Open Source Shakespeare: search Shakespeare's works, read the texts

Greek Gods List • Names of the Greek Gods

A Complete List of Greek Gods, Their Names & Their Realms of Influence There have been many Greek gods mentioned across thousands of stories in Greek mythology – from the Olympian gods all the way down to the many minor gods. The gods, much like the Greek goddesses of history, have very exaggerated personalities and they are plagued with personal flaws and negative emotions despite they immortality and superhero-like powers. This page is a list of the names of Greek gods in ancient mythology and their roles. Achelous The patron god of the “silver-swirling” Achelous River. Aeolus Greek god of the winds and air Aether Primordial god of the upper air, light, the atmosphere, space and heaven. Alastor God of family feuds and avenger of evil deeds. Apollo Olympian god of music, poetry, art, oracles, archery, plague, medicine, sun, light and knowledge. Ares God of war. Aristaeus Minor patron god of animal husbandry, bee-keeping, and fruit trees. Asclepius Atlas The Primordial Titan of Astronomy. Attis Boreas

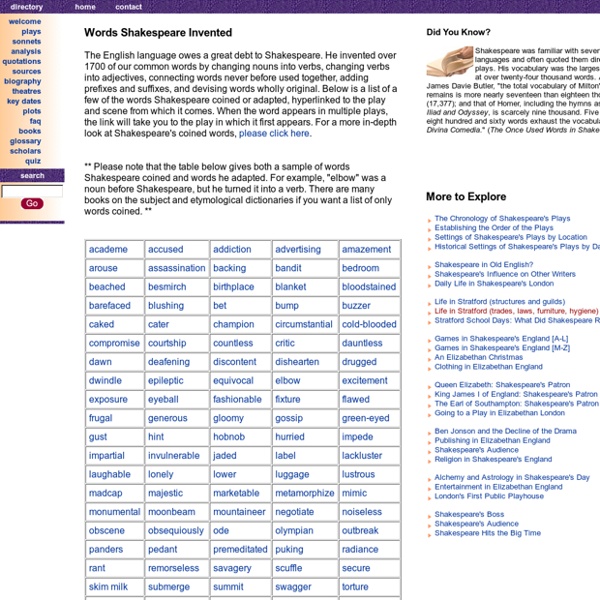

Words and Phrases Coined by Shakespeare

Words and Phrases Coined by Shakespeare NOTE: This list (including some of the errors I originally made) is found in several other places online. That's fine, but I've asked that folks who want this on their own sites mention that I am the original compiler. For many English-speakers, the following phrases are familiar enough to be considered common expressions, proverbs, and/or clichés. I compiled these from multiple sources online in 2003. How many of these are true coinages by "the Bard", and how many are simply the earliest written attestations of a word or words already in use, I can't tell you. A few words are first attested in Shakespeare and seem to have caused extra problems for the typesetters. The popular book Coined by Shakespeare acknowledges that it is presenting first attestations rather than certain inventions. Words like "anchovy", "bandit", and "zany" are just first attestations of loan-words. Right now I'm in the process of referencing these. scalpel_blade@yahoo.com

The Sonnets

You can buy the Arden text of these sonnets from the Amazon.com online bookstore: Shakespeare's Sonnets (Arden Shakespeare: Third Series) I. FROM fairest creatures we desire increase,II.

Dictionary A Terms - Star Trek Online Academy

A2B - Auxiliary to Battery aa - Anti-aliasing. A technique for minimizing distortions. Ab - Ambush (Tactical Ability) ability - In Star Trek Online abilities are either passive or active. ablative armor - A type of protective hull plating used on starships, which possesses a capability for rapidly dissipating the energy impacts from directed energy weapon fire. able crewmen - In Star Trek Online, able crewmen are members of the ship's crew which can work to repair the subsystems of the ship. academy - A place for special training. acc - Accuracy accept - Consent to receive accolade - An award granted as an acknowledgement of accomplishing something. account bank - In Star Trek Online this is a bank that can be accessed by all characters in an account. accuracy - How precise something is. acronym - A word formed by the initials of other words. admiral - The rank in a military organization, usually between Vice Admiral and Fleet Admiral. AE - Advanced Escort AF - Aceton Field (Engineering Ability)

