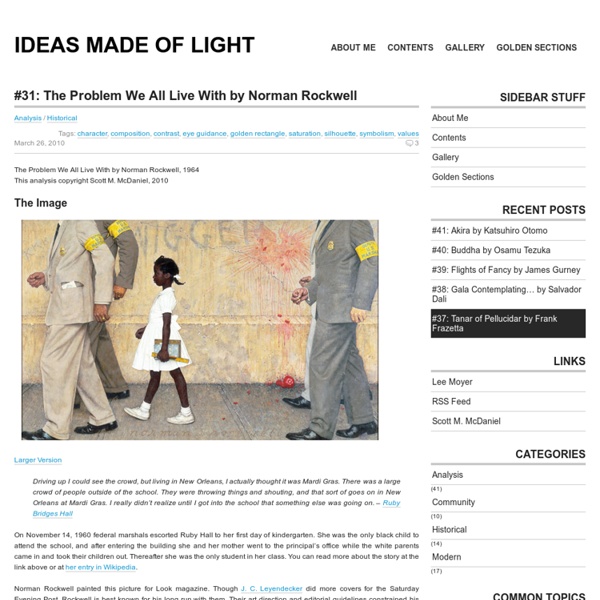

“Rockwell & Race”1963-1968 | The Pop History Dig Norman Rockwell’s painting of six year-old Ruby Bridges being escorted into a New Orleans school in 1960 was printed inside the January 14, 1964 edition of Look magazine. Click for art print. In June 2011 at the White House, Norman Rockwell’s 1963 painting, The Problem We All Live With, depicting a famous school desegregation scene in New Orleans, began a period of prominent public display with the support of President Obama. The White House exhibition of Rockwell’s piece, which ran most of 2011, drew national attention to an iconic moment in America’s troubled civil rights history. Rockwell’s painting focuses on an historic 1960 school integration episode when six year-old Ruby Bridges had to be escorted by federal marshals past jeering mobs to insure her safe enrollment at the William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans. Norman Rockwell at work, mid-career. Norman Rockwell, circa 1940s. Norman Rockwell Civil Rights Subjects Cover Art, 1950s Click to read at PBS.org. Cover Art ( cont’d)

Response to Segregation All images except those of the Manassas Industrial School are from the Library of Congress. Manassas Industrial School photos courtesy the Manassas Museum System, Manassas, Virginia. Some photos been edited or resized for this page. Black history in the US From MLK to ObamaUne séquence complète niveau 3ème proposée par Catherine Court-Maurice (Collège Le Chapitre) file_download Télécharger la séquence Black history Month (Time for Kids)Dossier très complet conçu pour de jeunes américains pour Black history month en février : Then and Now : timeline The fight for rights : texte et jeu Now hear this : discours de MLK, JFK et Lyndon Johnson The arts Infographie : From slavery to ObamaLes dates les plus marquantes (utilisé dans le cadre d’une étude du tableau The Problem We All Live With, de Norman Rockwell).Infographie réalisée à l’aide de la version gratuite d’Easel-ly. African American OdysseyDossier de la Bibliothèque du Congrès InfopleaseNombreuses ressources Biography.comNombreuses biographies de personnes ayant marqué l’histoire des noirs américains. Discovery school Un dossier très complet : The Ku Klux KlanPage de ressources A few Civil Rights activists Voir également : Dates Martin Luther King Day ( the third Monday of January)_

Let's Celebrate! - ESL-EFL task-based lesson plan by Mrs Recht's Virtual Classroom ☆☆☆☆ Have your students learn about British and American festivals! ☆☆☆☆ Here is a complete set of 10 worksheets to have your beginners students learn about British and American festivals, from reading a riddle to writing one, from watching a video to making one themselves. Content: ❑ Anticipation ❑ Reading and decoding a riddle ❑ Writing a riddle ❑ Watching a video (link on the worksheet) and taking notes ❑ Researching a celebration on a website (link on the worksheet) ❑ Preparing the script of the video ❑ Creating a video using Animoto (free education account) ☺If you want to see an example of the videos produced, here is a video made by one of my students ☞ Most cliparts come from Sarah Pecorino Illustration To contact me:@My Blog@ Facebook Page@ Pinterest@ Twitter ☺ How to get TPT credit to use on future purchases: → Please go to your My Purchases page (you may need to login). Terms of Use and Copyrights Policy

Ruby Bridges Un article de Wikipédia, l'encyclopédie libre. Pour les articles homonymes, voir Bridges. Ruby Bridges en 2010. Ruby Bridges Hall, née le 8 septembre 1954 à Tylertown au Mississippi, est une femme américaine connue pour être la première enfant de couleur à intégrer une école pour enfants blancs. Elle déménagea avec ses parents à La Nouvelle-Orléans, en Louisiane, à l'âge de six ans, en 1960. À cette date, ses parents répondirent à un appel du NAACP et acceptèrent que leur fille participe à l'intégration dans le nouveau système scolaire mis en place à La Nouvelle-Orléans. À cause de l'opposition des blancs à intégrer les noirs, elle eut besoin de protection pour entrer à l'école. mais, les officiers de police locaux et de l'État refusant de la protéger, elle fut accompagnée par des "marshall" fédéraux. Son premier jour d'école, le 12 novembre 1960, a été commémoré par Norman Rockwell dans un tableau intitulé The Problem We All Live With (Le problème avec lequel nous vivons tous).

