Victor Kandinsky Victor Khrisanfovich Kandinsky (Russian: Виктор Хрисанфович Кандинский) (April 6, 1849, Byankino, Nerchinsky District, Siberia – July 3, 1889, Saint Petersburg) was a Russian psychiatrist, and was 2nd cousin to famed artist Wassily Kandinsky.[1] He was born in Siberia into a large family of extremely wealthy businessmen.[2] Victor Kandinsky was one of the famous figures in Russian psychiatry and most notable for his contributions to the understanding of hallucinations.[3] Biography[edit] He graduated from Moscow Imperial University Medical School in 1872 and started to work as a general practitioner in one of the hospitals in Moscow.[4] In 1878 he married his medical nurse Elizaveta Karlovna Freimut (Russian: Елизавета Карловна Фреймут).[4] In October 1878, Victor again entered a psychiatric hospital. In 1881, he moved to Saint Petersburg.[4] Kandinsky was a mental health worker employed by the Psychiatric Hospital of St. Kandinsky joined the St. Scientific contribution[edit] Works[edit]

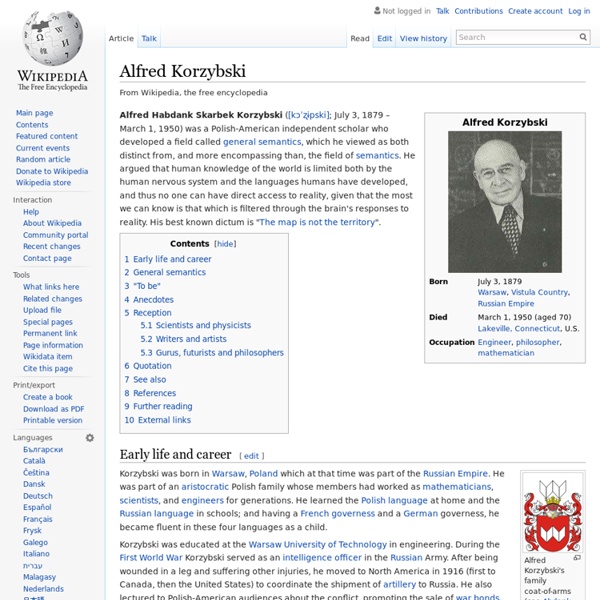

TopLinked.com (Open Networkers) Group News General semantics General semantics is a program begun in the 1920s that seeks to regulate the evaluative operations performed in the human brain. After partial launches under the names "human engineering" and "humanology,"[1] Polish-American originator Alfred Korzybski[2] (1879–1950) fully launched the program as "general semantics" in 1933 with the publication of Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. General semantics should not be confused with generalized semantics (a branch of linguistics). Misunderstandings traceable to the discipline's name have greatly complicated the program's history and development.[3] The sourcebook for general semantics, Science and Sanity, presents general semantics as both a theoretical and a practical system whose adoption can reliably alter human behavior in the direction of greater sanity. Its author asserted that general semantics training could eventually unify people and nations. Overview[edit] Extensional devices[edit]

The Institute of General Semantics Does Depression Help Us Think Better? | Wired Science Why do people get depressed? At first glance, the answer seems obvious: the mind, like the flesh, is prone to malfunction. Once that malfunction happens — perhaps it’s an errant gene triggering a shortage of some happy chemical — we sink into a emotional stupor and need medical treatment. But this pat explanation obscures a lingering paradox of depression, which is that the mental illness is extremely common. In recent years, a small cadre of researchers has begun exploring this apparent paradox, trying to understand why states of such extreme sadness are so widespread. Thomson and Andrews wondered if, just maybe, rumination wasn’t all bad. Imagine, for instance, a depression triggered by a bitter divorce. In other words, Thomson and Andrews imagined depression as a way of forcing the mind to focus on its problems. It’s an intriguing hypothesis (which is why I wanted to write about it), but the evidence for this “analytical rumination” theory is mostly speculative and indirect.