translations of jabberwocky

Jabberwocky VariationsHome : Translations NEWEST (November 1998) Endraperós Josep M. Afrikaans Die Flabberjak Linette Retief. Choctaw Chabbawaaki Aaron Broadwell. Czech Zxvahlav Jaroslav Císarx. Danish Jabberwocky Mogens Jermiin Nissen. Dutch De Krakelwok Ab Westervaarder & René Kurpershoek. Esperanto Gxaberuxoko Mark Armantrout. Estonian Jorruline Risto Järv. French Le Jaseroque Frank L. Bredoulocheux. Le Berdouilleux André Bay. German Der Jammerwoch Robert Scott. Greek I Iabberioki Mary Matthews. Hebrew éðåòèô Aaron Amir. Pitoni. Hungarian Szajkóhukky Weó´res Sándor. Italian Il Ciarlestrone Adriana Crespi. Klingon ja'pu'vawqoy keith lim. Latin Gaberbocchus Hassard H. Norwegian Dromeparden Zinken Hopp. Polish Dz~abbersmok Maciej S/lomczyñski. Portuguese Jaguardarte Augusto de Campos. Rumanian Traxncaxniciada Frida Papadache. Russian âáòíáçìïô E. Barmaglot. Umzari U. Slovak Taradúr Juraj & Viera Vojtek. Spanish Chacaloco Erwin Brea. Swedish Jabberwocky [translator unknown]. Welsh Siaberwoci Selyf Roberts. Yiddish

Thesaurus

How do I use OneLook's thesaurus / reverse dictionary? OneLook helps you find words for any type of writing. Similar to a traditional thesaurus, it find synonyms and antonyms, but it offers much greater depth and flexibility. Simply enter a single word, a few words, or even a whole sentence to describe what you need. What are some examples? Exploring the results Click on any result to see definitions and usage examples tailored to your search, as well as links to follow-up searches and additional usage information when available. Ordering the results Your results will initially appear with the most closely related word shown first, the second-most closely shown second, and so on. Filtering the results You can refine your search by clicking on the "Advanced filters" button on the results page. I'm only looking for synonyms! For some kinds of searches only the first result or the first few results are truly synonyms or good substitutions for your search word. What are letter patterns? Privacy

Binge-watch is Collins' dictionary's Word of the Year

Collins English Dictionary has chosen binge-watch as its 2015 Word of the Year. Meaning "to watch a large number of television programmes (especially all the shows from one series) in succession", it reflects a marked change in viewing habits, due to subscription services like Netflix. Lexicographers noticed that its usage was up 200% on 2014. Other entries include dadbod, ghosting and clean eating. Helen Newstead, Head of Language Content at Collins, said: "The rise in usage of 'binge-watch' is clearly linked to the biggest sea change in our viewing habits since the advent of the video recorder nearly 40 years ago. "It's not uncommon for viewers to binge-watch a whole season of programmes such as House of Cards or Breaking Bad in just a couple of evenings - something that, in the past, would have taken months - then discuss their binge-watching on social media." Those partaking in binge-watching run the risk of dadbod, one of ten in the word of the year list.

User-submitted name Asana - Behind the Name

Submitted names are contributed by users of this website. The accuracy of these name definitions cannot be guaranteed. Submitted Name (1) Save Gender Feminine Edit Status Status Contributor Contrib.Asana on 4/16/2008 Meaning & History The name Asana is a derivative of Hassan. Submitted Name (2) Scripts 旭菜, 旭凪, 旭和, 朝菜, 朝凪, 朝南, 朝和, 麻菜 etc. Pronounced Pron. ah-sah-nah