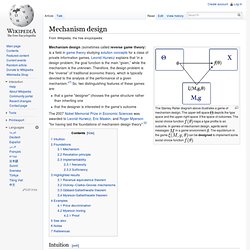

Elections and Strategic Voting. Mechanism design. The Stanley Reiter diagram above illustrates a game of mechanism design.

The upper-left space depicts the type space and the upper-right space X the space of outcomes. What is Mechanism Design? Two children are squabbling over how to divide a pie.

We need a method to divide the pie fairly. Parents will already know one answer—one child cuts and the second child chooses. Nirvana fallacy. The nirvana fallacy is the informal fallacy of comparing actual things with unrealistic, idealized alternatives.

It can also refer to the tendency to assume that there is a perfect solution to a particular problem. A closely related concept is the perfect solution fallacy. By creating a false dichotomy that presents one option which is obviously advantageous—while at the same time being completely implausible—a person using the nirvana fallacy can attack any opposing idea because it is imperfect. Under this fallacy, the choice is not between real world solutions; it is, rather, a choice between one realistic achievable possibility and another improbable solution that could in some way be better. History[edit] The nirvana fallacy was given its name by economist Harold Demsetz in 1969,[1][2] who said:[3] The view that now pervades much public policy economics implicitly presents the relevant choice as between an ideal norm and an existing 'imperfect' institutional arrangement.

Economic calculation problem. Mises argued in "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth" that the pricing systems in socialist economies were necessarily deficient because if a public entity owned all the means of production, no rational prices could be obtained for capital goods as they were merely internal transfers of goods and not "objects of exchange," unlike final goods.

Therefore, they were unpriced and hence the system would be necessarily irrational, as the central planners would not know how to allocate the available resources efficiently.[1] He wrote "...that rational economic activity is impossible in a socialist commonwealth. "[1] Mises developed his critique of socialism more completely in his 1922 book Socialism, an Economic and Sociological Analysis, arguing that the market price system is an expression of praxeology and can not be replicated by any form of bureaucracy. Theory[edit] Comparing heterogeneous goods[edit] Relating utility to capital and consumption goods[edit] Incentive compatibility. In mechanism design, a process is incentive-compatible if all of the participants fare best when they truthfully reveal any private information asked for by the mechanism.[1] As an illustration, voting systems which create incentives to vote dishonestly lack the property of incentive compatibility.

In the absence of dummy bidders, collusion, incomplete information, or other factors which interfere with process efficiency, a second price auction is an example of a mechanism that is incentive compatible. There are different degrees of incentive-compatibility: in some games, truth-telling can be a dominant strategy. A weaker notion is that truth-telling is a Bayes-Nash equilibrium: it is best for each participant to tell the truth, provided that others are also doing so. The term has also been used in economics research.[2] See also[edit] References[edit] Tactical voting. In voting systems, tactical voting (or strategic voting or sophisticated voting or insincere voting) occurs, in elections with more than two candidates, when a voter supports a candidate other than his or her sincere preference in order to prevent an undesirable outcome.[1] It has been shown by the Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem that, if a voting method for choosing one of several options is completely strategy-free, then it must be either dictatorial or nondeterministic (that is, might not select the same outcome every time it is applied to the same set of voter preferences).

For instance, the random ballot voting method, which randomly selects the ballot of a single voter and uses this to determine the outcome, is strategy-free, but may result in different choices being selected if applied multiple times to the same set of ballots. The Illusion of Certainty: Risk, Probability, and Chance. Stuff happens.

The weather forecast says it’s sunny, but you just got drenched. You got a flu shot—but you’re sick in bed with the flu. Your best friend from Boston met your other best friend from San Francisco. Coincidentally.