David Brooks, Neuroendocrinologist. David Brooks, Neuroendocrinologist Having digested Leonard Sax on "the emerging science of sex differences", David Brooks has been continuing his education in neuroscience by reading Louann Brizendine's The Female Brain ("Is Chemistry Destiny?

" 9/17/2006): These sorts of stark sex differences were once highly controversial, and not fit for polite conversation. And some feminists still argue that talking about biological differences between the sexes is akin to talking about biological differences between the races. Two Myths and Three Facts About the Differences in Men and Women's Brains. MYTH 1 Women’s brains are more balanced "It is true that men use one side of their brain to listen while women use both sides," says the Suite 101 website with misplaced confidence. This is a variation of the popular idea found in many books and websites that men depend more than women on one hemisphere or the other for particular functions (especially language), and related to this, that women have a chunkier corpus callosum—the bridge of neurons that connects the two brain hemispheres. One source of the myth is a theory proposed by the late US neurologist Norman Geschwind and his collaborators in the 1980s, that higher testosterone levels in the womb mean the left hemisphere of male babies develops more slowly than females, and that it ends up more cramped.

But the Geschwind claim is not true: John Gilmore and his team scanned the brains of 74 newborns and found no evidence for smaller left hemispheres in male babies compared with females. Brain Stimulation Makes the 'Impossible Problem' Solvable. "The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify...into every corner of our mind.

" - John Maynard Keynes Try connecting all nine of these dots with just four straight lines without lifting your finger or retracing a line: Have difficulty? You're not alone. A century of psychological research shows that under laboratory conditions, the expected solution rate for this 'nine-dot' problem is 0 percent. Most people continue having difficulty solving the problem after given hints, extended time, and even 100 chances! Biologists locate brain's processing point for acoustic signals essential to human communication. In both animals and humans, vocal signals used for communication contain a wide array of different sounds that are determined by the vibrational frequencies of vocal cords.

For example, the pitch of someone's voice, and how it changes as they are speaking, depends on a complex series of varying frequencies. Knowing how the brain sorts out these different frequencies -- which are called frequency-modulated (FM) sweeps -- is believed to be essential to understanding many hearing-related behaviors, like speech. It "Rewires Your Brain?" Think Again.

It seems so archaic: I type with my fingers and I use my hands to drive.

Isn't there a better interface than the body? I want devices that can read my mind. It turns out that's not so far off. In a truly amazing line of research, it has been shown that implanting electrodes in the motor cortex of a non-human primates brain allows animals to control robotic arms without moving their bodies. ( Watch a video. ) All it takes is some training for the animals to learn to "think" the arm's actions. Just imagine the implications for people who are paralyzed. There are also non-invasive brain imaging techniques that allow people, even people who are completely paralyzed, to communicate simple ideas (e.g., answer yes/no questions) entirely with their brains. ( Read more .)

A better way to remember. Scientists and educators alike have long known that cramming is not an effective way to remember things.

With their latest findings, researchers at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute in Japan, studying eye movement response in trained mice, have elucidated the neurological mechanism explaining why this is so. Published in the Journal of Neuroscience, their results suggest that protein synthesis in the cerebellum plays a key role in memory consolidation, shedding light on the fundamental neurological processes governing how we remember. RSA Animate - The Divided Brain.

Making memories last: Prion-like protein plays key role in storing long-term memories. Memories in our brains are maintained by connections between neurons called "synapses.

" But how do these synapses stay strong and keep memories alive for decades? Neuroscientists at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research have discovered a major clue from a study in fruit flies: Hardy, self-copying clusters or oligomers of a synapse protein are an essential ingredient for the formation of long-term memory. The finding supports a surprising new theory about memory, and may have a profound impact on explaining other oligomer-linked functions and diseases in the brain, including Alzheimer's disease and prion diseases.

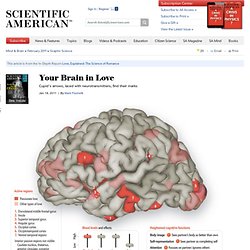

Your Brain in Love. Men and women can now thank a dozen brain regions for their romantic fervor.

Researchers have revealed the fonts of desire by comparing functional MRI studies of people who indicated they were experiencing passionate love, maternal love or unconditional love. Together, the regions release neurotransmitters and other chemicals in the brain and blood that prompt greater euphoric sensations such as attraction and pleasure. Conversely, psychiatrists might someday help individuals who become dangerously depressed after a heartbreak by adjusting those chemicals. Passion also heightens several cognitive functions, as the brain regions and chemicals surge. “It’s all about how that network interacts,” says Stephanie Ortigue, an assistant professor of psychology at Syracuse University, who led the study. Graphics by James W.