagnetism, it is Maxwell's equations that describe the dynamics. Newton described force as the ability to cause a mass to accelerate. First law: If there is no net force on an object, then its velocity is constant. Newton's Laws of Motion are valid only in an inertial frame of reference Swagatam (25 March 011). Physical cosmology.

Physical cosmology is the study of the largest-scale structures and dynamics of the Universe and is concerned with fundamental questions about its formation, evolution, and ultimate fate.[1] For most of human history, it was a branch of metaphysics and religion. Cosmology as a science originated with the Copernican principle, which implies that celestial bodies obey identical physical laws to those on Earth, and Newtonian mechanics, which first allowed us to understand those physical laws.

Condensed matter physics. The diversity of systems and phenomena available for study makes condensed matter physics the most active field of contemporary physics: one third of all American physicists identify themselves as condensed matter physicists,[2] and The Division of Condensed Matter Physics (DCMP) is the largest division of the American Physical Society.[3] The field overlaps with chemistry, materials science, and nanotechnology, and relates closely to atomic physics and biophysics.

Theoretical condensed matter physics shares important concepts and techniques with theoretical particle and nuclear physics.[4] References to "condensed" state can be traced to earlier sources. Classical mechanics. Diagram of orbital motion of a satellite around the earth, showing perpendicular velocity and acceleration (force) vectors. In physics, classical mechanics and quantum mechanics are the two major sub-fields of mechanics. Classical mechanics is concerned with the set of physical laws describing the motion of bodies under the action of a system of forces.

The study of the motion of bodies is an ancient one, making classical mechanics one of the oldest and largest subjects in science, engineering and technology. It is also widely known as Newtonian mechanics. Aerodynamics. A vortex is created by the passage of an aircraft wing, revealed by smoke. Vortices are one of the many phenomena associated with the study of aerodynamics.

Formal aerodynamics study in the modern sense began in the eighteenth century, although observations of fundamental concepts such as aerodynamic drag have been recorded much earlier. Most of the early efforts in aerodynamics worked towards achieving heavier-than-air flight, which was first demonstrated by Wilbur and Orville Wright in 1903. Acoustics. Acoustics is the interdisciplinary science that deals with the study of all mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids including vibration, sound, ultrasound and infrasound. A scientist who works in the field of acoustics is an acoustician while someone working in the field of acoustics technology may be called an acoustical engineer. The application of acoustics is present in almost all aspects of modern society with the most obvious being the audio and noise control industries. The word "acoustic" is derived from the Greek word ἀκουστικός (akoustikos), meaning "of or for hearing, ready to hear"[2] and that from ἀκουστός (akoustos), "heard, audible",[3] which in turn derives from the verb ἀκούω (akouo), "I hear".[4] The Latin synonym is "sonic", after which the term sonics used to be a synonym for acoustics[5] and later a branch of acoustics.[6] Frequencies above and below the audible range are called "ultrasonic" and "infrasonic", respectively.