What makes a great essay? The Essay, an Exercise in Doubt. Draft is a series about the art and craft of writing.

I am an essayist, for better or worse. I don’t suppose many young people dream of becoming essayists. Even as nerdy and bookish a child as I was fantasized about entering the lists of fiction and poetry, those more glamorous, noble genres on which Nobels, Pulitzers and National Book Awards are annually bestowed. So if Freud was right in saying that we can be truly happy only when our childhood ambitions are fulfilled, then I must be content to be merely content. I like the freedom that comes with lowered expectations. Ever since Michel de Montaigne, the founder of the modern essay, gave as a motto his befuddled “What do I know?” According to Theodor Adorno, the iron law of the essay is heresy.

Alexander Glandien Recently, with fiercely increased competition for admission to the better colleges, the “common app” essay has become an obsessive focus on the part of high school administrators, parents and students. Crafting the Personal Essay. Crafting the Personal Essay: An Interview with Dinty W. Moore. Crafting the Personal Essay: An Interview with Dinty W.

Moore By Erika Dreifus I met Dinty W. Moore a number of years ago through the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, of which he is now president. His concern for writing pedagogy, and his particular expertise in nonfiction, impressed me at the start, and they continue to inspire me. Dinty W. Please welcome Dinty W. ERIKA DREIFUS (ED): Dinty, what inspired you to write Crafting the Personal Essay, and why at this time? DINTY W. ED: Whom do you envision as the ideal reader(s) for this book? DWM: The urge to share our best thoughts, to display our carefully-constructed ideas and discoveries to other souls, is fairly universal. Frankly, there is a pretty good market for the essay too: from women’s magazines, to The New York Times, to literary magazines, to the Huffington Post. ED: In this book, you emphasize the importance of curiosity. But that’s what I imagine about the book here at the beginning. Michel de Montaigne.

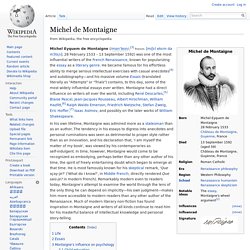

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (/mɒnˈteɪn/;[3] French: [miʃɛl ekɛm də mɔ̃tɛɲ]; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592) was one of the most influential writers of the French Renaissance, known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre.

He became famous for his effortless ability to merge serious intellectual exercises with casual anecdotes[4] and autobiography—and his massive volume Essais (translated literally as "Attempts" or "Trials") contains, to this day, some of the most widely influential essays ever written. Montaigne had a direct influence on writers all over the world, including René Descartes,[5] Blaise Pascal, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Albert Hirschman, William Hazlitt,[6] Ralph Waldo Emerson, Friedrich Nietzsche, Stefan Zweig, Eric Hoffer,[7] Isaac Asimov, and possibly on the later works of William Shakespeare. In his own lifetime, Montaigne was admired more as a statesman than as an author. Life[edit] Portrait of Michel de Montaigne by Dumonstier around 1578. Essais[edit] Donald Murray (writer) Donald Morrison Murray (1924 – December 30, 2006) was a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist and long-time teacher (eventually Professor Emeritus of English at the University of New Hampshire).[1] He wrote for many journals, authored several books on the art of writing and teaching, and served as writing coach for several national newspapers.

After writing multiple editorials about changes in American military policy for the Boston Herald, he won the 1954 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing.[2] For twenty years, he wrote the Boston Globe's "Over 60" column, eventually renamed "Now And Then".[1] He taught at the University of New Hampshire for twenty-six years.[3] Murray lived in Durham, New Hampshire with his wife, Minnie Mae. They were married for 54 years.[4] Murray and his wife had three children, Anne, Hannah, and Lee. Murray chronicled his relationship with writing until the day he died. Murray encouraged the writer to embrace and not fear self-exposure. Shitty first drafts. Don't Tell, Show. Once More to the Lake.