Prosecutor in Aaron Swartz 'hacking' case comes under fire | Politics and Law A politically ambitious Justice Department official who oversaw the criminal case against Aaron Swartz has come under fire for alleged prosecutorial abuses that led the 26-year-old online activist to take his own life . Carmen Ortiz, 57, the U.S. attorney for Massachusetts who was selected by President Obama, compared the online activist -- accused of downloading a large number of academic papers -- to a common criminal in a 2011 press release. "Stealing is stealing whether you use a computer command or a crowbar," Ortiz said at the time. Last fall, her office slapped Swartz with 10 additional charges that carried a maximum penalty of 50 years in prison. "He was killed by the government," Swartz's father, Robert, said at his son's funeral in Highland Park, Ill., today, according to a report in the Chicago Sun Times. Last Wednesday, less than three months before the criminal trial was set to begin, Ortiz's office formally rejected a deal that would have kept Swartz out of prison. Rep.

Barrett Brown He has spent over a year in FCI Seagoville federal prison and at one time faced over a hundred more as he awaited trial on an assortment of seventeen charges filed in three indictments that include sharing an HTTP link to information publicly released during the 2012 Stratfor email leak, and several counts of conspiring to publicize restricted information about an FBI agent.[3][4][5][6] Between September 2013 and April 2014 he was held under an agreed gag order prohibiting him from discussing his case with the media.[3][7] Early life and education[edit] He attended the private Episcopal School of Dallas for high school but dropped out after his sophomore year. That summer, in 1998, he interned at the Met, an alternative weekly, and spent his would-be junior year unschooling in Tanzania with his father, who was trying to start a hardwood-harvesting business. While there Brown completed high school online through Texas Tech, earning college credit. Journalism[edit] Arrest and trial[edit]

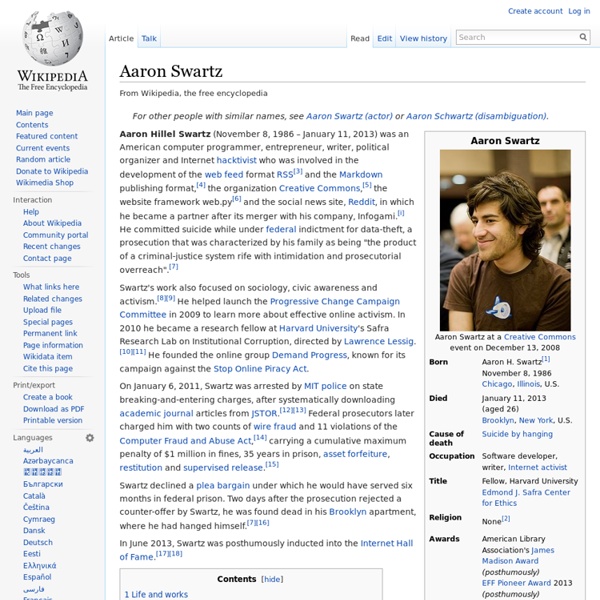

The Internet’s Own Boy: Film on Aaron Swartz Captures Late Activist’s Struggle for Online Freedom This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form. AMY GOODMAN: We’re broadcasting from Park City TV in Utah, home of the Sundance Film Festival, the largest festival for independent cinema in the United States. This is our fifth year covering some of the films here, and the people and topics they explore. Today, we spend the hour with the people involved in an incredible documentary that just had its world premiere here yesterday. AARON SWARTZ: I mean, I, you know, feel very strongly that it’s not enough to just live in the world as it is, to just kind of take what you’re given and, you know, follow the things that adults told you to do and that your parents told you to do and that society tells you to do. AMY GOODMAN: That was Aaron Swartz in his early twenties. In 2010, Aaron Swartz became a fellow at Harvard University’s Edmond J. Now, despite promises of reform, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act used to charge Swartz remains unchanged. REP. SEN. [break] ROBERT SWARTZ: Yeah.

After Aaron: how an antiquated law enables the government's war on hackers, activists, and you 18inShare Jump To Close Photo Credit: Daniel J. One day back in the early 1970s, two young computer miscreants named Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak exploited a hole in AT&T’s phone system to prank call the Pope. In July of 2011, Aaron Swartz was federally indicted for acts that in retrospect seem far more innocuous than those of Jobs and Wozniak. As security researcher and expert witness Alex Stamos explains, what Swartz did wasn't "hacking" — not even under the loosest interpretations. The CFAA may have been written with malicious computer break-ins in mind, but in reality it’s used to target an incredibly broad range of activities completely divorced from “hacking,” and Aaron Swartz is only the most recent example. The hook in Swartz's case had to do with something we should all be familiar with: Terms of Service. Video Review AT&T had known about the loophole, but ignored it. Again, none of this was “hacking” — anyone with an iPad serial number and enough smarts could have pulled it off.

