Scientists discover new variability in iron supply to the oceans with climate implications. The supply of dissolved iron to oceans around continental shelves has been found to be more variable by region than previously believed -- with implications for future climate prediction.

Iron is key to the removal of carbon dioxide from Earth's atmosphere as it promotes the growth of microscopic marine plants (phytoplankton), which mop up the greenhouse gas and lock it away in the ocean. A new study, led by researchers based at the National Oceanography Centre Southampton, has found that the amount of dissolved iron released into the ocean from continental margins displays variability not currently captured by ocean-climate prediction models.

This could alter predictions of future climate change because iron, a key micronutrient, plays an important role in the global carbon cycle. Continental margins are a major source of dissolved iron to the oceans and therefore an important factor for climate prediction models. Unprecedented trade wind strength is shifting global warming to the oceans, but for how much longer? Research looking at the effects of Pacific Ocean cycles has been gradually piecing together the puzzle explaining why the rise of global surface temperatures has slowed over the past 10 to 15 years.

A new study just published in Nature Climate Change, led by Matthew England at the University of New South Wales, adds yet another piece to the puzzle by examining the influence of Pacific trade winds. While the rate of surface temperature warming has slowed in recent years, several studies have shown that the warming of the planet as a whole has not. This suggests that the slowed surface warming is not due as much to external factors like decreased solar activity or more pollutants in the atmosphere blocking sunlight, but more due to internal factors shifting the heat into the oceans. Unprecedented trade wind strength is shifting global warming to the oceans, but for how much longer? La Niña. La Niña (/lɑːˈniːnjə/, Spanish pronunciation: [la ˈniɲa]) is a coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon that is the counterpart of El Niño as part of the broader El Niño–Southern Oscillation climate pattern.

During a period of La Niña, the sea surface temperature across the equatorial Eastern Central Pacific Ocean will be lower than normal by 3–5 °C. In the United States, an appearance of La Niña happens for at least five months of La Niña conditions. The name La Niña originates from Spanish, meaning "little girl," analogous to El Niño meaning "little boy. " La Niña, sometimes informally called "anti-El Niño", is the opposite of El Niño, where the latter corresponds instead to a higher sea surface temperature by a deviation of at least 0.5 °C, and its effects are often the reverse of those of El Niño. El Niño is known for its potentially catastrophic impact on the weather along the Chilean, Peruvian, New Zealand, and Australian coasts, among others. Effects[edit] El Niño. "El Nina" redirects here.

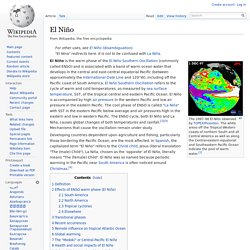

It is not to be confused with La Niña. The 1997–98 El Niño observed by TOPEX/Poseidon. The white areas off the Tropical Western coasts of northern South and all Central America as well as along the Central-eastern equatorial and Southeastern Pacific Ocean indicate the pool of warm water.[1] El Niño is the warm phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (commonly called ENSO) and is associated with a band of warm ocean water that develops in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific (between approximately the International Date Line and 120°W), including off the Pacific coast of South America.

El Niño Southern Oscillation refers to the cycle of warm and cold temperatures, as measured by sea surface temperature, SST, of the tropical central and eastern Pacific Ocean. Developing countries dependent upon agriculture and fishing, particularly those bordering the Pacific Ocean, are the most affected. Definition[edit] Wavier jet stream 'may drive weather shift' 15 February 2014Last updated at 14:32 ET By Pallab Ghosh Science correspondent, BBC News, Chicago Pallab Ghosh: "We may have to get used to winters where spells of weather go on for weeks - or even months" The main system that helps determine the weather over Northern Europe and North America may be changing, research suggests.

The study shows that the so-called jet stream has increasingly taken a longer, meandering path. This has resulted in weather remaining the same for more prolonged periods. Www.ldeo.columbia.edu/~broecker/Home_files/TheRoleOceClim.pdf.