Perception Since the rise of experimental psychology in the 19th Century, psychology's understanding of perception has progressed by combining a variety of techniques.[3] Psychophysics quantitatively describes the relationships between the physical qualities of the sensory input and perception.[5] Sensory neuroscience studies the brain mechanisms underlying perception. Perceptual systems can also be studied computationally, in terms of the information they process. Perceptual issues in philosophy include the extent to which sensory qualities such as sound, smell or color exist in objective reality rather than in the mind of the perceiver.[3] The perceptual systems of the brain enable individuals to see the world around them as stable, even though the sensory information is typically incomplete and rapidly varying. Human and animal brains are structured in a modular way, with different areas processing different kinds of sensory information. Process and terminology[edit] Perception and reality[edit]

Meaning (philosophy) Philosophical conception of meaning In philosophy—more specifically, in its sub-fields semantics, semiotics, philosophy of language, metaphysics, and metasemantics—meaning "is a relationship between two sorts of things: signs and the kinds of things they intend, express, or signify".[1] The types of meanings vary according to the types of the thing that is being represented. There are: the things, which might have meaning;things that are also signs of other things, and therefore are always meaningful (i.e., natural signs of the physical world and ideas within the mind);things that are necessarily meaningful, such as words and nonverbal symbols. The major contemporary positions of meaning come under the following partial definitions of meaning: Substantive theories of meaning [edit] Correspondence theory For coherence theories in general, the assessment of meaning and truth requires a proper fit of elements within a whole system. Constructivist theory Other truth theories of meaning W.

Memory Definition & Types of Memory For us to recall events, facts or processes, we have to commit them to memory. The process of forming a memory involves encoding, storing, retaining and subsequently recalling information and past experiences. Cognitive psychologist Margaret W. Matlin has described memory as the “process of retaining information over time.” When they are asked to define memory, most people think of studying for a test or recalling where we put the car keys. The process of encoding a memory begins when we are born and occurs continuously. Important memories typically move from short-term memory to long-term memory. Motivation is also a consideration, in that information relating to something that you have a keen interest in is more likely to be stored in your long-term memory. We are typically not aware of what is in our memory until we need to use that bit of information. Implicit memory is sometimes referred to as unconscious memory or automatic memory. Some examples of procedural memory: Related:

Thought Cognitive process independent of the senses In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to conscious cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, and deliberation. But other mental processes, like considering an idea, memory, or imagination, are also often included. These processes can happen internally independent of the sensory organs, unlike perception. But when understood in the widest sense, any mental event may be understood as a form of thinking, including perception and unconscious mental processes. Various types of thinking are discussed in the academic literature. Definition[edit] The word thought comes from Old English þoht, or geþoht, from the stem of þencan "to conceive of in the mind, consider".[21] Theories of thinking[edit] Various theories of thinking have been proposed.[22] They aim to capture the characteristic features of thinking.

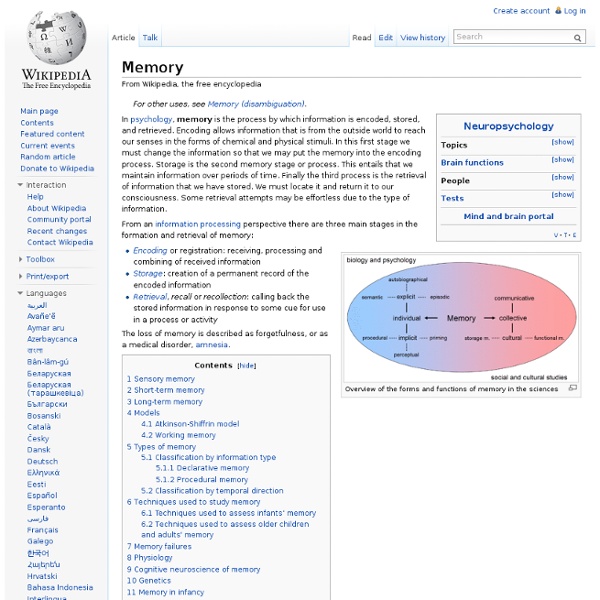

Memory and retention in learning Model of the Memory Process Human memory is the process in which information and material is encoded, stored and retrieved in the brain.[1] Memory is a property of the central nervous system, with three different classifications: short-term, long-term and sensory memory.[2] The three types of memory have specific, different functions but each are equally important for memory processes. Sensory information is transformed and encoded in a certain way in the brain, which forms a memory representation.[3] This unique coding of information creates a memory.[3] Memory and retention are linked because any retained information is kept in human memory stores, therefore without human memory processes, retention of material would not be possible.[4] In addition, memory and the process of learning are also closely connected. Types of memory[edit] Long-term[edit] Types of Long-term Memory Short-term[edit] Short-term memory is responsible for retaining and processing information very temporarily.

What Is Memory? - The Human Memory Memory is our ability to encode, store, retain and subsequently recall information and past experiences in the human brain. It can be thought of in general terms as the use of past experience to affect or influence current behaviour. Memory is the sum total of what we remember, and gives us the capability to learn and adapt from previous experiences as well as to build relationships. It is the ability to remember past experiences, and the power or process of recalling to mind previously learned facts, experiences, impressions, skills and habits. It is the store of things learned and retained from our activity or experience, as evidenced by modification of structure or behaviour, or by recall and recognition. Etymologically, the modern English word “memory” comes to us from the Middle English memorie, which in turn comes from the Anglo-French memoire or memorie, and ultimately from the Latin memoria and memor, meaning "mindful" or "remembering".

Mental process A specific instance of engaging in a cognitive process is a mental event. The event of perceiving something is, of course, different from the entire process, or capacity of perception—one's ability to perceive things. In other words, an instance of perceiving is different from the ability that makes those instances possible. See also[edit] External links[edit] Mental Processes at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) Models of consciousness Aspect of consciousness research Models of consciousness are used to illustrate and aid in understanding and explaining distinctive aspects of consciousness. Sometimes the models are labeled theories of consciousness. Anil Seth defines such models as those that relate brain phenomena such as fast irregular electrical activity and widespread brain activation to properties of consciousness such as qualia. Seth allows for different types of models including mathematical, logical, verbal and conceptual models.[1][2] Neural correlates of consciousness [edit] The Neural correlates of consciousness (NCC) formalism is used as a major step towards explaining consciousness. Dehaene–Changeux model The Dehaene–Changeux model (DCM), also known as the global neuronal workspace or the global cognitive workspace model is a computer model of the neural correlates of consciousness programmed as a neural network. Electromagnetic theories of consciousness Orchestrated objective reduction Multiple drafts model

Human Benchmark Imagination Creative ability Imagination is the production of sensations, feelings and thoughts informing oneself.[1] These experiences can be re-creations of past experiences, such as vivid memories with imagined changes, or completely invented and possibly fantastic scenes.[2] Imagination helps apply knowledge to solve problems and is fundamental to integrating experience and the learning process.[3][4][5] Imagination is the process of developing theories and ideas based on the functioning of the mind through a creative division. Drawing from actual perceptions, imagination employs intricate conditional processes that engage both semantic and episodic memory to generate new or refined ideas.[6] This part of the mind helps develop better and easier ways to accomplish tasks, whether old or new. The English word "imagination" originates from the Latin term "imaginatio," which is the standard Latin translation of the Greek term "phantasia." The Latin term also translates to "mental image" or "fancy."