Reviving the Working Class Without Building Walls Photo Can the government help ’s supporters? The political system is in shock over the insurrection of the white working class, which has flocked to Mr. Trump’s candidacy. On the wrong side of globalization and technological change, no longer at home in an increasingly multiethnic America, these voters have eagerly embraced his simple proposal to make things better: walls against the imports and the people they believe have robbed them of a shot at prosperity. That strategy, if it amounts to that, would visit a disaster of epic proportions upon the world economy. As Lawrence H. But the raw anxiety of his supporters remains unaddressed. It is not obvious how to restore the America Mr. Their economic discontent — born of the mismatch between expectations based on an earlier America, where plenty of blue-collar jobs offered a decent standard of living, and the more cutthroat reality they face today — can seem intractable, too. These proposals represent only a start.

This computer programmer solved gerrymandering in his spare time Yesterday, I asked readers how they felt about setting up independent commissions to handle redistricting in each state. Commenter Mitch Beales wrote: "It seems to me that an 'independent panel' is about as likely as politicians redistricting themselves out of office. This is the twenty-first century. How hard can it be to create an algorithm to draw legislative districts after each census?" Reader "BobMunck" agreed: "Why do people need to be involved in mapping the districts?" They're right. You can see for yourself how his boundaries look. Here's Maryland, currently the least-compact state in the nation: And here's North Carolina, the second-least compact: Huge differences, yes? Now, some argue that compactness isn't a very good measure of district quality. And therein lies the problem: You can define a "community of interest" pretty much however you want. Wonkbook newsletter Your daily policy cheat sheet from Wonkblog. Please provide a valid email address.

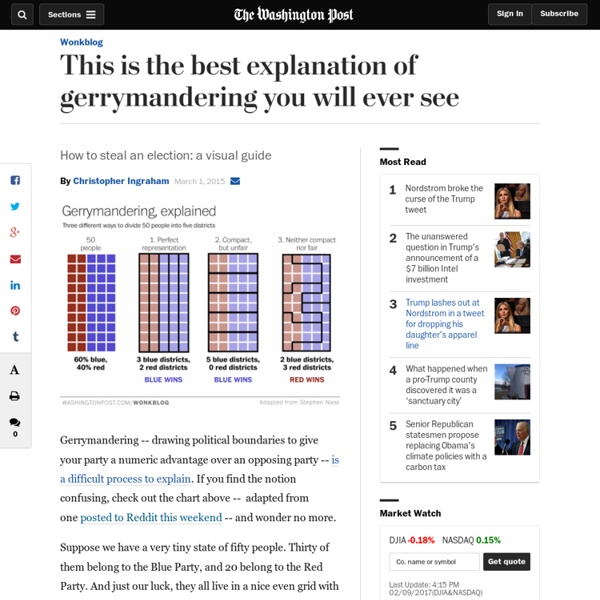

America’s most gerrymandered congressional districts Crimes against geography. This election year we can expect to hear a lot about Congressional district gerrymandering, which is when political parties redraw district boundaries to give themselves an electoral advantage. Gerrymandering is at least partly to blame for the lopsided Republican representation in the House. According to an analysis I did last year, the Democrats are under-represented by about 18 seats in the House, relative to their vote share in the 2012 election. The way Republicans pulled that off was to draw some really, really funky-looking Congressional districts. Contrary to one popular misconception about the practice, the point of gerrymandering isn't to draw yourself a collection of overwhelmingly safe seats. The process of re-drawing district lines to give an advantage to one party over another is called "gerrymandering". The process of re-drawing district lines to give an advantage to one party over another is called "gerrymandering". 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7.

From Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump: Watch how the Republican Party has shifted on immigration | US elections Donald Trump has gone from reality television star to frontrunner for the Republican presidential nomination because of one issue – immigration. His campaign has been defined by incendiary anti-immigration rhetoric and it has found support across America with Trump securing 46% of the delegates that have been on offer so far. The billionaire has publicly targeted Mexicans and Muslims; and while today might be a different world, the GOP stance on immigration has not always been as extreme. 36 years ago during a primary debate between then-Republican presidential candidates Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush in Houston, both championed immigrants living in the United States when faced with the question: “Do you think the children of illegal aliens should be allowed to attend Texas public schools for free, or do you think their parents should pay for their education?” “The answer to your question is much more fundamental than whether they attend Houston schools, it seems to me. Loaded: 0%

Voters Not Politicians The Electoral College Was Meant to Stop Men Like Trump From Being President Americans talk about democracy like it’s sacred. In public discourse, the more democratic American government is, the better. The people are supposed to rule. But that’s not the premise that underlies America’s political system. Most of the men who founded the United States feared unfettered majority rule. The framers constructed a system that had democratic features. The Bill of Rights is undemocratic. That’s the way the framers wanted it. Donald Trump was not elected on November 8. The Constitution says nothing about the people as a whole electing the president. This ambiguity about how to choose the electors was the result of a compromise. It is “desirable,” Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 68, “that the sense of the people should operate in the choice of” president. As Michael Signer explains, the framers were particularly afraid of the people choosing a demagogue. In truth, Americans are wedded less to democracy than to familiarity. This makes sense. Related Videos

The American Presidency Project Competitive Congressional Districts This is a proof-of-concept of an idea from Dr. Sam Wang at Princeton Election Consortium to create an app allowing people to enter an address and find nearby competitive Congressional Districts. Competitive districts, shaded in purple, are those defined as Tossup or Lean D or R, by the Cook Political Report. Click on a district for more information. Thanks to Stephen Wolf at Daily Kos Elections for an updated geographic file that incorporates 2015 Florida and Virginia redistricting. Updated Oct. 14. Enter Address, City or Zip Code Search Reset The Constitution lets the electoral college choose the winner. They should choose Clinton. Lawrence Lessig is a professor at Harvard Law School and the author of “Republic, Lost: Version 2.0.” In 2015, he was a candidate in the Democratic presidential primary. Conventional wisdom tells us that the electoral college requires that the person who lost the popular vote this year must nonetheless become our president. That view is an insult to our framers. It is compelled by nothing in our Constitution. It should be rejected by anyone with any understanding of our democratic traditions — most important, the electors themselves. The framers believed, as Alexander Hamilton put it, that “the sense of the people should operate in the choice of the [president].” Hillary Clinton spoke to supporters, Nov. 9, offering a message of thanks, apology and hope. Hillary Clinton spoke to supporters, Nov. 9, offering a message of thanks, apology and hope. [Don’t blame the electoral college. Many think we should abolish the electoral college. So, do the electors in 2016 have such a reason? opinions

'The country isn’t the earth beneath our feet, it’s the people' Similarly, I have vowed not to drink the raw alcohol of a passing enthusiasm to join patriotic acts in a frenzy. I would tolerate poor work rather than beat up the servants – the prospect of saying or doing something in a fit of anger makes both my mind and body shrink. I know Bimla is contemptuous of this disinclination – she considers it a form of mildness; she is angry with me today for the same reason, for she sees me refusing to do as I please with the war cry of “Vande Mataram” on my lips. That I have not joined in the worship of the goddess nation with a glass of alcohol in my hand has angered everyone. For I say that those who do not feel motivated to serve their country when they think of their nation as nothing but their nation and respect people as nothing but people, who need to be hypnotised with shrieking invocations to a mother or a deity, do not love their country so much as they love passion. We no longer feel strong once we set our mind free.

4/4/17: The Mathematics Behind Gerrymandering Quantifying Bizarreness Gerrymanderers rig maps by “packing” and “cracking” their opponents. In packing, you cram many of the opposing party’s supporters into a handful of districts, where they’ll win by a much larger margin than they need. In cracking, you spread your opponent’s remaining supporters across many districts, where they won’t muster enough votes to win. For instance, suppose you’re drawing a 10-district map for a state with 1,000 residents, who are divided evenly between Party A and Party B. Such gerrymanders are sometimes easy to spot: To pick up the right combination of voters, cartographers may design districts that meander bizarrely. Yet it’s one thing to say bizarre-looking districts are suspect, and another thing to say precisely what bizarre-looking means. The Supreme Court justices have “thrown up their hands,” Duchin said. The compactness problem will be a primary focus of the Tufts workshop. The Accidental Gerrymander Wasted Votes The Question of Intent