http://patterninislamicart.com/

Related: art & design • singalong468 • Sequenze, frattali, geometrie sacrePaul Klee: Triumph of a 'degenerate' "I cannot be grasped in the here and now," the artist Paul Klee wrote as the first line of his own tombstone epitaph. Which in one sense is the opposite of the truth. There are few among the leading Modernist painters who are not more readily known than Klee, with his spindly lines and squared block colours, and even fewer who are more readily loved. Picasso and Matisse seize you with their vision, Klee has the knack of making you feel a partner in it.

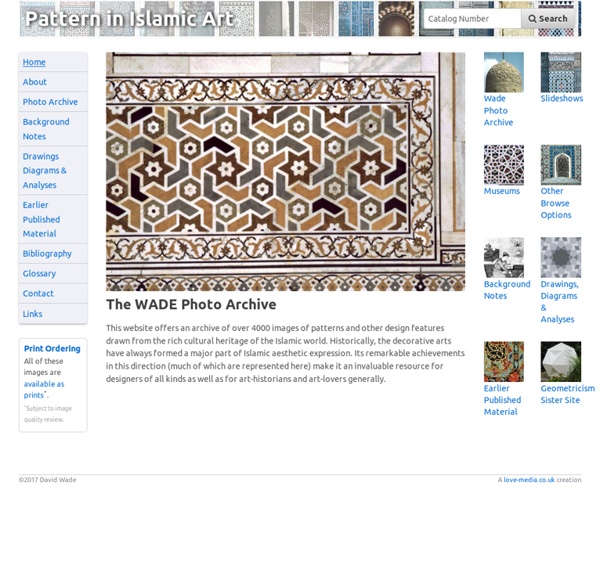

Teachers' resource: Maths and Islamic art & design Tiles, fritware with lustre decoration, Kashan, Iran, 13th-14th century, Museum no. 1074-1875. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London This resource provides a variety of information and activities that teachers may like to use with their students to explore the Islamic Middle East collections at the V&A. It can be used to support learning in Maths and Art. Included in this resource are sections on: Principles of Islamic art and design Pre-visit activities Activities to do in the museum Activities to do back at school Islamic art explores the geometric systems that depend upon the regular division of the circle and the study of Islamic art increases appreciation and understanding of geometry.

Photo to Oil Painting Converter - Oil painting photo effect online Sending your request to Picture to People server ... It can take a minute to calculate, so please wait. If you receive a file to download, after saving it, refresh this page pressing F5. RDF 1.1 Primer Abstract This primer is designed to provide the reader with the basic knowledge required to effectively use RDF. It introduces the basic concepts of RDF and shows concrete examples of the use of RDF. Secs. 3-5 can be used as a minimalist introduction into the key elements of RDF. Sacred Geometry Introductory Tutorial by Bruce Rawles Great site on natural law and basics of sacred geometry….check it out!-A.M. In nature, we find patterns, designs and structures from the most minuscule particles, to expressions of life discernible by human eyes, to the greater cosmos. These inevitably follow geometrical archetypes, which reveal to us the nature of each form and its vibrational resonances.

Powerfully Moving Brush Strokes UK-based contemporary painter Paul Wright creates incredibly intimate, yet somewhat abstract, oil paintings that draw the viewer in. His work focuses primarily on people and faces, but he occasionally ventures off to depict clothing and objects to reflect the people who own them. Wright captures the essence of his characters.

The Meaning of Sacred Geometry Most of us tend to think of geometry as a relatively dry, if not altogether boring, subject remembered from our Middle school years, consisting of endless axioms, definitions, postulates and proofs, hearkening back, in fact, to the methodology of Euclids Elements, in form and structure a masterly exposition of logical thinking and mental training but not the most thrilling read one might undertake in their leisure time. While the modern, academic approach to the study of geometry sees it as the very embodiment of rationalism and left brain, intellectual processes, which indeed it is, it has neglected the right brain, intuitive, artistic dimension of the subject. Sacred geometry seeks to unite and synthesize these two dynamic and complementary aspects of geometry into an integrated whole.

“The Raft of the Medusa” – Art A Fact There are few better examples of technical mastery than Gericault’s tale of the poor shipwrecked souls of the French Naval Ship, The Medusa. Imagine an artist today creating a HUGE scene of the BP oil spills from a few years back – quite controversial right? But Gericault new that painting a scene of contemporary history could launch his career. Only 15 people survived the shipwreck and raft ordeal (of the original 147 that began on the raft!)