From Skedaddle to Selfie: Words of the Generations by Allan Metcalf – review Previously, Allan Metcalf, a professor of English at MacMurray College in Jacksonville, Illinois, has written a whole book devoted to “America’s greatest word”: OK (or “K”, as my 16-year-old daughter likes to “abbrev” it, presumably to save energy in her texting thumb). This new slimmer volume goes at the etymology of American slang from a different direction; it sets out, somewhat haphazardly, to define the character of generations from the words they coin. OK itself was by this reckoning a “product of the transcendental generation”, though you can’t quite imagine Thoreau having much use for it as he contemplated Walden Pond. It was invented in 1839 by Charles Gordon Greene, editor of the Boston Morning Post, in a story full of other “humorous contractions” such as RTBS (remains to be seen). Correctness, you are reminded, is the enemy of slang, trying to prevent underage neologisms slipping into the speakeasy lexicon and lowering the tone.

How the internet is killing off silent letters Professor David Crystal says people drop letters when typing them into search engines He says the internet will influence changes in spelling in the future Academic labels the 'h' in rhubarb as 'illogical' By Daily Mail Reporter Published: 08:29 GMT, 2 June 2013 | Updated: 06:40 GMT, 3 June 2013 David Crystal, professor of linguistics of Bangor University, explained how people are dropping letters when typing words into search engines Common misspellings of English words could be acceptable within a few years because they are used online, a linguist has said. ‘Rhubarb’ could change to ‘rubarb’, ‘receipt’ to ‘receit’ and ‘necessary’ to ‘neccesary’. Simpler online forms of ‘irritating’ complex words are starting to affect mainstream usage, linguistics professor David Crystal told the Hay Literary Festival. He started monitoring the word ‘rhubarb’ ten years ago by typing the correct spelling into a search engine, then the error ‘rubarb’. ‘Rhubarb is still the dominant one by a factor of 50.

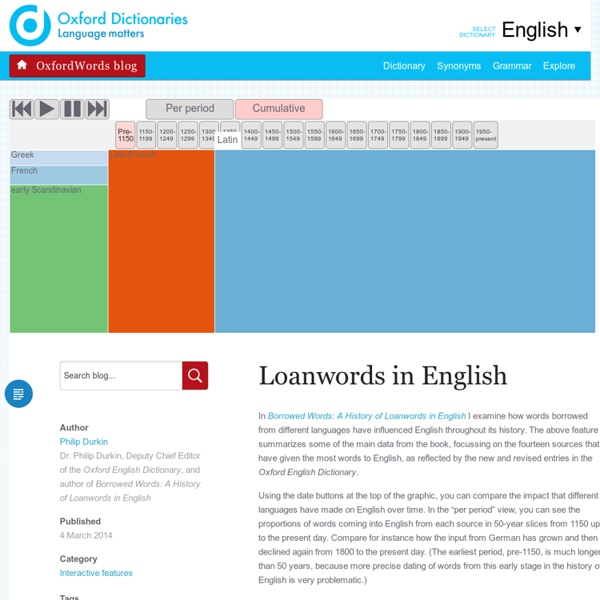

Creating New Words For New Needs I'm continually astounded at the ability of the English language to furnish new words for new needs. When innovative technologies, trends or ideas expose gaps in the front line of our vocabulary, we quickly send in fresh soldiers — new words! — to plug the holes. People are taking snapshots of themselves with their cellphones? But what astounds me even more is that English has failed to generate new words to describe other significant phenomena or simply to fill basic linguistic functions. Why, for instance, don't we have a general term to describe an adult in a loving relationship with someone else? In all fairness, you can't say we haven't tried to come up with a better term. Similarly, people have been trying for centuries to devise a gender-neutral, third-person singular pronoun to replace the clunky "he or she/him or her" construction. Guess what? And then there's the question of what to call the past decade.

100 words that define the First World War The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) World War I timeline shows some of the ways in which the events of the First World War left their mark on the English language. For example, the wet and muddy conditions of the first winter of trench warfare were evoked in the term Flanders mud (November 1914), while trench boots and trench coats (both December 1914) were invented to cope with these conditions. By early 1915 the physical and psychological effects of trench warfare were being felt: both trench foot and shell shock are first recorded in January 1915. One linguistically important event was the involvement of Australian and New Zealand troops at Gallipoli (1915), which led to the coinage or spread of terms such as Anzac (April 1915), Aussie (1915 as a noun), and the Anzacs’ affectionate term for a British soldier, choom (June 1916). The timeline also highlights developments in military technology, such as the introduction of the tank in 1916.

Crying with laughter: how we learned how to speak emoji | Technology The Oxford dictionary has announced its word of the year. It’s spelled ... Actually, it isn’t spelled at all, because it contains no letters, just a pair of symmetrical eyebrows, eyes, big gloopy tears, and a broad monotooth grin. That’s right, the word of the year is the “face with tears of joy” emoji. But that’s not a word at all! “The fact that English alone is proving insufficient to meet the needs of 21st-century digital communication is a huge shift,” says Grathwohl. Three or four years ago, Oxford Dictionaries’ announcement would have been subversive, but now it seems a reasonable reflection of the way that language is shifting. In fact, emojis have their own version of the Oxford dictionary. Anyone can suggest an emoji, says Vyvyan Evans, a professor in linguistics at Bangor University, who has spent the past year studying emojis. But how far do emojis function as a language in their own right? It was in Japan, in the late 1990s, that emoji were born. A guide by Sara Ilyas

Language change in spoken English Influenced by others Language also changes very subtly whenever speakers come into contact with each other. No two individuals speak identically: people from different geographical places clearly speak differently, but even within the same small community there are variations according to a speaker’s age, gender, ethnicity and social and educational background. Through our interactions with these different speakers, we encounter new words, expressions and pronunciations and integrate them into our own speech. Listen to these recordings in this section, which illustrate important, recent changes in spoken English. “we couldn’t listen to the latest tunes because we hadn’t a wireless” Attitudes to language change some method should be thought on for ascertaining and fixing our language for ever (...) it is better a language should not be wholly perfect, than that it should be perpetually changing Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels, wrote these words in 1712.

