http://www.straight.com/node/428331

Former residential school teacher opens up Sometimes, in this business, a story sticks with you long after it’s gone to air. In 2008, when Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission into Indian Residential Schools (TRC) was first getting started, I did a remarkable interview while guest hosting The Current on CBC Radio. It’s not often we hear from former teachers of Indian residential schools, so I was naturally intrigued by my guest Florence Kaefer, who taught at just such a school in Norway House, Manitoba, in the 1950s. But something else made the interview truly memorable. Florence, on the line from Vancouver Island, was joined by one of her former students, Edward Gamblin, calling in from northern Manitoba.

Residential School Money: Has It Helped Survivors Heal? The Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF) has just released The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement’s Common Experience Payment and Healing: A Qualitative Study Exploring Impacts on Recipients. (PDF of study available here.) The Common Experience Payment (CEP) is a component of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and is intended to monetarily recognize and compensate the experiences of former Residential School students. The study — a follow-up to the 2007 AHF report, Lump Sum Compensation Payments Research Project — builds upon 281 interviews with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Residential School Survivors. (Full disclosure: my mother and my friend Rick Harp co-authored the Lump Sum report.)

Last residential school in Canada From 1861 until the year the last school closed, over 150,000 Aboriginal children were removed from their homes –- often forcibly by the RCMP -- and sent to residential schools, where they were prevented from speaking their own languages and practicing their cultures. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimates that 80,000 residential school survivors are living in Canada today. Around 90 per cent experienced severe emotional, physical, or sexual abuse while in these government-funded, church-run schools. From Sept. 16 – 22, Vancouver hosts Reconciliation Week, a series of inclusive events that includes the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's BC National Event, and Reconciliation Canada events such as the Walk for Reconciliation. Reconciliation Canada is a multi-faith, multi-cultural organization. Under the leadership of Chief Dr.

Jallianwala Bagh massacre The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, also known as the Amritsar massacre, was a seminal event in the British rule of India. On 13 April 1919, a crowd of non-violent protesters, along with Baishakhi pilgrims, had gathered in the Jallianwala Bagh garden in Amritsar, Punjab to protest the arrest of two leaders despite a curfew which had been recently declared.[1] On the orders of Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, the army fired on the crowd for ten minutes, directing their bullets largely towards the few open gates through which people were trying to run out. The dead numbered between 370 and 1,000, or possibly more. This "brutality stunned the entire nation",[2] resulting in a "wrenching loss of faith" of the general public in the intentions of Britain.[3] The ineffective inquiry and the initial accolades for Dyer by the House of Lords fuelled widespread anger, leading to the Non-co-operation movement of 1920–22.[4]

For residential school survivors I live in fear of the dark because of the residential school. Sainty Morris was play-wrestling with his best friend when they got caught. The residential school priests forced the two boys to beat each other bloody. Another time, Morris helped a younger student hide a puppy. When they were caught — again— the priests made them drown the puppy in a sack. And no matter how minor the infraction, the priests locked Morris in a dark room without food or water for as long as 15 hours. The Wildly Depressing History of Canadian Residential Schools Photo from a residential school off of Onion Lake in Ontario. During the mid 1800’s Canada’s colonization was chugging along with the industrial age, and the thinkers of the day were turning their brainpower towards the pesky task of how to deal with the “Indian Problem.” In 1841, Herman Charles Merivale, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies (who doesn’t look like he would be a bad guy to smoke cigars and sip sherry with), established and executed a concoction of his four policies on the subject: Extermination, slavery, insulation and assimilation. All of these were wrapped tidily up in the Residential School system. Testifying in Fort Albany, a former female student at St. Anne’s put it like this:

