Le dilemme du prisonnier a enfin été testé... sur des prisonniers. Les humains sont-ils moins égoïstes, calculateurs et méfiants que ne le supposent certaines théories économiques lorsqu’ils agissent en société?

Les chercheurs Menusch Khadjavi et Andreas Lange du département d’économie de l’université de Hambourg ont testé, sans doute pour la première fois, le célèbre dilemme du prisonnier sur des prisonnières d’un pénitencier de Basse-Saxe ainsi que sur des étudiants, relate Business Insider. Leurs résultats complets seront publiés en août dans la revue Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. Et ces résultats sont surprenants. publicité Le dilemme du prisonnier, le plus célèbre de la théorie des jeux, démontre normalement que face à une incertitude concernant le choix d’un autre individu, le premier a intérêt à le trahir.

Dans le cas fictif du dilemme du prisonnier, les participants risquent jusqu'à 10 ans de prison. À lire aussi sur Slate.fr.

Catégorie:Théorie des jeux. Théorie des jeux. La théorie des jeux est un domaine des mathématiques qui s'intéresse aux interactions stratégiques des agents (appelés « joueurs »).

Les fondements mathématiques de la théorie moderne des jeux sont décrits autour des années 1920 par Ernst Zermelo dans l'article Über eine Anwendung der Mengenlehre auf die Theorie des Schachspiels, et par Émile Borel dans l'article « La théorie du jeu et les équations intégrales à noyau symétrique ». Ces idées sont ensuite développées par Oskar Morgenstern et John von Neumann en 1944 dans leur ouvrage Theory of Games and Economic Behavior qui est considéré comme le fondement de la théorie des jeux moderne. Jeux. Manueljeux. Kerckhoffs's Principle. In cryptography, Kerckhoffs's principle (also called Kerckhoffs's desiderata, Kerckhoffs's assumption, axiom, or law) was stated by Auguste Kerckhoffs in the 19th century: A cryptosystem should be secure even if everything about the system, except the key, is public knowledge.

Bringing Down the House (book) The book's main character is Kevin Lewis, an MIT graduate who was invited to join the MIT Blackjack Team in 1993.

Lewis was recruited by two of the team's top players, Jason Fisher and Andre Martinez. The team was financed by a colorful character named Micky Rosa, who had organized at least one other team to play the Vegas strip. This new team was the most profitable yet. Personality conflicts and card counting deterrent efforts at the casinos eventually ended this incarnation of the MIT Blackjack Team.

Although not revealed in the book, Kevin Lewis's real name is Jeff Ma, an MIT student who graduated with a degree in Mechanical Engineering in 1994. Mezrich acknowledges that Lewis is the sole major character based on a single, real-life individual; other characters are composites. One of the leaders of the team, Jason Fisher, is modeled in part after Mike Aponte. An Error Occurred Setting Your User Cookie.

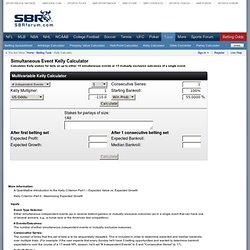

Advance Stock Pattern Scanner. Kelly criterion (long, but give it a chance!) ;-) - rec.gambling.poker. Kelly Calculator. Calculates Kelly stakes for bets on up to either 15 simultaneous events or 15 mutually exclusive outcomes of a single event.

More Information: Inputs Event Type Selector: Either simultaneous independent events (as in several distinct games) or mutually exclusive outcomes (as in a single event that can have one of several winners, e.g., a horse race or the American Idol competition). # Events/Outcomes: The number of either simultaneous independent events or mutually exclusive outcomes.

Consecutive Series: The number of times that this set of bets is to be sequentially repeated. Kelly. Proebsting's paradox. In probability theory, Proebsting's paradox is an argument that appears to show that the Kelly criterion can lead to ruin.

Although it can be resolved mathematically, it raises some interesting issues about the practical application of Kelly, especially in investing. It was named and first discussed by Edward O. Thorp in 2008.[1] Statement of the paradox[edit] If a bet is equally likely to win or lose, and pays b times the stake for a win, the Kelly bet is: times wealth.[2] For example, if a 50/50 bet pays 2 to 1, Kelly says to bet 25% of wealth. Now suppose a gambler is offered 2 to 1 payout and bets 25%. Because if he wins he will have 1.5 (the 0.5 from winning the 25% bet at 2 to 1 odds) plus 5f*; and if he loses he must pay 0.25 from the first bet, and f* from the second.

Which can be rewritten: So f* = 0.225. The paradox is that the total bet, 0.25 + 0.225 = 0.475, is larger than the 0.4 Kelly bet if the 5 to 1 odds are offered from the beginning. Gambling and information theory. Statistical inference might be thought of as gambling theory applied to the world around.

The myriad applications for logarithmic information measures tell us precisely how to take the best guess in the face of partial information.[1] In that sense, information theory might be considered a formal expression of the theory of gambling. It is no surprise, therefore, that information theory has applications to games of chance.[2] Kelly Betting[edit] Kelly betting or proportional betting is an application of information theory to investing and gambling. Its discoverer was John Larry Kelly, Jr. Part of Kelly's insight was to have the gambler maximize the expectation of the logarithm of his capital, rather than the expected profit from each bet. Kelly criterion. In probability theory and intertemporal portfolio choice, the Kelly criterion, Kelly strategy, Kelly formula, or Kelly bet, is a formula used to determine the optimal size of a series of bets.

In most gambling scenarios, and some investing scenarios under some simplifying assumptions, the Kelly strategy will do better than any essentially different strategy in the long run (that is, over a span of time in which the observed fraction of bets that are successful equals the probability that any given bet will be successful). It was described by J. L. Kelly, Jr in 1956.[1] The practical use of the formula has been demonstrated.[2][3][4] In recent years, Kelly has become a part of mainstream investment theory[7] and the claim has been made that well-known successful investors including Warren Buffett[8] and Bill Gross[9] use Kelly methods.

Statement[edit] where: If the gambler has zero edge, i.e. if b = q / p, then the criterion recommends the gambler bets nothing. 1. 2.