How online gamers are solving science's biggest problems. For all their virtual accomplishments, gamers aren't feted for their real-world usefulness.

But that perception might be about to change, thanks to a new wave of games that let players with little or no scientific knowledge tackle some of science's biggest problems. And gamers are already proving their worth. In 2011, people playing Foldit, an online puzzle game about protein folding, resolved the structure of an enzyme that causes an Aids-like disease in monkeys. Researchers had been working on the problem for 13 years. The gamers solved it in three weeks. A year later, people playing an astronomy game called Planet Hunters found a curious planet with four stars in its system, and to date, they've discovered 40 planets that could potentially support life, all of which had been previously missed by professional astronomers. On paper, gamers and scientists make a bizarre union.

The potential is huge. Phylo Make patterns and research diseases Foldit Make a shape and understand proteins. Playing 'serious games,' adults learn to solve thorny real-world problems. It is never easy for interest groups with conflicting views to resolve public policy disagreements involving complex scientific issues. To successfully formulate complex treaties, such as the recent Paris Climate Change Agreement, countries must find a way to meet the interests of almost 200 national representatives, while simultaneously getting the science right. Lowest common denominator political agreements that don’t actually solve the problem are useless. Similarly, within countries, national policymakers need to mesh the conflicting concerns of public officials, civil society organizations and business interests to set health and safety standards that work. To do this, they must bring everyone up to speed on the scientific and technical aspects of the problem they are addressing.

Merely wrangling a political agreement isn’t enough. Likewise, at the municipal level, communities are confronting issues such as the local public health risks of climate change.

Illustrated Guide to Participatory City Download version. Journal of the mental environment. Interviews on THE END OF PROTEST by Micah White — the end of protest: a new playbook for revolution. Rudyard: Micah White, welcome to The Next Debate podcast.

Micah: Thank you very much. I'm so glad to be here. Rudyard: Well, let's dive right in here, and have you unpack an interesting title for this book, The End of Protest and a New Playbook for Revolution. Those two ideas seem in conflict. What are you getting at? Micah: Well, the book basically comes out of this realisation that we've been having the largest and most frequent protests in human history, and yet these protests don't seem to be creating the social change that we desire. Rudyard: Let's go to the stagnation quandary first, because you're right, there are all kinds of reasons why we would expect people on the street…record levels of economic inequality across Europe, the United States, increasing dissatisfaction with political elite so, again, why the lack of the type of social ferment that we saw throughout the 20th Century? Micah: There are basically two factors that play against each other. Resources. Jacques-François Marchandise.

Chapter 1: Principles of Participation – The Participatory Museum. It’s 2004.

I’m in Chicago with my family, visiting a museum. We’re checking out the final exhibit—a comment station where visitors can make their own videos in response to the exhibition. I’m flipping through videos that visitors have made about freedom, and they are really, really bad. Method guide. Design Thinking and the Politics of Atrocity Prevention. Politics and design thinking: more in common than you think - Praxis. Last week, USIP’s Andrew Blum wrote a great piece (on Tom Murphy’s A View From The Cave) about the limitations of design thinking when it comes to politics.

Blum makes the solid point that design thinking works best when a certain amount of consensus exists around the problem that’s being addressed. For political issues, which are all about contested power and disagreements over values, such consensus is elusive. Design thinking has found its entry points into political issues with narrow targeting. Blum’s example is the Atrocity Prevention Challenge. It focuses on information-gathering as a way to prevent violence, while essentially ignoring (or making unstated assumptions about) how the gathered information actually translates to violence prevention. However, I think there’s hope. There are several natural overlaps between design thinking and political analysis. Chief among these overlaps is a human-centered approach.

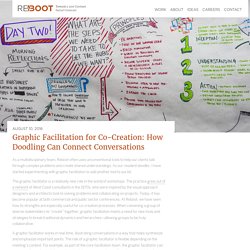

Graphic Facilitation for Co-Creation: How Doodling Can Connect Conversations - As a multidisciplinary team, Reboot often uses unconventional tools to help our clients talk through complex problems and create shared understandings.

Stanford Social Innovation Review. (Illustration by Darrel Rees) In recent years, the method of organizational change known as co-creation has spread rapidly in the business sector.

In a co-creation effort, multiple stakeholders come together to develop new practices that traditionally would have emerged only from a bureaucratic, top-down process (if, indeed, those practices would have emerged at all). Change, moreover, occurs not just at the level of an organization, but also across an entire value chain.