Lessons from Vincent Lingiari: a Voice is worth fighting for. Part 1 of nothing at all: A legislated First Nations Voice.

If the Morrison government legislates the Voice without constitutionally enshrining it, it will not only ignore the Uluru Statement and the unprecedented consensus that made it, it will also ignore our nation's history. It will be setting us up to fail, because we know that a First Nations Voice established by an act of parliament alone, not protected by the constitution will one day be diminished or repealed at the whim of a future parliament. This has been the fate of all national Indigenous representative bodies. Part 2 of nothing at all: Symbolic constitutional recognition. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people did not support symbolic constitutional recognition in 1999, and again dismissed it in 2017 in the regional constitutional dialogues.

Minister Wyatt has informed us that his government is walking away from the Uluru Statement, but we cannot let it. The Wave Hill walk-off is celebrated as a success. Australians Together. Today, Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody’s song is known across the nation, although fewer people know the story of the Gurindji strikers it tells of.

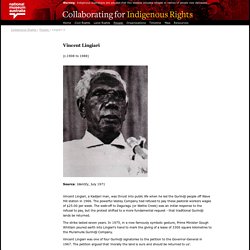

Lyrics Gather round people I'll tell you a story An eight-year-long story of power and pride 'Bout British Lord Vestey and Vincent Lingiarri They were opposite men on opposite sides Vestey was fat with money and muscle Beef was his business, broad was his door Vincent was lean and spoke very little He had no bank balance, hard dirt was his floor From little things big things grow Gurindji were working for nothing but rations. Vincent Lingiari. Vincent Lingiari (1919?

-1988), Aboriginal stockman and land rights leader, was born in 1919, according to government records, at Victoria River Gorge, Northern Territory, son of Gurindji parents. Both his mother and his father, also Vincent Lingiari, were employed on the 3500-sq. mile (9065 km²) Vestey-owned cattle station, Wave Hill, established in 1883 by Nathaniel Buchanan. Called Tommy Vincent by his employers, he received no formal education. Aged about 12 he was absorbed into the station work at the stock camps, where cattle from the 80,000 herd were mustered, branded and drafted into mobs of 1200 bullocks to be driven to meatworks at Port Darwin. Although Lingiari became a head stockman at Wave Hill, he initially received no cash payment. Right Wrongs – Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

The Wave Hill 'walk-off' - Fact sheet 224 – National Archives of Australia, Australian Government. Wave Hill Station is located approximately 600 kilometres south of Darwin in the Northern Territory.

Vesteys, a British pastoral company which ran the cattle station, employed local Aboriginal people, mostly Gurindji. Working and living conditions for Aboriginal people were very poor. The wages of Aboriginal workers generally were controlled and not equal to those paid to non-Aboriginal employees. An attempt to introduce equal wages for Aboriginal workers was made in 1965, but in March 1966 the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission decided to delay until 1968 the payment of award wages to male Aboriginal workers in the cattle industry. In August 1966, Vincent Lingiari, a Gurindji spokesman, led a walk-off of 200 Aboriginal stockmen, house servants, and their families from Wave Hill as a protest against the work and pay conditions. Collaborating for Indigenous Rights 1957-1973.

(c.1908 to 1988) Source: Identity, July 1971 Vincent Lingiari, a Kadijeri man, was thrust into public life when he led the Gurindji people off Wave Hill station in 1966.

The powerful Vestey Company had refused to pay these pastoral workers wages of $25.00 per week. The walk-off to Daguragu (or Wattie Creek) was an initial response to the refusal to pay, but the protest shifted to a more fundamental request - that traditional Gurindji lands be returned. The strike lasted seven years. Vincent Lingiari was one of four Gurindji signatories to the petition to the Governor-General in 1967. Lingiari continued to play a leadership role as the Gurindji people established this company on lands finally recognised as belonging to them. The Wave Hill walk-off: more than a wage dispute - History (6,10) 00:00:10:13REPORTER:Blackfella's country - until recently, few people realised that there might be such a thing.

The idea that the Aborigine might own some of the land he discovered 100,000 years ago is one of the rude awakenings for Australians in the 1960s.00:00:24:24MAN:(Plays didgeridoo)00:00:30:23REPORTER:And these are the people who brought about the awakening, the Gurindjis, the remnants of a once-magnificent tribe now dressed like Hollywood extras and set against a background of squalor. The Gurindjis are almost without exception stockmen. They first pricked the national conscience in 1966 when they went on strike at Wave Hill Station, 500 miles south of Darwin. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Land rights for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples refers to the ongoing struggle to gain legal and moral recognition of ownership of lands and waters they called home prior to colonisation of Australia in 1788.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ laws and customs and ways of knowing and being in the world are intimately connected to the land and waters. Connection to land is therefore essential to the continued cultural survival of Indigenous Australians as well as their economic and social development. Yirrkala bark petitions. Vincent Lingiari the leader - History (6)