How to Become Virtually Immortal It’s not enough that Internet companies have entered every corner of human existence—now, some are starting to cater to non-existence. In recent years, Google and Facebook have created systems to deal with death, such as suspending inactive accounts and allowing people to bequeath their data to a surviving friend or relative. The newest entry in the e-death industry is a small start-up called Eterni.me, which is taking end-of-life services to Asimovian extremes. Never has the cryonics movement, with its promise of reviving frozen bodies in the future, seemed so old-school. The company plans to store data from Facebook, Twitter, e-mail, photos, video, location information, and even Google Glass and Fitbit devices. The service’s defining feature is a 3-D digital avatar, designed to look and sound like you, whose job will be to emulate your personality and dish out bits of information to friends and family taken from a database of stored information. Illustration by Dadu Shin.

Internet Activist's Prosecutor Linked To Another Hacker's Death Murder in virtual reality should be illegal | Aeon Ideas You start by picking up the knife, or reaching for the neck of a broken-off bottle. Then comes the lunge and wrestle, the physical strain as your victim fights back, the desire to overpower him. You feel the density of his body against yours, the warmth of his blood. Now the victim is looking up at you, making eye contact in his final moments. Science-fiction writers have fantasised about virtual reality (VR) for decades. But this new form of entertainment is dangerous. Get Aeon straight to your inbox This is not the argument of a killjoy. So I understand the appeal of VR, and its potential to make a story all the more real for the viewer. The effects of all this gore are not clear-cut. The problem of what entertainment does to us isn’t new. Humans are embodied beings, which means that the way we think, feel, perceive and behave is bound up with the fact that we exist as part of and within our bodies. It’s a small step from here to truly inhabiting the body of another person in VR.

Tom Dolan, Husband Of Aaron Swartz's Prosecutor, Defends Her On Twitter When Internet activist Aaron Swartz was found dead in his Brooklyn apartment on Friday after an apparent suicide, friends, family and those who never knew him offered their condolences for the deceased 26-year-old. Even MIT, an institution that has been criticized for not doing enough to ease pressure from federal prosecutors who charged Swartz with allegedly stealing millions of online scholarly articles, said in a statement that "[w]ith this tragedy, his family and his friends suffered an inexpressible loss, and we offer our most profound condolences." But Tom Dolan, husband of U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz, took a different approach on Twitter that some are calling insensitive. Late Monday night, the former executive at IBM began tweeting in defense of his wife -- by criticizing Swartz's grieving family. @mkapor Truly incredible that in their own son's obit they blame others for his death and make no mention of the 6-month offer.— Tom Dolan (@tomjdolan) January 15, 2013 h/t @YourAnonNews.

40 Cool Inventions and Gadgets That Will Change Your Life | 2016 2016 has been an awesome year for new and innovative inventions that we are all sure to love, need, or simply must have. Some have been designed to save us time, some to save money, and some just do allow us to have more fun. The only question left for the world to answer is which one should be gotten first. Most of the innovative gadgets have been funded successfully on Indiegogo, Kickstarter and have been made available for public to buy. When I started researching for this post, I found several cool gadgets with the aim to transform your life in a number of ways but I found the following interesting and hopefully will add more in the future. 1. Last year, Tesla Motors released a new firmware update for the Model S which is freaking awesome. According to the studies, more advance technology will help to reduce accidents on roads. You can learn more about the Autopilot features on the official blog. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26.

Carmen Ortiz's Husband Criticizes Swartz Family For Suggesting Prosecution Of Their Son Contributed To His Suicide As we've stated over and over again, it's a bit simplistic to place the "blame" for Aaron Swartz's suicide on the federal prosecutors, led by US Attorney Carmen Ortiz and her assistant Stephen Heymann. It is still quite reasonable to question their activities, but suicide is a complex thing and going all the way there may be going too far. Still, you can understand why Swartz's family did, in fact, directly call out the US Attorneys given their hardline position on the case, and the stress that created for Swartz. Lots of reporters have been contacting Ortiz and Heymann and the US Attorneys' offices and have consistently been getting back a big fat "no comment." Some reporters are even upset that no one put President Obama on the spot concerning the Swartz suicide at Obama's recent press conference. However, some noticed that Ortiz's husband -- an IBM exec named Tom Dolan -- apparently felt no such restriction.

Science fact: Sci-fi inventions that became reality Image copyright Getty Images The story of a 14-year-old girl who won a landmark legal battle to be preserved cryogenically has many people wondering how such technology actually works - for many of us, it seems like something straight out of science fiction. But sci-fi has a long history of becoming science fact, as outlandish creations inspire real research. Remarkable realities Tractor beams In Star Wars, the unfortunate heroes are caught in a "tractor beam" that freezes their ship and pulls them towards the enemy. An Australian university can do the same thing - although its experiments with lasers could only manage to move a tiny object (one fifth of a millimetre) along about 20cm. Image copyright Asier Marzo/Bruce Drinkwater/Sriram Subramanian British researchers, meanwhile, have been experimenting with sound waves to shift objects through the air - and can just about manage objects the size of a pea at about 40cm away. The moon landing Image copyright Science Photo Library Energy weapons