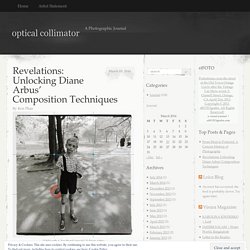

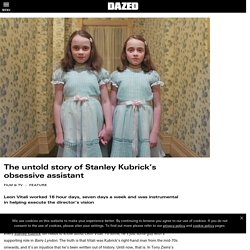

Revelations: Unlocking Diane Arbus’ Composition Techniques. “Child with A Toy Hand Grenade” © Diane Arbus As I was sitting in my living room flipping through the pages of Diane Arbus Revelations, I realized that all of her photographs shared the same visual element.

Not the perversity or the freakish that my mind continuously sipped at her photos throughout the years. It was the identical arrangement repeated to the same effect in all of her photographs. Most of her subjects were presented almost dead-center in the foreground, against a soft-focused background; the lens of her camera constantly focused on the subject’s eyes.

In each photograph, their eyes seemed to stare out with frozen dejection. The weirdness of Arbus’s photos had stimulated my curiosity since the mid 1990s, but it had never crossed my mind to study her life and photographs until I watched “Fur.”

Diane Arbus's New York. Following Arbus, many photographers turned ordinary people into art Humans of New York owes her a debt.

So do Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, Sally Mann, and—if you’re anything like us—at least 30 percent of the folks you follow on Instagram. We’re talking about Diane Arbus, the legendary photographer.Born Diane Nemerov in 1923, Arbus got her start running a commercial photography business with her husband, Allan Arbus. In 1956, she quit and took up street photography in earnest. She was 33. I really believe there are things which nobody would see unless I photographed them.Diane Arbus.

“Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer” In 1969, the Metropolitan Museum of Art agreed to buy three photographs by Diane Arbus, for seventy-five dollars each.

Wiser counsels prevailed, however, and a few months later the museum decided to take only two. Why splurge? The Museum of Modern Art was more daring; in 1964, it had acquired seven Arbus photos, including “Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C.” Not until the aftermath of Arbus’s death, however, in 1971, and the retrospective of her work at moma the following year, did public fascination start to seethe, swelling far beyond the bounds of her profession.

The swell has never slowed, and prices have followed suit. Diane Arbus: American portraits. Introduction | View of the world | Intention and effect | The aristocrats | The prints | Know life | Arbus legacy | Travelling venues and dates | Education Resource The prints Arbus stated that, for her, 'the subject of the picture is more important than the picture'.

There is no doubt that the emotional authenticity of what she photographed was of upmost importance. In keeping with this, she often undersold her skill as a photographer; she often complained of technical difficulties, and others frequently observed that she seemed weighed down by her equipment. Intimate-dark-and-compelling-the-photographs-of-diane-arbus-20180227-h0wpvp. The Transformative Nature of the Photographs of Diane Arbus. Exceeding the Frame: The Photography of Diane Arbus. Metaphors for vision overwhelm the English language.

"To see" is to know or to understand; "to envision" is to create or innovate; "to gaze" is to project desire, possess, and control; "to watch" is to study, examine, or take heed; "to witness" is to take part in history. Looking invokes embodied interest; glancing is unconscious; staring is deliberate and sometimes unsanctioned. Viewing proves dubious at best, especially when it comes to looking at other people, ourselves, and being looked at. Photography intensifies these metaphors for vision, turning human acts and appearances into images. Through various genres and conventions, photography frames human bodies for viewing and assigns meaning to them. The untold story of Stanley Kubrick’s obsessive assistant. Leon Vitali worked 16 hour days, seven days a week and was instrumental in helping execute the director’s vision Every Stanley Kubrick fan needs to know about Leon Vitali.

To some, he’s just some guy with a supporting role in Barry Lyndon. The truth is that Vitali was Kubrick’s right-hand man from the mid-70s onwards, and it’s an injustice that he’s been written out of history. Until now, that is. In Tony Zierra’s insightful, unexpectedly moving documentary Filmworker, we learn that Vitali abandoned a blossoming acting career in order to become Kubrick’s full-time personal assistant. But how did the pair hook up in a pre-LinkedIn era? Though we like to romanticise Kubrick as a one-man movie-making auteur, Vitali was an essential artistic collaborator, and Filmworker is a testament to the many underdogs of cinema whose stories are rarely told. Let’s face it, the duel scene in the barn is Barry Lyndon’s best moment. That said, there was one task Vitali wouldn’t do. How Diane Arbus went from a ‘freak show’ to a photographer who saw the ‘divineness in ordinary things’

Diane arbus: in the beginning Yale University Press 256 pp; $50.00 When the photographs of Diane Arbus began appearing in the 1960s, critics knew immediately what should be said about them.