Nikolai Berdyaev Berdyaev's grave, Clamart (France). Nikolai Alexandrovich Berdyaev (/bərˈdjɑːjɛf, -jɛv/;[1] Russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Бердя́ев; March 18 [O.S. March 6] 1874 – March 24, 1948) was a Russian political and also Christian religious philosopher who emphasized the existential spiritual significance of human freedom and the human person. Alternate historical spellings of his name in English include "Berdiaev" and "Berdiaeff", and of his given name as "Nicolas" and "Nicholas". Biography[edit] Nikolai Berdyaev was born at Obukhiv,[2] Kiev Governorate in 1874, in an aristocratic military family.[3] His father, Alexander Mikhailovich Berdyaev, came from a long line of Kiev and Kharkiv nobility. Greatly influenced by Voltaire, his father was an educated man that considered himself a freethinker and expressed great skepticism towards religion. Berdyaev decided on an intellectual career and entered the Kiev University in 1894. In 1904, he married Lydia Yudifovna Trusheff. Philosophy[edit] Sources

Nelson Berry Subliminal Messages Video Blog Gouverner par le chaos Un article de Wikipédia, l'encyclopédie libre. Gouverner par le chaos - Ingénierie sociale et mondialisation est un ouvrage collectif et anonyme, inspiré par les publications de Tiqqun et du Comité invisible (auteur de L'insurrection qui vient), ainsi que par l’analyse des méthodes de contrôle social déployées par le pouvoir politique lors de l’affaire de Tarnac en 2008-2009. Remarqué par le Centre d’analyse stratégique du gouvernement français[1], cet essai est sorti chez Max Milo Éditions en mai 2010[2]. Avant cette publication dans une version augmentée, revue et corrigée, le texte avait déjà été diffusé sur Internet en fichier PDF dans un état que l’on peut qualifier de « brouillon avancé ». Le titre en était Ingénierie sociale et mondialisation, signé « Comité invisible ». Résumé[modifier | modifier le code] Références[modifier | modifier le code] Voir aussi[modifier | modifier le code] Articles connexes[modifier | modifier le code] Liens externes[modifier | modifier le code]

Off the Map: Notes from the Territory | A Blog about General Semantics | by Ben Hauck I admit: I’ve had considerable difficulty embracing general semantics as what some call “a system.” The difficulty stems from not being able to point at a system to know what the word “system” represents. However, I was watching the documentary Pina last night and it got me thinking about what a system might actually constitute. In the documentary about acclaimed dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch, you have in Pina someone with a distinctive view of movement and dance and what it should accomplish. And you have in Pina a leader whom others adored and followed. The leader-follower aspect of the Pina dynamic is not the interesting point but the supplemental point: That she had followers implies to a particular degree that she had an appreciable perspective. What makes up a perspective? If I look at you and say, “You are a woman,” I have thus framed you as “a woman.” Now, I’m not a huge fan of the word “frame” but that hopefully got you to understand my point. Leave a Comment (1 So Far)

Grand Theft Attention: video games and the brain Having recently come off a Red Dead Redemption jag, I decided, as an act of penance, to review the latest studies on the cognitive effects of video games. Because videogaming has become such a popular pastime so quickly, it has, like television before it, become a focus of psychological and neuroscientific experiments. The research has, on balance, tempered fears that video games would turn players into boggle-eyed, bloody-minded droogs intent on ultraviolence. The evidence suggests that spending a lot of time playing action games – the ones in which you run around killing things before they kill you (there are lots of variations on that theme) – actually improves certain cognitive functions, such as hand-eye coordination and visual acuity, and can speed up reaction times. But these studies have also come to be interpreted in broader terms. If only it were so. Recent studies back up this point. In a 2010 paper published in the journal Pediatrics, Edward L.

Nicolás Gómez Dávila We ask you, humbly, to help. Hi reader in Canada, it seems you use Wikipedia a lot; that's great! It's a little awkward to ask, but this Wednesday we need your help. We’re not salespeople. We’re librarians, archivists, and information junkies. We depend on donations averaging $15, but fewer than 1% of readers give. Maybe later Thank you! Close Nicolás Gómez Dávila (18 May 1913 – 17 May 1994) was a prominent Colombian writer and champion of reactionary social political theory. Gómez Dávila's fame began to spread only in the last few years before his death, particularly by way of German translations of his works. Biography[edit] In 1954, Gómez Dávila's first volume of works was published by his brother, a compilation of notes and aphorisms under the title Notas I – the second volume of which never appeared. Gómez Dávila discussed a vast range of topics, philosophical and theological questions, problems of literature, art, and aesthetics, philosophy of history and the writing of history.