What are residential schools What is a residential school? In the 19th century, the Canadian government believed it was responsible for educating and caring for aboriginal people in Canada. It thought their best chance for success was to learn English and adopt Christianity and Canadian customs. Ideally, they would pass their adopted lifestyle on to their children, and native traditions would diminish, or be completely abolished in a few generations. The Canadian government developed a policy called "aggressive assimilation" to be taught at church-run, government-funded industrial schools, later called residential schools. Nicolae Ceaușescu Nicolae Ceaușescu (/ˌniːkɔːˈlaɪ tʃaʊˈʃɛskuː/[1] NEE-koh-LY chow-SHES-koo; Romanian: [nikoˈla.e t͡ʃe̯a.uˈʃesku]; 26 January 1918[2] – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian communist politician. He was General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and as such was the country's second and last Communist leader. He was also the country's head of state from 1967 to 1989. A member of the Romanian Communist youth movement, Ceaușescu rose up through the ranks of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej's Socialist government and, upon the death of Gheorghiu-Dej in 1965, he succeeded to the leadership of Romania’s Communist Party as General Secretary. After a brief period of relatively moderate rule, Ceaușescu's regime became increasingly brutal and repressive. By some accounts, his rule was the most rigidly Stalinist in the Soviet bloc.[3] He maintained controls over speech and the media that were very strict even by Soviet-bloc standards, and internal dissent was not tolerated.

Reconciliation a monetary and emotional battle for residential school survivor Mavis Jeffries would do anything to get to Vancouver, but it won’t be easy. Coming to Vancouver means coming to terms with a lifetime of sadness for the residential school survivor. She’s been combing Facebook looking for a ride and learning to surf the net on a cellphone to try and find a way to get to here by Wednesday so she can walk with her people at the Truth and Reconciliation gathering, share her story and hear others. She’s even been selling bannock by the side of the highway in Gitsegukla, near Hazelton, to scrape together the money for a bus ticket. For Jeffries, who survives by hunting, fishing and picking blueberries, and who clothes her family on $5-a-bag clothing from a thrift store, a trip to Vancouver is an extravagence beyond her wildest dreams.

Happiness in Res. Schools J. FRASER FIELD While the horror of what occurred all to often needs to be brought out, such a one-sided and simplistic characterization constitutes a distortion of the truth and an injustice to the many, and there were many, who served the native people in good faith and with much love. Painting all residential schools as dysfunctional places of abuse and making them a collective scapegoat for the social problems which continue to plague the native people of Canada will not solve these problems, nor does it do justice to the many who worked tirelessly for the betterment of native children (Schools aimed to “kill the Indian in the child,” Nov. 22).

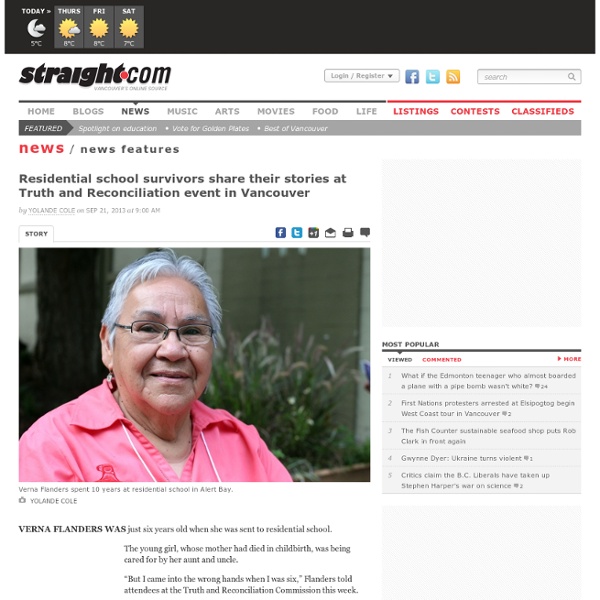

This article is very changing, because a lot of the victims share their storys and what they had to go through to in these schools to be able to survive. Many survivors share that they had losed a great part of their childhod meaning that they could not play anymore but they only had school and it was a long time before seeing theur parents due to the fact that they were attending these schools. by ionescuhanes Oct 31

