Air pollution in Victorian-era Britain – its effects on health now revealed The health hazards of atmospheric pollution have become a major concern in Britain and around the world. Much less is known about its effects in the past. But economic historians have come up with new ways of shedding light on this murky subject. In the early industrial age, Britain was famous for its dark satanic mills. And the industrial revolution, which did so much to raise income and wealth, depended almost entirely on one fuel source: coal. Coal supplied domestic hearths and coal-powered steam engines turned the wheels of industry and transport. In Britain, emissions of black smoke were up to 50 times higher in the decades before the clean air acts than they are today. Unregulated coal burning darkened the skies in Britain’s industrial cities, and it was plain for all to see. In the absence of data on emissions, economic historians have come up with a novel way of measuring its effects. Coal intensity linked to early death Geography mattered.

Coronavirus, la stratégie d’immunité de groupe ne fonctionnera pas, par Alexis Toulet La « mesure forte » annoncée par Emmanuel Macron lors de son allocution de jeudi soir 12 mars était la fermeture de toutes les écoles. Sera-t-elle suffisante pour freiner la progression de l’épidémie ? Rappelons que l’Italie a fermé toutes ses écoles et universités le 4 mars, alors qu’elle comptait 107 morts du coronavirus – ce qui n’a pas empêché que le 13 mars elle en recense douze fois plus. Mesure à coup sûr utile, il y a toutes raisons de croire que la fermeture des écoles sera cependant insuffisante à elle seule pour freiner véritablement la propagation du virus. Ce qui laisse ouverte la question de la véritable stratégie choisie par le gouvernement français pour lutter contre le coronavirus. On peut encore remarquer que Emmanuel Macron a également demandé aux personnes les plus âgées et les plus malades de rester autant que possible chez elles C’est en tout cas la stratégie explicitement revendiquée par le gouvernement britannique de Boris Johson. Nulles. Les conséquences de l’échec

Aerosol transmission of Covid-19: A room, a bar and a classroom: how the coro... The coronavirus is spread through the air, especially in indoor spaces. While it is not as infectious as measles, scientists now openly acknowledge the role played by the transmission of aerosols – tiny contagious particles exhaled by an infected person that remain suspended in the air of an indoor environment. How does the transmission work? These are respiratory droplets that are less than 100 micrometers in diameter that can remain suspended in the air for hours 1,200 aerosols are released for each droplet These are particles that are larger than 300 micrometers and, due to air currents, fall to the ground in seconds Without ventilation, aerosols remain suspended in the air, becoming increasingly concentrated as time goes by. Breathing, speaking and shouting At the beginning of the pandemic, it was believed that the large droplets we expel when we cough or sneeze were the main vehicle of transmission. Each orange dot represents a dose of respiratory of infecting someone if inhaled School

20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history | Live Science Throughout the course of history, disease outbreaks have ravaged humanity, sometimes changing the course of history and, at times, signaling the end of entire civilizations. Here are 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics, dating from prehistoric to modern times. Related: Spanish flu: The deadliest pandemic in history 1. About 5,000 years ago, an epidemic wiped out a prehistoric village in China. Before the discovery of Hamin Mangha, another prehistoric mass burial that dates to roughly the same time period was found at a site called Miaozigou, in northeastern China. 2. Around 430 B.C., not long after a war between Athens and Sparta began, an epidemic ravaged the people of Athens and lasted for five years. What exactly this epidemic was has long been a source of debate among scientists; a number of diseases have been put forward as possibilities, including typhoid fever and Ebola. 3. Related: Read a free issue of All About History magazine 4. Named after St. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12.

