Jordan curve theorem. Illustration of the Jordan curve theorem. The Jordan curve (drawn in black) divides the plane into an "inside" region (light blue) and an "outside" region (pink). The Jordan curve theorem is named after the mathematician Camille Jordan, who found its first proof. For decades, mathematicians generally thought that this proof was flawed and that the first rigorous proof was carried out by Oswald Veblen.

However, this notion has been challenged by Thomas C. Hales and others. Curve orientation. In mathematics, a positively oriented curve is a planar simple closed curve (that is, a curve in the plane whose starting point is also the end point and which has no other self-intersections) such that when traveling on it one always has the curve interior to the left (and consequently, the curve exterior to the right).

If in the above definition one interchanges left and right, one obtains a negatively oriented curve. Crucial to this definition is the fact that every simple closed curve admits a well-defined interior; that follows from the Jordan curve theorem. All simple closed curves can be classified as negatively oriented (clockwise), positively oriented (counterclockwise), or non-orientable. Klein bottle. Structure of a three-dimensional Klein bottle In mathematics, the Klein bottle /ˈklaɪn/ is an example of a non-orientable surface; informally, it is a surface (a two-dimensional manifold) in which notions of left and right cannot be consistently defined.

Other related non-orientable objects include the Möbius strip and the real projective plane. Whereas a Möbius strip is a surface with boundary, a Klein bottle has no boundary (for comparison, a sphere is an orientable surface with no boundary). The Klein bottle was first described in 1882 by the German mathematician Felix Klein. It may have been originally named the Kleinsche Fläche ("Klein surface") and that this was incorrectly interpreted as Kleinsche Flasche ("Klein bottle"), which ultimately led to the adoption of this term in the German language as well.[1] Construction[edit] Real projective plane. In mathematics, the real projective plane is an example of a compact non-orientable two-dimensional manifold, that is, a one-sided surface.

It cannot be embedded in standard three-dimensional space without intersecting itself. It has basic applications to geometry, since the common construction of the real projective plane is as the space of lines in R3 passing through the origin. (0, y) ~ (1, 1 − y) for 0 ≤ y ≤ 1 and (x, 0) ~ (1 − x, 1) for 0 ≤ x ≤ 1, as in the leftmost diagram on the right. Examples[edit] Projective geometry is not necessarily concerned with curvature and the real projective plane may be twisted up and placed in the Euclidean plane or 3-space in many different ways.[1] Some of the more important examples are described below. The projective sphere[edit] Consider a sphere, and let the great circles of the sphere be "lines", and let pairs of antipodal points be "points".

Orientability. A torus is an orientable surface In mathematics, orientability is a property of surfaces in Euclidean space measuring whether it is possible to make a consistent choice of surface normal vector at every point.

A choice of surface normal allows one to use the right-hand rule to define a "clockwise" direction of loops in the surface, as needed by Stokes' theorem for instance. More generally, orientability of an abstract surface, or manifold, measures whether one can consistently choose a "clockwise" orientation for all loops in the manifold. Equivalently, a surface is orientable if a two-dimensional figure such as in the space cannot be moved (continuously) around the space and back to where it started so that it looks like its own mirror image Orientable surfaces[edit] Ruled surface. Möbius strip. A Möbius strip made with a piece of paper and tape.

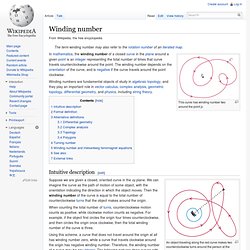

If an ant were to crawl along the length of this strip, it would return to its starting point having traversed the entire length of the strip (on both sides of the original paper) without ever crossing an edge. The Möbius strip or Möbius band (UK /ˈmɜrbiəs/ or US /ˈmoʊbiəs/; German: [ˈmøːbi̯ʊs]), also Mobius or Moebius, is a surface with only one side and only one boundary component. The Möbius strip has the mathematical property of being non-orientable. It can be realized as a ruled surface. It was discovered independently by the German mathematicians August Ferdinand Möbius and Johann Benedict Listing in 1858.[1][2][3] Winding number. The term winding number may also refer to the rotation number of an iterated map.

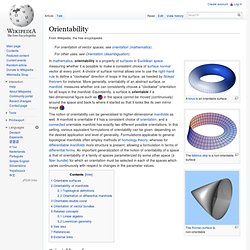

This curve has winding number two around the point p. Winding numbers are fundamental objects of study in algebraic topology, and they play an important role in vector calculus, complex analysis, geometric topology, differential geometry, and physics, including string theory. Intuitive description[edit] An object traveling along the red curve makes two counterclockwise turns around the person at the origin.

Using this scheme, a curve that does not travel around the origin at all has winding number zero, while a curve that travels clockwise around the origin has negative winding number. Formal definition[edit]