Decision Making. Choice modelling. Truism. A truism is a claim that is so obvious or self-evident as to be hardly worth mentioning, except as a reminder or as a rhetorical or literary device and is the opposite of falsism.[1] The word may also be used with a different sense in rhetoric, to disguise the fact that a proposition is really just an opinion.

Similarly, stating an accepted truth about life in general can also be called a truism. Satisficing. Satisficing is a decision-making strategy or cognitive heuristic that entails searching through the available alternatives until an acceptability threshold is met.[1] This is contrasted with optimal decision making, an approach that specifically attempts to find the best alternative available.

The term satisficing, a portmanteau of satisfy and suffice,[2] was introduced by Herbert A. Simon in 1956,[3] although the concept "was first posited in Administrative Behavior, published in 1947. "[4][5] Simon used satisficing to explain the behavior of decision makers under circumstances in which an optimal solution cannot be determined. He pointed out that human beings lack the cognitive resources to optimize: We can rarely evaluate all outcomes with sufficient precision, usually do not know the relevant probabilities of outcomes, and possess only limited memory.

Errors and Bias in Judgment. The fact that people's intuitive decisions are often strongly and systematically biased has been firmly established over the past 50 years by literally hundreds of empirical studies.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman received the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics for his work in this area. The conclusion reached by Kahneman and his colleagues is that people use unconscious shortcuts, termed heuristics, to help them make decisions. "In general, these heuristics are useful, but sometimes they lead to severe and systematic errors" [1]. Understanding heuristics and the errors they cause is important because it can help us find ways to counteract them. For example, when judging distance people use a heuristic that equates clarity with proximity. Figure 1: Haze tricks us into thinking objects are further away. Sunk costs.

In economics and business decision-making, a sunk cost is a retrospective (past) cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered.

Sunk costs are sometimes contrasted with prospective costs, which are future costs that may be incurred or changed if an action is taken. Both retrospective and prospective costs may be either fixed (continuous for as long as the business is in operation and unaffected by output volume) or variable (dependent on volume) costs. [1] Sherman notes, however, that many economists consider it a mistake to classify sunk costs as "fixed" or "variable. " For example, if a firm sinks $1 million on an enterprise software installation, that cost is "sunk" because it was a one-time expense and cannot be recovered once spent. A "fixed" cost would be monthly payments made as part of a service contract or licensing deal with the company that set up the software.

Sunk costs should not affect the rational decision-maker's best choice. Prospect theory. The paper "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk"[1] has been called a "seminal paper in behavioral economics".[2] Model[edit] The formula that Kahneman and Tversky assume for the evaluation phase is (in its simplest form) given by where is the overall or expected utility of the outcomes to the individual making the decision, are the potential outcomes and their respective probabilities.

A priori and a posteriori. The terms a priori ("from the earlier") and a posteriori ("from the later") are used in philosophy (epistemology) to distinguish two types of knowledge, justification, or argument: A priori knowledge or justification is independent of experience (for example "All bachelors are unmarried").

Galen Strawson has stated that an a priori argument is one in which "you can see that it is true just lying on your couch. You don't have to get up off your couch and go outside and examine the way things are in the physical world. You don't have to do any science. There are many points of view on these two types of knowledge, and their relationship is one of the oldest problems in modern philosophy. Utility. Economic definitions[edit] In economics, utility is a representation of preferences over some set of goods and services.

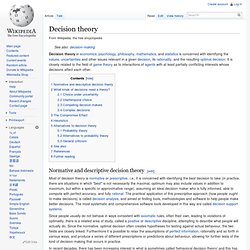

Preferences have a (continuous) utility representation so long as they are transitive, complete, and continuous. Decision theory. Normative and descriptive decision theory[edit] Since people usually do not behave in ways consistent with axiomatic rules, often their own, leading to violations of optimality, there is a related area of study, called a positive or descriptive discipline, attempting to describe what people will actually do.

Since the normative, optimal decision often creates hypotheses for testing against actual behaviour, the two fields are closely linked. Furthermore it is possible to relax the assumptions of perfect information, rationality and so forth in various ways, and produce a series of different prescriptions or predictions about behaviour, allowing for further tests of the kind of decision-making that occurs in practice. Risk. Risk is the potential of losing something of value, weighed against the potential to gain something of value.

Values (such as physical health, social status, emotional well being or financial wealth) can be gained or lost when taking risk resulting from a given action, activity and/or inaction, foreseen or unforeseen. Risk can also be defined as the intentional interaction with uncertainty. Risk perception is the subjective judgment people make about the severity of a risk, and may vary person to person. Any human endeavor carries some risk, but some are much riskier than others.[1] Definitions[edit] Firefighters at work. Decision making. Sample flowchart representing the decision process to add a new article to Wikipedia.

Decision analysis. History and methodology[edit] The term decision analysis was coined in 1964 by Ronald A. Howard,[1] who since then, as a professor at Stanford University, has been instrumental in developing much of the practice and professional application of DA. Graphical representation of decision analysis problems commonly use influence diagrams and decision trees. Both of these tools represent the alternatives available to the decision maker, the uncertainty they face, and evaluation measures representing how well they achieve their objectives in the final outcome. Uncertainties are represented through probabilities and probability distributions. Decision analysis is used by major corporations to make multi-billion dollar capital investments.