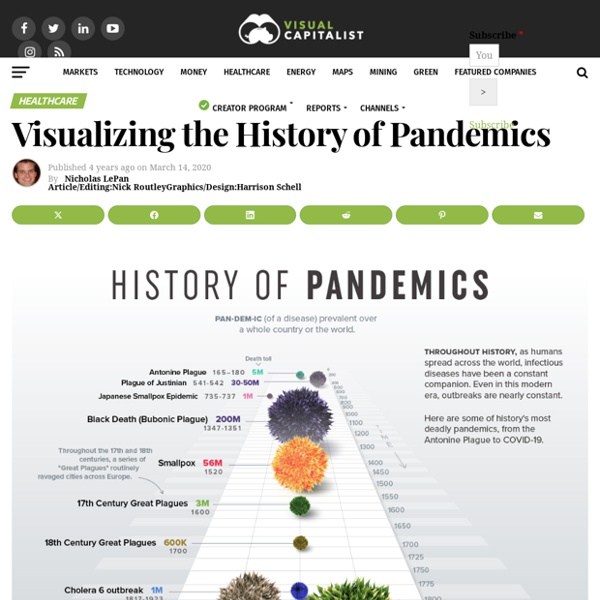

The History of Pandemics by Death Tol Chernobyl Disaster in rare pictures, 1986 - Rare Historical Photos Coronavirus : comment l’Europe est devenue l’« épicentre » de la pandémie « L’Europe est actuellement à l’épicentre de la pandémie du Covid-19 », a déclaré, vendredi 13 mars, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, le directeur de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS). De fait, l’épidémie commençant sa décrue en Chine, son foyer d’origine, elle s’est étendue dans le reste du monde et particulièrement au sein du continent européen. Celui-ci concentre désormais 37,8 % des cas cumulés enregistrés au niveau mondial depuis le début de l’épidémie, il y a trois mois, et devrait rapidement passer devant la Chine, qui enregistre jusqu’ici 41 % des cas. Les chiffres : Suivez la propagation de la pandémie sur cette page Inertie Des propos fermes nourris notamment par l’inertie des gouvernements européens devant la rapidité de propagation de la maladie. En France, les premières mesures visant à interdire les rassemblements de plus de 5 000 personnes sont appliquées dès le 5 mars, alors que le pays compte environ 380 cas confirmés. La plupart des malades sont européens Gary Dagorn

« La question de l'origine du SARS-CoV-2 se pose sérieusement » Près d'un an après que l'on a identifié le coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, les chercheurs n'ont toujours pas déterminé comment il a pu se transmettre à l'espèce humaine. Le virologue Étienne Decroly fait le point sur les différentes hypothèses, dont celle de l’échappement accidentel d’un laboratoire. Tandis qu’on assiste à une course de vitesse pour la mise au point de vaccins ou de traitements, pourquoi est-il si important de connaître la généalogie du virus qui provoque la pandémie de Covid-19 ?Étienne Decroly1 : SARS-CoV-2, qui a rapidement été identifié comme le virus à l’origine de la Covid-19 est, après le SARS-CoV en 2002 et le MERS-CoV en 2012, le troisième coronavirus humain responsable d’un syndrome respiratoire sévère à avoir émergé au cours des vingt dernières années. Dès les premières semaines de la pandémie, alors qu’on ne savait encore pas grand-chose du virus, sa probable origine animale a très vite été pointée. Groupe de chauves-souris dans une grotte de Birmanie. A. ©L.

Coronavirus Update (Live): 7,582,164 Cases and 423,067 Deaths from COVID-19 Virus Pandemic - Worldometer COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic L’ultima peste italiana La storia del mondo ha conosciuto frequenti e terribili emergenze di salute pubblica, a cominciare dalle epidemie di peste, alcune delle quali immortalate dalla letteratura: si ricordino, fra le tante, quella del 1348 di cui all’opera di Giovanni Boccaccio, o quella del 1630 che vive indelebilmente nelle celebri pagine manzoniane. In tempi più lontani, l’argomento era stato trattato anche da Tucidide nella descrizione della peste ateniese del 430 avanti Cristo in cui era scomparso Pericle, e prima ancora, nel libro biblico di Samuele. La peste ha modificato sensibilmente gli assetti etnici e demografici anche in Italia: ad esempio, è ciò che accadde nell’Alto Adriatico quando la Repubblica di Venezia dovette sopperire con forti immigrazioni slave in Istria e Dalmazia ai vuoti abissali scavati dalle epidemie nel tessuto sociale del territorio. Si tratta di un fenomeno le cui conseguenze indirette si sono fatte sentire sino ai nostri giorni.

Even at the height of the gold rush, Melbourne was an absolute dump There was a time in the 19th century when Melbourne was considered one of the richest cities in the world, but there were two things it hadn't worked out. Number 1, how to get rid of its rubbish; and 2, what to do with its, well, number twos. The gold rush brought with it the promise of streets paved with gold, but in Melbourne there were streets literally made of garbage. Melbourne was a dump. Parks, rivers, streets, footpaths and vacant lots were strewn with Melburnians' refuse. In 1888 a Royal Commission was ordered into sanitary conditions in Melbourne which found people were dumping their garbage wherever they could find empty space. "Streets are being made of this refuse," the commission reported, referring to the practise of digging up vacant land used as illegal dumps and using that material to build roads in the city. It was also used to bury existing properties entirely as part of a council plan in the 1850s to bring low-lying blocks up to a uniform street level.