Baba Yaga. Baphomet. "Bahomet" redirects here.

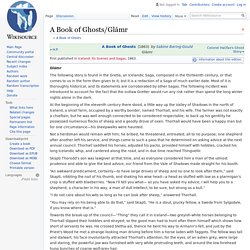

It is not to be confused with Bahamut. The 19th century image of a Sabbatic Goat, created by Eliphas Levi. The arms bear the Latin words SOLVE (separate) and COAGULA (join together), i.e., the power of "binding and loosing" usurped from God and, according to Catholic tradition, from the ecclesiastical hierarchy acting as God's representative on Earth. The original goat pentagram first appeared in the book "La Clef de la Magie Noire" by French occultist Stanislas de Guaita, in 1897. This symbol would later become synonymous with Baphomet, and is commonly referred to as the Goat of Mendes or Sabbatic Goat.

Baphomet (/ˈbæfɵmɛt/; from Medieval Latin Baphometh, Baffometi, Occitan Bafometz) is a term originally used to describe an idol or other deity that the Knights Templar were accused of worshiping, and that subsequently was incorporated into disparate occult and mystical traditions. §History[edit] The name Baphomet comes up in several of these confessions. Draugr. "Sea-troll" of modern Scandinavian folklore as depicted by the Norwegian painter Theodor Kittelsen The draugr or draug (Old Norse: draugr, plural draugar; modern Icelandic: draugur, Faroese: dreygur and Norwegian, Swedish and Danish draugen), also called aptrganga, literally "again-walker" (Icelandic: afturganga) is an undead creature from Norse mythology, a subset of Germanic mythology. The Old Norse meaning of the word is a revenant. "The will appears to be strong, strong enough to draw the hugr [animate will] back to one's body.

These reanimated individuals were known as draugar. However, though the dead might live again, they could also die again. Draugar live in their graves, often guarding treasure buried with them in their burial mound. A cognate is Old English: dréag "apparition, ghost".[2] Irish: dréag or driug, meaning "portent, meteor", is borrowed from either Old English or the Old Norse.[3] Traits[edit] The draugr's victims were not limited to trespassers in its howe.

Almas (cryptozoology) The Almas (Mongolian: Алмас/Almas, Bulgarian: Алмас, Chechen: Алмазы, Turkish: Albıs), Mongolian for "wild man", is a purported hominid cryptozoological species reputed to inhabit the Caucasus and Pamir Mountains of central Asia, and the Altai Mountains of southern Mongolia.[1] The creature is not currently recognized or cataloged by science.

Furthermore, scientists generally reject the possibility that such mega-fauna cryptids exist, because of the improbably large numbers necessary to maintain a breeding population,[2] and because climate and food supply issues make their survival in reported habitats unlikely.[3] Almas is a singular word in Mongolian; the properly formed Turkic plural would be 'almaslar'.[4] As is typical of similar legendary creatures throughout Central Asia, Russia, Pakistan and the Caucasus, the Almas is generally considered to be more akin to "wild people" in appearance and habits than to apes (in contrast to the Yeti of the Himalayas).

Tjutjuna Notes. List of legendary creatures. This is a list of legendary creatures from various historical mythologies.

Entries include species of legendary creature and unique creatures, but not individuals of a particular species. A[edit] B[edit] C[edit] D[edit] E[edit] Family tree of the Greek gods. Family tree of gods, goddesses and other divine figures from Ancient Greek mythology and Ancient Greek religion The following is a family tree of gods, goddesses and many other divine and semi-divine figures from Ancient Greek mythology and Ancient Greek religion.

(The tree does not include creatures; for these, see List of Greek mythological creatures.) Key: The essential Olympians' names are given in bold font. Key: The original 12 Titans' names have a greenish background. See also List of Greek mythological figures Notes References. Glámr. Glámr The following story is found in the Gretla, an Icelandic Saga, composed in the thirteenth century, or that comes to us in the form then given to it; but it is a redaction of a Saga of much earlier date.

Most of it is thoroughly historical, and its statements are corroborated by other Sagas. The following incident was introduced to account for the fact that the outlaw Gretter would run any risk rather than spend the long winter nights alone in the dark. At the beginning of the eleventh century there stood, a little way up the Valley of Shadows in the north of Iceland, a small farm, occupied by a worthy bonder, named Thorhall, and his wife. The farmer was not exactly a chieftain, but he was well enough connected to be considered respectable; to back up his gentility he possessed numerous flocks of sheep and a goodly drove of oxen. “I do not care about his wits so long as he can look after sheep,” answered Thorhall. “You may rely on his being able to do that,” said Skapti. “Pshaw! Zombie. Zombies have a complex literary heritage, with antecedents ranging from Richard Matheson and H.

P. Lovecraft to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein drawing on European folklore of the undead. George A. Werewolf.