James A. Garfield James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) served as the 20th President of the United States (1881), after completing nine consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1863–81). Garfield's accomplishments as President included a controversial resurgence of Presidential authority above Senatorial courtesy in executive appointments; energizing U.S. naval power; and purging corruption in the Post Office Department. Garfield made notable diplomatic and judiciary appointments, including a U.S. Supreme Court justice. Garfield appointed several African-Americans to prominent federal positions. Garfield's presidency lasted just 200 days—from March 4, 1881, until his death on September 19, 1881, as a result of being shot by assassin Charles J. Garfield was raised in humble circumstances on an Ohio farm by his widowed mother and elder brother, next door to their cousins, the Boyntons, with whom he remained very close. Childhood[edit] Birthplace of James Garfield

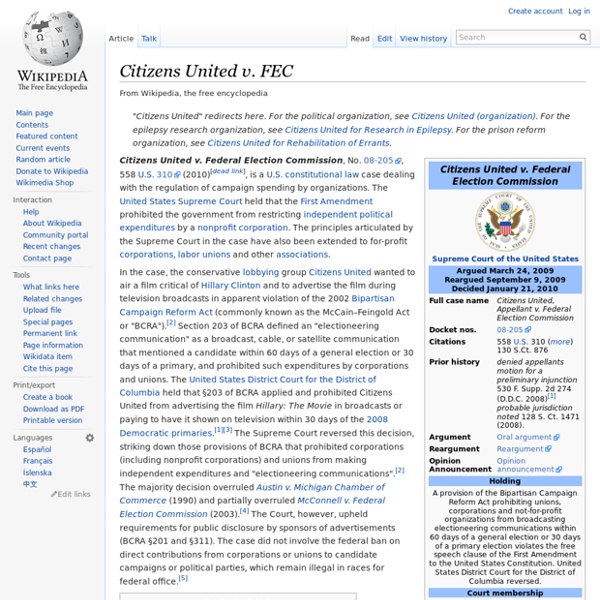

CITIZENS UNITED Court Opinion CITIZENS UNITED v . FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION appeal from the united states district court for the district of columbia No. 08–205. Argued March 24, 2009—Reargued September 9, 2009––Decided January 21, 2010 As amended by §203 of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA), federal law prohibits corporations and unions from using their general treasury funds to make independent expenditures for speech that is an “electioneering communication” or for speech that expressly advocates the election or defeat of a candidate. 2 U. In January 2008, appellant Citizens United, a nonprofit corporation, released a documentary (hereinafter Hillary ) critical of then-Senator Hillary Clinton, a candidate for her party’s Presidential nomination. Held: 1. (b) Thus, this case cannot be resolved on a narrower ground without chilling political speech, speech that is central to the First Amendment ’s meaning and purpose. 2. 3. Reversed in part, affirmed in part, and remanded.

Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act (ch. 27, 22 Stat. 403) of United States is a federal law established in 1883 that stipulated that government jobs should be awarded on the basis of merit.[1] The act provided selection of government employees by competitive exams,[1] rather than ties to politicians or political affiliation. It also made it illegal to fire or demote government employees for political reasons and prohibited soliciting campaign donations on Federal government property.[1] To enforce the merit system and the judicial system, the law also created the United States Civil Service Commission.[1] A crucial result was the shift of the parties to reliance on funding from business,[2] since they could no longer depend on patronage hopefuls. The law applied only to federal government jobs, not to the state and local jobs that were the basis for political machines. See also[edit] References[edit] Further reading[edit]

The Citizens United catastrophe The strongest case against judicial activism — against “legislating from the bench,” as former President George W. Bush liked to say — is that judges are not accountable for the new systems they put in place, whether by accident or design. The Citizens United justices were not required to think through the practical consequences of sweeping aside decades of work by legislators, going back to the passage of the landmark Tillman Act in 1907, who sought to prevent untoward influence-peddling and indirect bribery. If ever a court majority legislated from the bench (with Bush’s own appointees leading the way), it was the bunch that voted for Citizens United. Did a single justice in the majority even imagine a world of super PACs and phony corporations set up for the sole purpose of disguising a donor’s identity? “The appearance of influence or access, furthermore, will not cause the electorate to lose faith in our democracy.” ejdionne@washpost.com

