Getting to Philosophy Clicking on the first link in the main text of a Wikipedia article, and then repeating the process for subsequent articles, usually eventually gets you to the Philosophy article. As of May 26, 2011, 94.52% of all articles in Wikipedia lead eventually to the article Philosophy. The remaining 100,000 (approx.) links to an article with no wikilinks or with links to pages that do not exist, or get stuck in loops (all three are equally probable).[1] The median link chain length to reach philosophy is 23. Crawl on Wikipedia from random article to Philosophy. There have been some theories on this phenomenon, with the most prevalent being the tendency for Wikipedia pages to move up a "classification chain." Applying the same steps to "Philosophy" itself and continuing onward, the user will return to "Philosophy" after 15 steps. Origins[edit] Following the chain consists of: See also[edit] References[edit] External links[edit]

Symphony of Science Categorization There are many categorization theories and techniques. In a broader historical view, however, three general approaches to categorization may be identified: Classical categorizationConceptual clusteringPrototype theory The classical view[edit] The classical Aristotelian view claims that categories are discrete entities characterized by a set of properties which are shared by their members. According to the classical view, categories should be clearly defined, mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. Conceptual clustering[edit] Conceptual clustering developed mainly during the 1980s, as a machine paradigm for unsupervised learning. Categorization tasks in which category labels are provided to the learner for certain objects are referred to as supervised classification, supervised learning, or concept learning. Conceptual clustering is closely related to fuzzy set theory, in which objects may belong to one or more groups, in varying degrees of fitness. Prototype Theory[edit]

User:Ilmari Karonen/First link An internet meme, originally discovered by a user of Reddit.com named pixelcrak [1] on April 13, 2011 and further popularized by xkcd [2], says that if you go to a random article on Wikipedia and keep clicking the first non-parenthesized link in the body text of each article you get, you'll always eventually end up at Philosophy. But is this really true? Or, rather, what is the probability of that actually happening? Having extracted the links (which took a while), I computed the limit cycles of the resulting iterated map and their basin sizes, i.e. the number of articles (excluding redirects) from which the iteration converged to each cycle. To summarize, the meme is indeed quite accurate: starting from a random Wikipedia article, the probability of ending up at the cycle which includes Philosophy is almost 95%.

Introducing The 2012 Alva Emerging Fellows Earlier this spring we launched our new Alva Emerging Fellowship program, providing cash grants to empower the next generation of inventors to take action on their ideas. With ideas spanning from iPhone apps to turbines, we received a truly inspiring range of proposals from young innovators striving to change the world for the better. Presented with our friends at GE, the Alva Emerging Fellowships support three innovators under 30 years of age who have demonstrated remarkable potential to create useful and innovative new products or services that will make an impact on the world. Without further ado, here are our three 2012 Alva Emerging Fellows!– Company:IPT Creators: Adam Booher w/ Ehsan Noursalehi and Jonathan Naber Innovation: Open Socket, an affordable prosthetic arm for people in developing countries. The Concept: Traditional efforts to improve the lives of people in developing countries often result in products that are designed for the “Other 90%”. www.supportipt.org www.onebeep.org

Alphabet of human thought The alphabet of human thought is a concept originally proposed by Gottfried Leibniz that provides a universal way to represent and analyze ideas and relationships, no matter how complicated, by breaking down their component pieces. All ideas are compounded from a very small number of simple ideas which can be represented by a unique "real" character.[1][2] René Descartes suggested that the lexicon of a universal language should consist of primitive elements. The systematic combination of these elements, according to syntactical rules, would generate "an infinity of different words". In the early 18th century, Leibniz outlined his characteristica universalis, an artificial language in which grammatical and logical structure would coincide, which would allow much reasoning to be reduced to calculation. See also[edit] References[edit] Jump up ^ Geiger, Richard A.; Rudzka-Ostyn, Brygida, eds. (1993).

All Roads Lead to “Philosophy” All Roads Lead to “Philosophy” There was an idea floating around that continuously following the first link of any Wikipedia article will eventually lead to “Philosophy.” 1 This sounded like a reasonable assertion, one that makes a certain amount of sense in retrospect: any description of something will typically use more general terms. Following that idea will eventually lead… somewhere. It also sounded like an idea that would be easily examinable with basic client-side scripting tools, using the Wikipedia API and a good graphing package. I still have a lot of tweaking to do but the results so far are pretty nice. Multiple titles can be added using a comma-separated list. There are some circumstances where a loop is detected up the chain. 1 See the tooltip by hovering over the cartoon at xkcd which is said to be the source of this observation.

Research Groups and Projects Each Media Lab faculty member and senior research scientist leads a research group that includes a number of graduate student researchers and often involves undergraduate researchers. How new technologies can help people better communicate, understand, and respond to affective information. How technology can be used to enhance human physical capability. How to create new ways to capture and share visual information. How new strategies for architectural design, mobility systems, and networked intelligence can make possible dynamic, evolving places that respond to the complexities of life.

