Integrative Thinking « Roger Martin. In this primer on the problem-solving power of “integrative thinking,” Martin draws on more than 50 management success stories, including the masterminds behind The Four Seasons, Proctor & Gamble and eBay, to demonstrate how, like the opposable thumb, the “opposable mind”-Martin’s term for the human brain’s ability “to hold two conflicting ideas in constructive tension”-is an intellectually advantageous evolutionary leap through which decision-makers can synthesize “new and superior ideas.”

Using this strategy, Martin focuses on what leaders think, rather than what they do. Among anecdotes and examples steering readers to change their thinking about thinking, Martin gives readers specific strategies for understanding their own “personal knowledge system” (by parsing inherent qualities of “stance,” “tools” and “experience”), as well as for taking advantage of the “richest source of new insight into a problem,” the “opposing model.” Power (philosophy) In social science and politics, power is the ability to influence or control the behavior of people.

The term authority is often used for power perceived as legitimate by the social structure. Power can be seen as evil or unjust, but the exercise of power is accepted as endemic to humans as social beings. In the corporate environment, power is often expressed as upward or downward. With downward power, a company's superior influences subordinates. When a company exerts upward power, it is the subordinates who influence the decisions of the leader (Greiner & Schein, 1988). The use of power need not involve coercion (force or the threat of force). Much of the recent sociological debate on power revolves around the issue of the enabling nature of power. Power may be held through: Integrative thinking. Integrative Thinking is a field which was originated by Graham Douglas in 1986.[1][2][3] He describes Integrative Thinking as the process of integrating intuition, reason and imagination in a human mind with a view to developing a holistic continuum of strategy, tactics, action, review and evaluation for addressing a problem in any field.

A problem may be defined as the difference between what one has and what one wants. Integrative Thinking may be learned by applying the SOARA (Satisfying, Optimum, Achievable Results Ahead) Process devised by Graham Douglas to any problem. The SOARA Process employs a set of triggers of internal and external knowledge. This facilitates associations between what may have been regarded as unrelated parts of a problem. Definition used by Roger Martin[edit] The Rotman School of Management defines integrative thinking as: The website continues: "Integrative thinkers build models rather than choose between them.

Overconfidence effect. The overconfidence effect is a well-established bias in which someone's subjective confidence in their judgments is reliably greater than their objective accuracy, especially when confidence is relatively high.[1] For example, in some quizzes, people rate their answers as "99% certain" but are wrong 40% of the time.

It has been proposed that a metacognitive trait mediates the accuracy of confidence judgments,[2] but this trait's relationship to variations in cognitive ability and personality remains uncertain.[1] Overconfidence is one example of a miscalibration of subjective probabilities. Demonstration[edit] The most common way in which overconfidence has been studied is by asking people how confident they are of specific beliefs they hold or answers they provide. The data show that confidence systematically exceeds accuracy, implying people are more sure that they are correct than they deserve to be.

Framing (social sciences) In the social sciences, framing is a set of concepts and theoretical perspectives on how individuals, groups, and societies organize, perceive, and communicate about reality.

Framing is the social construction of a social phenomenon often by mass media sources, political or social movements, political leaders, or other actors and organizations. It is an inevitable process of selective influence over the individual's perception of the meanings attributed to words or phrases. It is generally considered in one of two ways: as frames in thought, consisting of the mental representations, interpretations, and simplifications of reality, and frames in communication, consisting of the communication of frames between different actors.[1] The effects of framing can be seen in many journalism applications. With the same information being used as a base, the ‘frame’ surrounding the issue can change the reader’s perception without having to alter the actual facts.

Confirmation bias. Tendency of people to favor information that confirms their beliefs or values.

Sunk costs. In economics and business decision-making, a sunk cost is a retrospective (past) cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered.

Sunk costs are sometimes contrasted with prospective costs, which are future costs that may be incurred or changed if an action is taken. Both retrospective and prospective costs may be either fixed (continuous for as long as the business is in operation and unaffected by output volume) or variable (dependent on volume) costs. [1] Sherman notes, however, that many economists consider it a mistake to classify sunk costs as "fixed" or "variable. " For example, if a firm sinks $1 million on an enterprise software installation, that cost is "sunk" because it was a one-time expense and cannot be recovered once spent.