The Problem We All Live With Un article de Wikipédia, l'encyclopédie libre. Description[modifier | modifier le code] Notes et références[modifier | modifier le code] ↑ (fr) « The Problem we All Live With » [archive], sur Académie de Toulouse (consulté le 26 mars 2014).↑ a et b (en) « The Problem We All Live With, Norman Rockwell, 1963. Oil on canvas, 36" x 58". Illustration for "Look," January 14, 1964. Voir aussi[modifier | modifier le code] Articles connexes[modifier | modifier le code] Liens externes[modifier | modifier le code] (en) Commentaires de Ruby Bridges et Barack Obama, suite à leur examen conjoint du tableau The Problem We All Live With dans l'aile Ouest de la Maison-Blanche, sur youtube.com (consulté le 26 mars 2014).

Dress for the Occasion | National Museum of African American History and Culture On the other hand, the president was hesitant to employ federal authority in defiance of the tradition of local control over law enforcement and education. He knew state and local leaders across the South would be horrified at this use of federal power, even if it was intended to support the rule of law. As the president of the Little Rock Chamber of Commerce put it, “. . . we hadn’t had federal troops since [18] ’67! That was so shocking that we didn’t know whether we should support the government or not” (Jacoway, Turn Away Thy Son). Eisenhower’s decision established a new precedent. Eisenhower’s reluctant use of federal authority in a civil rights matter in Little Rock in 1957 was just the beginning. Carlotta Walls and her fellow African American students wanted a quality education. Written by William Pretzer, Senior History Curator

4 février 1913 : naissance de Rosa Parks « la femme qui s'est tenue debout en restant assise » Les combats les plus emblématiques et les plus nobles naissent parfois d’événements désespérément quotidiens. Comme en ce 1er décembre 1955 dans l’État américain de l’Alabama. Ce jour-là, à Montgomery, Rosa Parks, une couturière noire de 42 ans, ne pouvait imaginer en montant dans le bus conduit par James Blake, que son refus de céder sa place à un passager blanc, allait changer son destin et contribuer à modifier la société américaine en profondeur. Considérée comme la mère du Mouvement des droits civiques, cette figure emblématique de la lutte contre la ségrégation raciale aux Etats-Unis travaillera toute sa vie pour l’égalité des droits. « D’abord, j’avais travaillé dur toute la journée. Peu après Martin Luther King lance une campagne de boycott contre la compagnie de bus. Finalement, le 13 novembre 1956, la Cour Suprême des Etats-Unis interdit la ségrégation raciale dans les bus, faisant de Rosa Parks une héroïne.

Free service to Convert & Download videos from Twitch, AnimeToon, LiveLeak, Facebook, VK, SoundCloud mp3, Putlocker, Vimeo and more... 5 Good Reasons why our users love TubeOffline:1. It's Free, Fast & Easy to use! 2. Convert videos to MP4/FLV/AVI format without any Signup or Software installation! 3. What is TubeOffline? Choose a Video Converter from the below list to convert & download a video. >> If your favorite video site is not listed, let us know, we will try to add it

Women Make History: An Untold Story of the Civil Rights Movement | Civil Rights Teaching Women Make History presents the important and extensive role of women in social justice movements. In this 45- to 90-minute lesson, participants take on the identity of one activist and interview at least six more. This lesson has been used successfully in middle and high school classes and in teacher workshops. Introduction One of the least recognized stories of the Civil Rights Movement is the role of women. This is true despite the fact that women were responsible for many of the achievements of the Movement. Teachers may use this activity to introduce students to many of the women involved in the Civil Rights Movement and related movements for social justice — women whose lives and legacies transformed our understanding of leadership and democracy. This activity is useful as preparation for a larger study of women in the Movement or of the Civil Rights Movement in general. Materials and Preparation Handout No. 2: What’s My Name? Procedures 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

FOOD AND WASTE/WAIST - My schoolbag To celebrate World Food Day, here are key ways of promoting more sustainable food systems from building grain reserves to taxing pollution worldfooddayusa.org World Food Day celebrates the creation of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) on October 16, 1945 in Quebec, Canada. First established in 1979, World Food Day has since then been observed in almost every country by millions of people. In North America, grassroots events and public awareness campaigns engage diverse audiences in action against hunger. Each year, advocates come together to raise awareness and engage Americans and Canadians in the movement to end hunger. BBC World Class Debate on World Food Day : videos Un site éducatif avec scénario catastrophe, vidéos et scripts; la démarche est expliquée dans les "webzines" Vidéo de présentation: climate change webzine pdf Food riots webzine pdf Another educational Site : Do One Thing For a Better World

Teaching about 1963: Civil Rights Movement History | Civil Rights Teaching The year 1963 was pivotal to the modern Civil Rights Movement. It is often recalled as the year of the March on Washington, but much more transpired. It was a year dedicated to direct action and voter registration and punctuated by moments of political theater and acts of violence. To support teaching about 1963 events, we describe here some of the key events and milestones in the Movement. Gloria Richardson facing off the National Guard, Cambridge, Maryland, May 1964. In 1963 in Baltimore, students from Morgan State and Howard universities successfully joined forces, filling the jails and forcing the hands of city officials, who after only one week of intense direct action agreed to end segregation of Northwood Theatre. Seeking desegregation of public facilities, representation in government, and fair employment, Movement workers in Durham, NC, Jackson, MS, Greensboro, NC, Danville, VA, St. The Children’s Crusade (Birmingham, AL) William Lewis Moore. Following Gov. John F.