Lilith. Lilith (Hebrew: לילית; lilit, or lilith) is a Hebrew name for a figure in Jewish mythology, developed earliest in the Babylonian Talmud, who is generally thought to be in part derived from a class of female demons Līlīṯu in Mesopotamian texts of Assyria and Babylonia.

Evidence in later Jewish materials is plentiful, but little information has been found relating to the original Akkadian and Babylonian view of these demons. The relevance of two sources previously used to connect the Jewish Lilith to an Akkadian Lilitu—the Gilgamesh appendix and the Arslan Tash amulets—are now both disputed by recent scholarship.[1] The two problematic sources are discussed below.[2] The Hebrew term Lilith or "Lilit" (translated as "Night creatures", "night monster", "night hag", or "screech owl") first occurs in Isaiah 34:14, either singular or plural according to variations in the earliest manuscripts, though in a list of animals. Etymology[edit] In Akkadian the terms lili and līlītu mean spirits. [edit] Lilith. Lilith (sumerisch DINGIRLIL.du/LIL.LU, babylonisch Lilītu, hebr.

לילית, ‚weiblicher Dämon‘[1]) war eine Göttin der sumerischen Mythologie. Zunächst wohnte sie im Stamm des Weltenbaumes, nachdem dieser jedoch auf Befehl Inannas hin gespalten wurde, floh Lilith in ein unbekanntes Gebiet. In der Folge wurde sie sowohl im alten Orient als auch in späteren Quellen häufig als weibliches geflügeltes Mischwesen dargestellt. Neben mythologischen und magischen Schriften finden sich auch literarische Texte, in denen Lilith erwähnt wird. Alleine kommt sie nur selten vor, häufig ist in den mesopotamischen Quellen die gemeinsame Nennung von lilû, einem männlichen Dämon, lilītu (Lilith) und (w)ardat lilî (‚Tochter des Lilû‘).

Etymologie[Bearbeiten] Neben der sumerischen Form DLIL.LU bestanden weitere literarische Bezeichnungen sowie Gleichsetzungen mit anderen Gottheiten. Die mythologischen Zusammenhänge und Wandlungen lassen eine eindeutige Übersetzung deshalb nicht zu. Altsumerische Zeit[Bearbeiten] Eve and the Identity of Women: 7. Eve & Lilith.

In an effort to explain inconsistencies in the Old Testament, there developed in Jewish literature a complex interpretive system called the midrash which attempts to reconcile biblical contradictions and bring new meaning to the scriptural text.

Employing both a philological method and often an ingenious imagination, midrashic writings, which reached their height in the 2nd century CE, influenced later Christian interpretations of the Bible. Inconsistencies in the story of Genesis, especially the two separate accounts of creation, received particular attention. Later, beginning in the 13th century CE, such questions were also taken up in Jewish mystical literature known as the Kabbalah. According to midrashic literature, Adam's first wife was not Eve but a woman named Lilith, who was created in the first Genesis account. Only when Lilith rebelled and abandoned Adam did God create Eve, in the second account, as a replacement. Lilith also personified licentiousness and lust. Lilith - semen demon or feminist icon? Exactly who or what is Lilith?

Now regarded by Jewish esoteric tradition to be one of the four queens of demons, the nature of Lilith has undergone many reinterpretations throughout Jewish history. [Illustration: etching of Lilith on a metal amulet] The origins of Lilith are probably found in the Mesopotamian lilu, or “aerial spirit.” Some features of Lilith in later Jewish tradition also resemble those of Lamashtu, a Babylonian demoness who causes infant death. There is one mention of lilot (plural) in the Bible (Isa. 34:14), but references to lilith demons only become common in post-Biblical Jewish sources. Furthermore, the characterization of Lilith as a named demonic personality really only begins late in antiquity.

Jewish tradition gradually fixes on lilith as a female demon. Looking for Lilith. The feminist critique of conventional values has not overlooked the Jewish tradition.

Whether or not one acknowledges the validity of all the charges that have been leveled against the treatment of women in Jewish law and theology, it is hardly possible to ignore these issues. As one who is normally sympathetic with feminist aspirations, I have often been disappointed with the scholarly standards of the debate, especially when it has been directed towards the classical texts of Judaism. In the course of polemical ideological exchanges, I find too frequently that sweeping generalizations are being supported by flimsy or questionable evidence, with a disturbing disregard for factual accuracy and historical context.

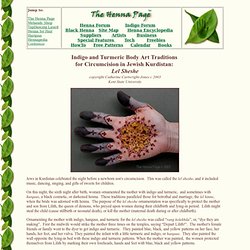

As an example of this sort of scholarly sloppiness, I wish to discuss an intriguing Hebrew legend that has found its way into dozens of recent works about Jewish attitudes towards women. Return to the main index of Eliezer Segal's articles. The Encyclopedia of Henna - Circumcision Body Art Traditions in Jewish Kurdistan. Indigo and Turmeric Body Art Traditions for Circumcision in Jewish Kurdistan: Lel Sheshe copyright Catherine Cartwright-Jones c 2003 Kent State University Jews in Kurdistan celebrated the night before a newborn son's circumcision.

This was called the lel sheshe, and it included music, dancing, singing, and gifts of sweets for children. On this night, the sixth night after birth, women ornamented the mother with indigo and turmeric, and sometimes with harquus, a black cosmetic, or darkened henna. These traditions paralleled those for betrothal and marriage, the lel hinne, when the bride was adorned with henna.