Clearly, she was a clever intellectual exploiting the marginalized people she chose as her subjects. Odd looking and even grotesque men, women and children populated her pictures. She saw nudists, female impersonators, dwarfs and circus performers from a cool, cruel distance. An uncaring approach gave her pictures their special energy and gave Arbus a reputation for originality. That was Susan Sontag’s view. Full Exposure. Female impersonators, midgets, hermaphrodites, tattooed (all over) men, an albino sword swallower, a human pincushion, a Jewish giant: “Characters in a Fairy Tale for Grown Ups” is the way Diane Arbus once described her subjects—“people who appear like metaphors somewhere further out than we do,” she also said, “invented by belief.”

Yet Arbus could produce the same sense of dire enchantment in photographs of the most ordinary people: Fifth Avenue matrons, Coney Island bathers, even children. Other photographers focussed on the passing human comedy, but obliquely, snapping shots with a concealed camera, on the sly. Arbus started out that way, too, but soon changed tactics. She needed to get closer, physically and emotionally. So she asked permission, got to know people, listened to their stories; some relationships went on for years. Arbus herself had to learn to have the courage. DIANE ARBUS: "Notes from the Margin of Spoiled Identity" (1988)ASX. By Gerry Badger, Originally Published in Phototexts, 1988 The principal issue raised by the remarkable photographs of Diane Arbus seems not to be their remarkableness, which few would dispute, but their morality.

The very potency of her images, their dangerous, disturbing allure, demands an almost instantaneous moral judgement on the part of the viewer. Arbus Reconsidered. 'Giving a camera to Diane Arbus is like giving a hand grenade to a baby,'' Norman Mailer said after seeing how she had captured him, leaning back in a velvet armchair with his legs splayed cockily.

The quip was funny, but a little off base. A camera for Arbus was like a latchkey. With one around her neck, she could open almost any door. Fearless, tenacious, vulnerable -- the combination conquered resistance. In an eye-opening sequence in ''Revelations,'' the compendious new book that is being published in tandem with a full-scale retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, you discover with a start the behind-the-scenes drama that produced her famous photograph of ''A Naked Man Being a Woman.'' Diane Arbus: humanist or voyeur? Diane Arbus killed herself, aged 48, on 26 July 1971. On the 40th anniversary of her death, it's worth reconsidering her artistic legacy. Her work remains problematic for many viewers because she transgressed the traditional boundaries of portraiture, making pictures of circus and sideshow "freaks", many of whom she formed lasting friendships with.

If Arbus undoubtedly felt at home among the outsiders she photographed, she also experienced a frisson of guilty pleasure when photographing them. "There's some thrill in going to a sideshow," she once confessed of her nocturnal visits to the circus tents of Coney Island, where performers were still earning a living in the 1960s. "I felt a mixture of shame and awe. " Her works make us question not just her motives for looking at what the critic Susan Sontag – with typical hauteur – called "people who are pathetic, pitiable, as well as repulsive", but also our own.

The "other" is not what it used to be. Arbus, Boy with a Toy Grenade, 1962. Notes on Arbus. Double Exposure. NEW YORK They remember none of it. Not the lady with the camera, arranging them by a wall at the Knights of Columbus hall in their home town of Roselle, N.J. Not the chocolate cake they had just finished, which is very faintly visible in the picture at the creases of their lips. The Wade sisters, as they were known before they each married, recall nothing about the day they gazed into the lens of Diane Arbus and became part of American photographic history.

Unless you count the dresses. "We still have them," says Colleen. "Our mother made them," says Cathleen. They were 7 years old in 1967, when Arbus found the girls at a Christmas party for local twins and triplets. It would become one of the most famous photographs of the era's most compelling photographer. They've been handed a peculiar kind of celebrity, the kind you don't ask for and certainly don't expect. Photographer_week.pdf. DIANE ARBUS - THE PHOTOGRAPHIC WORK.

Diane Arbus at Foam. DIANE ARBUS: "Flirt, Flash & Mirror" (2013) A husband and wife in the woods at a nudist camp, N.J., 1963 By Anna Solal Translated by Chris Farmer, 2013 I saw this show a few months ago in Berlin but it took some time to fully digest it. Diane Arbus. Diane Arbus. Diane Arbus. Diane Arbus (/diːˈæn ˈɑrbəs/; March 14, 1923 – July 26, 1971) was an American photographer and writer noted for black-and-white square photographs of "deviant and marginal people (dwarfs, giants, transgender people, nudists, circus performers) or of people whose normality seems ugly or surreal".[2] Arbus believed that a camera could be "a little bit cold, a little bit harsh" but its scrutiny revealed the truth; the difference between what people wanted others to see and what they really did see – the flaws.[3] A friend said that Arbus said that she was "afraid ... that she would be known simply as 'the photographer of freaks'", and that phrase has been used repeatedly to describe her.[4][5][6][7] Personal life[edit] Diane and Allan Arbus separated in 1958, and were divorced in 1969.[15] Photographic career[edit] Death[edit] Notable photographs[edit]