United States Civil Service Commission The United States Civil Service Commission was a government agency of the federal government of the United States which was created to select employees of federal government on merit rather than relationships. In 1979, it was dissolved as part of the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978; the Office of Personnel Management and the Merit Systems Protection Board are the successor agencies. History[edit] In 1871, President Ulysses S. President Hayes' successor, James A. Pendleton law[edit] President Garfield's successor, President Chester A. Under the Commission Model, policy making and administrative powers were given to semi-independent commission rather than to the president. 1978 reorganization[edit] Effective January 1, 1978, functions of the commission were split between the Office of Personnel Management and the Merit Systems Protection Board under the provisions of Reorganization Plan No. 2 of 1978 (43 F.R. 36037, 92 Stat. 3783) and the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978. See also[edit]

Building a Democracy Movement - About Reclaim Democracy.org Reclaim Democracy! works to create a representative democracy with an actively participating public, where citizens don’t merely choose from a menu of options determined by elites, but play an active role in guiding the country and its political agenda. We believe that one’s influence should be a direct result of the quality of one’s ideas and the energy one puts into promoting these ideas, independent of wealth or status. We inspire citizens to make conscious choices about what role corporations should play in our society and to limit them to that role. What We Do Inform and Empower People Through presentations, articles, single-issue primers, and skill-building workshops are all part of our outreach work. Work for Constitution-level Change While we realize the necessity of defensive struggles against corporate harm to our communities, environment, human rights and more, we strive to think and work differently. Taking Action Who We Are

United States civil service In the United States, the federal civil service was established in 1871. The Federal Civil Service is defined as "all appointive positions in the executive, judicial, and legislative branches of the Government of the United States, except positions in the uniformed services." (5 U.S.C. § 2101).[1] In the early 19th century, positions in the federal government were held at the pleasure of the president—a person could be fired at any time. The spoils system meant that jobs were used to support the American political parties, though this was gradually changed by the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 and subsequent laws. According to the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), as of December 2011, there were approximately 2.79 million civil servants (civilian, i.e. non-uniformed) employed by the US Government.[3][4][5] (This includes executive, legislative and judicial branches of government. The U.S. civil service includes the Competitive service and the Excepted service.

Corporate personhood Corporate personhood is the legal notion that a corporation, separately from its associated human beings (like owners, managers, or employees), has at least some of the legal rights and responsibilities enjoyed by natural persons (physical humans).[1] In the United States and most countries, corporations have a right to enter into contracts with other parties and to sue or be sued in court in the same way as natural persons or unincorporated associations of persons. In a U.S. historical context, the phrase 'Corporate Personhood' refers to the ongoing legal debate over the extent to which rights traditionally associated with natural persons should also be afforded to corporations. A headnote issued by the Court Reporter in the 1886 Supreme Court case Santa Clara County v. In the United States[edit] As a matter of interpretation of the word "person" in the Fourteenth Amendment, U.S. courts have extended certain constitutional protections to corporations. In the 1886 case Santa Clara v.

New Mexico Legislature to Congress: Amend Against 'Citizens United' The Constitution of the United States can be amended in two formal ways: from the top down and from the bottom up. But New Mexico legislators have found a third way and, hopefully, other state legislators around the country will follow their lead. The US Constitution is traditionally amended via a process that begins with the endorsement of an amendment by the US House and US Senate and then the ratification of that amendment by the requisite three-fourths of state legislatures. That’s the top-down route. The bottom-up route begins when two-thirds of the state legislatures ask Congress to call a national convention to propose amendments. But what if a state legislature tells Congress to get moving? That’s what happened over the weekend, when the New Mexico state Senate voted 20-9 to approve Senate Memorial 3, which calls on the Congress to pass and send to the states for ratification a constitutional amendment to overturn the US Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United v.