How One Obscure Word Captures Urban China’s Unhappiness. Over the past few months, Chinese people from all walks of life, be they software developers, stay-at-home moms, or elite university students, have all discovered their daily lives can be accurately described by the same once-arcane academic term: involution.

Originally used by anthropologists to describe self-perpetuating processes that keep agrarian societies from progressing, involution has become a shorthand used by Chinese urbanites to describe the ills of their modern lives: Parents feel intense pressure to provide their children with the very best; children must keep up in the educational rat race; office workers have to clock in a grinding number of hours. Involution can be understood as the opposite of evolution. The Chinese word, neijuan, is made up of the characters for ‘inside’ and ‘rolling,’ and is more intuitively understood as something that spirals in on itself, a process that traps participants who know they won’t benefit from it.

Later, scholar Philip C. The Case for an Artistic Revival of Rural China. After four decades of rapid economic expansion, China’s cities are among the world’s biggest, most modern, and most developed.

But the benefits of this urban boom have been slow to trickle out to the country’s vast rural hinterland, where hundreds of millions of Chinese face a choice between scraping by in their economically backward hometowns or trying to build a better life for themselves in the city. The government is attempting to address the yawning rural-urban wealth gap and related migrant outflow through a variety of policies and programs, including poverty alleviation grants and renovating impoverished villages into tourism sites.

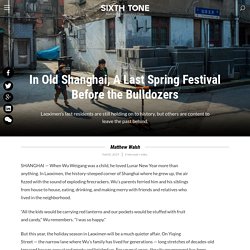

I believe there’s another way. Over the past decade, I’ve helped locals in two disparate villages — one northern, one southern — to revitalize their homes through engagement with the arts. Qu Yan introduces his work in Qingtian Village. The first biennial Heshun International Art Festival took place in 2011. In Old Shanghai, A Last Spring Festival Before the Bulldozers. SHANGHAI — When Wu Weigang was a child, he loved Lunar New Year more than anything.

In Laoximen, the history-steeped corner of Shanghai where he grew up, the air fizzed with the sound of exploding firecrackers. Wu’s parents ferried him and his siblings from house to house, eating, drinking, and making merry with friends and relatives who lived in the neighborhood. “All the kids would be carrying red lanterns and our pockets would be stuffed with fruit and candy,” Wu remembers. “I was so happy.” But this year, the holiday season in Laoximen will be a much quieter affair. Wu Weigang is one of the few remaining residents of Laoximen, a historic neighborhood that is undergoing demolition. In return for razing their former homes, officials are offering residents alternative housing or monetary compensation.

Laoximen is far from the first tract of Shanghai — or urban China — to fall foul of the government’s bulldozers. Why so glum, China? - Chaguan. China’s Ghost Towns Haunt Its Economy. China's Instant Cities. At 2:30 in the afternoon, the bosses began designing the factory.

The three-story building they had rented was perfectly empty: white walls, bare floors, a front door without a lock. You could come or go; everything in the Lishui Economic Development Zone shared that openness. Neighboring buildings were also empty shells, and they flanked a dirt road that pointed toward an unfinished highway. Blank silver billboards reflected the sky, advertising nothing but late October sunlight. Wang Aiguo and Gao Xiaomeng had driven the 80 miles (130 kilometers) from Wenzhou, a city on China's southeastern coast. On the first floor, we were joined by a contractor and his assistant.

How Class in China Became Politically Incorrect - BLARB. By Louisa Lim Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of China Blog pieces by Louisa Lim, building off episodes of the Little Red Podcast, an excellent new podcast that is hosted by Graeme Smith in collaboration with Louisa and distributed by ANU’s Chinoiresie.

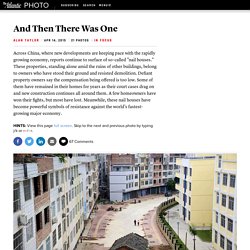

This post is based on Episode 11: “Class: The New Dirty Word”—JW “Never forget class struggle!” Was Chairman Mao’s exhortation to the Chinese people. The phrase was daubed on village walls, stenciled on drinking mugs, even painted on toilets around the country. Cookies are Not Accepted - New York Times. China's nail houses: the homeowners who refuse to make way – in pictures. China's 'nail houses': The homeowners who refused to budge. And Then There Was One. Across China, where new developments are keeping pace with the rapidly growing economy, reports continue to surface of so-called "nail houses.

" These properties, standing alone amid the ruins of other buildings, belong to owners who have stood their ground and resisted demolition. Defiant property owners say the compensation being offered is too low. Some of them have remained in their homes for years as their court cases drag on and new construction continues all around them. A few homeowners have won their fights, but most have lost. Meanwhile, these nail houses have become powerful symbols of resistance against the world's fastest-growing major economy.

Read more Hints:View this page full screen.