A "fixed" cost would be monthly payments made as part of a service contract or licensing deal with the company that set up the software. Sunk costs should not affect the rational decision-maker's best choice. Status quo bias. Status quo bias is a cognitive bias; a preference for the current state of affairs.

The current baseline (or status quo) is taken as a reference point, and any change from that baseline is perceived as a loss. Status quo bias should be distinguished from a rational preference for the status quo ante, as when the current state of affairs is objectively superior to the available alternatives, or when imperfect information is a significant problem. A large body of evidence, however, shows that status quo bias frequently affects human decision-making. Status quo bias interacts with other non-rational cognitive processes such as loss aversion, existence bias, endowment effect, longevity, mere exposure, and regret avoidance.

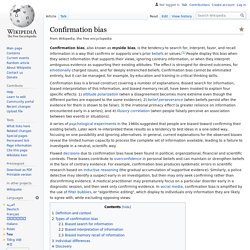

Decision making. Sample flowchart representing the decision process to add a new article to Wikipedia.

Decision-making can be regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several alternative possibilities. Every decision-making process produces a final choice[1] that may or may not prompt action.Decision making is one of the central activities of management and is a huge part of any process of implementation.

Good decision making is an essential skill to become an effective leader and for a successful career. Decision making is the study of identifying and choosing alternatives based on the values and preferences of the decision maker. Overview[edit] Cognitive bias. Systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment Although it may seem like such misperceptions would be aberrations, biases can help humans find commonalities and shortcuts to assist in the navigation of common situations in life.[5] Some cognitive biases are presumably adaptive.

Cognitive biases may lead to more effective actions in a given context.[6] Furthermore, allowing cognitive biases enables faster decisions which can be desirable when timeliness is more valuable than accuracy, as illustrated in heuristics.[7] Other cognitive biases are a "by-product" of human processing limitations,[1] resulting from a lack of appropriate mental mechanisms (bounded rationality), impact of individual's constitution and biological state (see embodied cognition), or simply from a limited capacity for information processing.[8][9] Overview[edit] The "Linda Problem" illustrates the representativeness heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983[14]). Anchoring. Anchoring or focalism is a cognitive bias that describes the common human tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the "anchor") when making decisions. During decision making, anchoring occurs when individuals use an initial piece of information to make subsequent judgments.

Once an anchor is set, other judgments are made by adjusting away from that anchor, and there is a bias toward interpreting other information around the anchor. For example, the initial price offered for a used car sets the standard for the rest of the negotiations, so that prices lower than the initial price seem more reasonable even if they are still higher than what the car is really worth.

Focusing effect[edit] Organizational culture. Organizational culture is the behavior of humans who are part of an organization and the meanings that the people reach to their actions. Culture includes the organization values, visions, norms, working language, systems, symbols, beliefs, and habits. It is also the pattern of such collective behaviors and assumptions that are taught to new organizational members as a way of perceiving, and even thinking and feeling.

Organizational culture affects the way people and groups interact with each other, with clients, and with stakeholders. Ravasi and Schultz (2006) state that organizational culture is a set of shared mental assumptions that guide interpretation and action in organizations by defining appropriate behavior for various situations.[1] At the same time although a company may have their "own unique culture", in larger organizations, there is a diverse and sometimes conflicting cultures that co-exist due to different characteristics of the management team. Usage[edit] Types[edit] Emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence (EI) can be defined as the ability to monitor one's own and other people's emotions, to discriminate between different emotions and label them appropriately, and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior.[1] There are three models of EI.

The ability model, developed by Peter Salovey and John Mayer, focuses on the individual's ability to process emotional information and use it to navigate the social environment.[2] The trait model as developed by Konstantin Vasily Petrides, "encompasses behavioral dispositions and self perceived abilities and is measured through self report" [3] The final model, the mixed model is a combination of both ability and trait EI, focusing on EI being an array of skills and characteristics that drive leadership performance, as proposed by Daniel Goleman.[4] It has been argued that EI is either just as important as one's intelligence quotient (IQ). History[edit] Definitions[edit] Ability model[edit]