In this link, the lady explains how she got treated in the residential schools. It very brutal because she got abused for years as a child. In sweetgrass basket, Sarah and Mattie were explaining how they were getting treated during the whole book. Some teacher would abuse them less but there were some that were very strict and cruel. by shaynuswardus Oct 31

I believe that these survivors are truly heroes, first because I believe that nobody should deal with this kind of abuse and violence. Also after being abused for years as a child they found the courage to relive these events by telling them to everybody, and trying to ware awareness. Alot of people are uneducated on the past of Canada regarding aboriginals and residential schools, and how some Native Americans are now scared for life. by coteb Oct 29

This article is very disturbing, because many survivors share their story and what they had to fo through to survive. Many survivors share that they lost all of their childhod due to the fact that they were attending these schools. by marsolaismartel Oct 25

In this article, residential school survivors share their stories of what is was like to be in the residential schools. They were taken away from their families at a very young age and experienced a lot of trauma due to these schools. This article is relevant and is also very emotional because the stories included are tragic and unfortunately all true. by scarpaleggiamaiorino Oct 24

We think that this source is realible, it has many quotes and is a very great example of a real residential school survivor story. It demonstrates the scars these aboriginal school survivors have and how they feel and live after they leave the school. We think it's a tragic part of our history, the woman who felt loneliness is a hero to us and many others. She helps the awareness of residential school to students and she encourages the other suvivors to talk about their experiences too. It's horrendous, to know what these schools have done to these Idians for example Morris can't even sleep in the dark because it reminds him of these awful memories he dealt with while he attended his residential school. by chenglaitung Oct 24

Comment: This source brings us good examples of real Residential Schools survivors stories. From a very young age, they whent trough physical, psychological and emotional abuse.These events are still haunting them in their lives today and these memories are engraved in their minds forever. by serhanboulet Oct 22

This source brings out alot of emotions as we learn more about this woman's story. In this article, we can learn more about how the students lived and how they were psychologically and physically harmed. We also realise that during all the years they spent in resedential schools, the students missed out on their youths and once they we're back, it didn't feel like home anymore. by cotegiroux Oct 21

This article is a good source because it reviews in details the horrible stories of the survivors of the residential schools. They went thru intense emotional, psychological as well as physical scarring. And all this from a very young age up until now because the scarring is still somewhere deep in their memories. However, it is good that some survivors are willing to share these stories for the public to see and understand the horrors of residential schools. by biellowener Oct 18

Good source because we can read about acctual peple who has been abused by the residential schools, we have true witnesses witness. by lamarresebire Oct 17

this article shows us in great detail the horrid stories of survivors of some residential school were forced to live in. we learned that theses people were emotionally and sexually abused almost everyday for the most stupid reasons you could posibly think of. They were forced to forget their homes and families, their culture and religion everything that remiended them of their past. They lived in horrible cercomstances and most of these survivors were stripped of their childhood because some were taken at such a young age and now they are scared with alll the shame they had to take in for such a long perieod of time. by tousignanttchekilk Oct 17

This source is very emotionally charged but at the same time very interesting because the residential school survivor gives the truth about what she went through at that time and after, when the government didn’t help her, which is very informative. The story of the survivor tells a lot about what went on behind the residential school walls. by wangdulong Oct 15

We chose this article because this women’s inspirational story warmed our hearts. In general, these survivors are heroes. They survived through the cruelty and the difficult obstacles. It gives us a clear perspective of what they went through at the Residential schools. We now clearly understand how this traumatizing experience touched many lives. by grigorislarose Oct 15

Many native children were torn from their homes and were forced to attend the residential schools. It was not only required that they should learn an entirely new culture, they were forced to forget their own. Many experienced horrible situations at these schools and countless didn’t live to tell the world what happened. by bertoia.bobotis.dufresne. Oct 8

This lady tells her children the story about attending the residentials schools, she mentions that she was taken away from her parents at a young age, she felt alone and had no one to rely on. by mohsen.chartier Oct 8