What will the English language be like in 100 years? Simon Horobin, University of Oxford One way of predicting the future is to look back at the past. The global role English plays today as a lingua franca – used as a means of communication by speakers of different languages – has parallels in the Latin of pre-modern Europe. Having been spread by the success of the Roman Empire, Classical Latin was kept alive as a standard written medium throughout Europe long after the fall of Rome. Similar developments may be traced today in the use of English around the globe, especially in countries where it functions as a second language. Despite the Singaporean government's attempts to promote the use of Standard British English through the Speak Good English Movement, the mixed language known as "Singlish" remains the variety spoken on the street and in the home. Spanglish, a mixture of English and Spanish, is the native tongue of millions of speakers in the United States, suggesting that this variety is emerging as a language in its own right.

Sexuality: Guide to new world of greysexual, aromantic and questioning Straight people, I don’t know if you realise this but you talk about yourselves a lot. What with your marriages and children and holding hands in the street, your sexuality is on display all the time. We can move on. Lesbian Ellen Degeneres with her Hollywood star Photo: Reuters Women who like women. Famous lesbians: Sappho and ‘the Ellens’ - Degeneres and Page. Gay Like being a lesbian except you’re statistically likely to earn more and less likely to be judged on your appearance. Famous gay men: Stephen Fry, Mark Gatiss, Oscar Wilde Bisexual Alan Cumming Photo: REX/c.Music Box Films/Everett No, it doesn’t mean you can’t make up your mind. Famous bi people: Alan Cumming, Saffron Burrowes Queer This is a tricky one. Questioning Here’s the big secret – it’s OK not to make up your mind! Asexual Benedict Cumberbatch as Sherlock Holmes Photo: BBC/Hartswood If sexual orientation was a menu, asexuals wouldn’t even be in the restaurant. Famous asexuals: Sherlock Holmes, arguably. Aromantic Greysexual

Do you really know what that word means? Caitlin Dewey discovers 24 words that mean totally different things now than they did pre-internet. Technological change, as we know very well, tends to provoke linguistic and cultural change, too. It's the reason why, several times a year, dictionaries trumpet the addition of new and typically very trendy words. But more interesting than the new words, are the old words that have been given new meanings: words such as "cloud" and "tablet" and "catfish", with very long pre-internet histories. Anyway, this is all a very long way of saying that dictionary.com's 20th birthday is more interesting than most. On one hand, the list shows how technology has shaped language over time. But it also shows how language has shaped technology - or, at least, our technological understandings and paradigms. Bump Then: To encounter something that is an obstacle or hindrance.Now: To move an online post or thread to the top of the reverse chronological list by adding a new comment or post to the thread. Block

Word Evolution: 11 Words that Mean Something Different to Entrepreneurs | Chester Goad, Ed.D. Have you ever really thought about how terms take on new meaning over time? When I was a kid, the word "sick" actually meant sick. Today "sick" can also mean "amazing". Words and phrases evolve over time--especially in the business world. Hustle © velusariot - Fotolia.com Hustle: No longer just a groovy dance, "to hustle" means to work hard. Side hustle: Many emerging entrepreneurs still have a day job but they have hustles outside their typical 9-5, so they have what's called a "side hustle". Mastermind © antonbrand - Fotolia.com Mastermind: Nope, I'm not talking about evil villains here. Branding © Janis Tremper - Fotolia.com Branding: Put away those branding irons. Hack © katalinks - Fotolia.com Hack: No traumatic bludgeoning thriller here. Toolbox Photo by Peter Griffin Toolbox: For some, the word toolbox might conjure up literal images of their grandpa's old wooden toolbox or their parent's tool chest. Thought Leader © fakegraphic - Fotolia.com Silo Photo by Linnaea Mallette Social Proof Tribe

Scouring the Web to Make New Words ‘Lookupable’ A couple of weeks ago, two of my New York Times colleagues chronicled digital culture trends that are so newish and niche-y that conventional English dictionaries don’t yet include words for either of them. In an article on Sept. 20, Stephanie Rosenbloom, a travel columnist, reviewed flight apps that try to perfect “farecasting” — that is, she explained, the art of “predicting the best date to buy a ticket” to obtain the lowest fares. That same day Jenna Wortham, a columnist for The Times Magazine, described a phenomenon she called “technomysticism,” in which Internet users embrace medieval beliefs, spells and charms. These word coinages may be too fresh — and too little used for now — to be of immediate interest to major English dictionaries. But Erin McKean, a lexicographer with an egalitarian approach to language, thinks “madeupical” words such as these deserve to be documented. Ms. Photo “We really believe that every word should be lookupable,” Ms. Ms. Ms. Mr.