Bloom's Taxonomy Bloom's wheel, according to the Bloom's verbs and matching assessment types. The verbs are intended to be feasible and measurable. Bloom's taxonomy is a classification of learning objectives within education. It is named for Benjamin Bloom, who chaired the committee of educators that devised the taxonomy, and who also edited the first volume of the standard text, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Bloom's taxonomy refers to a classification of the different objectives that educators set for students (learning objectives). Bloom's taxonomy is considered to be a foundational and essential element within the education community. History[edit] Although named after Bloom, the publication of Taxonomy of Educational Objectives followed a series of conferences from 1949 to 1953, which were designed to improve communication between educators on the design of curricula and examinations. Cognitive[edit] Knowledge[edit] Comprehension[edit] Application[edit]

Heterotopia (space) Heterotopia is a concept in human geography elaborated by philosopher Michel Foucault to describe places and spaces that function in non-hegemonic conditions. These are spaces of otherness, which are neither here nor there, that are simultaneously physical and mental, such as the space of a phone call or the moment when you see yourself in the mirror. A utopia is an idea or an image that is not real but represents a perfected version of society, such as Thomas More’s book or Le Corbusier’s drawings. Foucault uses the idea of a mirror as a metaphor for the duality and contradictions, the reality and the unreality of utopian projects. Foucault articulates several possible types of heterotopia or spaces that exhibit dual meanings: A ‘crisis heterotopia’ is a separate space like a boarding school or a motel room where activities like coming of age or a honeymoon take place out of sight.

Marcel Roland Un article de Wikipédia, l'encyclopédie libre. Le Presqu'homme, roman de Marcel Roland publié en 1908 Marcel Roland (1879-1955) est un écrivain français, célèbre par ses ouvrages de vulgarisation scientifique publiés au Mercure de France. Il fut en outre romancier et conteur pour les journaux. Il est connu des amateurs d'anticipation ancienne pour ses ouvrages : Le Presqu'homme (1908)Le Déluge futur (1910)La Conquête d'Anthar (1913, prix Excelsior)Le Faiseur d'or (1913-1914)Quand le phare s'alluma (1921-1922)Osmant le rajeunisseur (1925). Il a également publié des nouvelles : « Sous la lumière inconnue », dans le journal Le Miroir (n° 52, 23 mars 1913), « Le Serpent fantôme » et « L'Échelon » (Journal Le Rocambole n° 6), ainsi que plusieurs contes, de 1911 à 1915. Parmi ses œuvres naturalistes, il faut citer : 1) Vie et Mort des Insectes, 19362) La Grande Leçon des petites bêtes, 1938.3) La féerie du microscope.4) Mimétisme et instinct de défense, 1941.5) Amour, harmonie, beauté

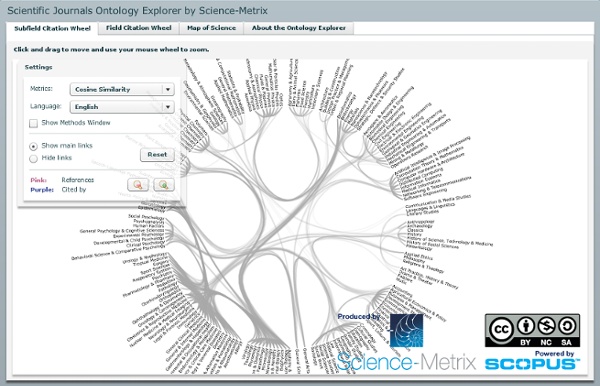

Listing of 185 Ontology Building Tools At the beginning of this year Structured Dynamics assembled a listing of ontology building tools at the request of a client. That listing was presented as The Sweet Compendium of Ontology Building Tools. Now, again because of some client and internal work, we have researched the space again and updated the listing [1]. All new tools are marked with <New> (new only means newly discovered; some had yet to be discovered in the prior listing). Comprehensive Ontology Tools Altova SemanticWorks is a visual RDF and OWL editor that auto-generates RDF/XML or nTriples based on visual ontology design. Not Apparently in Active Use Adaptiva is a user-centred ontology building environment, based on using multiple strategies to construct an ontology, minimising user input by using adaptive information extractionExteca is an ontology-based technology written in Java for high-quality knowledge management and document categorisation, including entity extraction. Vocabulary Prompting Tools Ontology Editing

The 50 most interesting articles on Wikipedia « Copybot Deep in the bowels of the internet, I came across an exhaustive list of interesting Wikipedia articles by Ray Cadaster. It’s brilliant reading when you’re bored, so I got his permission to post the top 50 here. Bookmark it, start reading, and become that person who’s always full of fascinating stuff you never knew about. The top 50 Wikipedia articles by interestingness 1. *Copybot is not responsible for the hours and hours that disappeared while you were exploring this list. Edit: If you enjoyed this list, I’ve since posted 50 more of Wikipedia’s most interesting articles. Like this: Like Loading... Related Picking flicks About six months ago, it dawned on me that whenever someone asked me if I'd seen a particular film, my answer was almost invariably no. In "Copybot articles"