Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Background[edit] Early attempts at stimulation of the brain using a magnetic field included those, in 1910, of Silvanus P. Thompson in London.[2] The principle of inductive brain stimulation with eddy currents has been noted since the 20th century. The first successful TMS study was performed in 1985 by Anthony Barker and his colleagues at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield, England.[3] Its earliest application demonstrated conduction of nerve impulses from the motor cortex to the spinal cord, stimulating muscle contractions in the hand. As compared to the previous method of transcranial stimulation proposed by Merton and Morton in 1980[4] in which direct electrical current was applied to the scalp, the use of electromagnets greatly reduced the discomfort of the procedure, and allowed mapping of the cerebral cortex and its connections. Theory[edit]

Eidetic memory -photographic memory

Overview[edit] The ability to recall images in great detail for several minutes is found in early childhood (between 2% and 10% of that age group) and is unconnected with the person's intelligence level.[citation needed] Like other memories, they are often subject to unintended alterations. The ability usually begins to fade after the age of six years, perhaps as growing vocal skills alter the memory process.[2][3] A few adults have had phenomenal memories (not necessarily of images), but their abilities are also unconnected with their intelligence levels and tend to be highly specialized. In extreme cases, like those of Solomon Shereshevsky and Kim Peek, memory skills can actually hinder social skills.[4]

Cognition

Cognition is a faculty for the processing of information, applying knowledge, and changing preferences. Cognition, or cognitive processes, can be natural or artificial, conscious or unconscious.[4] These processes are analyzed from different perspectives within different contexts, notably in the fields of linguistics, anesthesia, neuroscience, psychiatry, psychology, philosophy, anthropology, systemics, and computer science.[5][page needed] Within psychology or philosophy, the concept of cognition is closely related to abstract concepts such as mind, intelligence. It encompasses the mental functions, mental processes (thoughts), and states of intelligent entities (humans, collaborative groups, human organizations, highly autonomous machines, and artificial intelligences).[3] Etymology[edit]

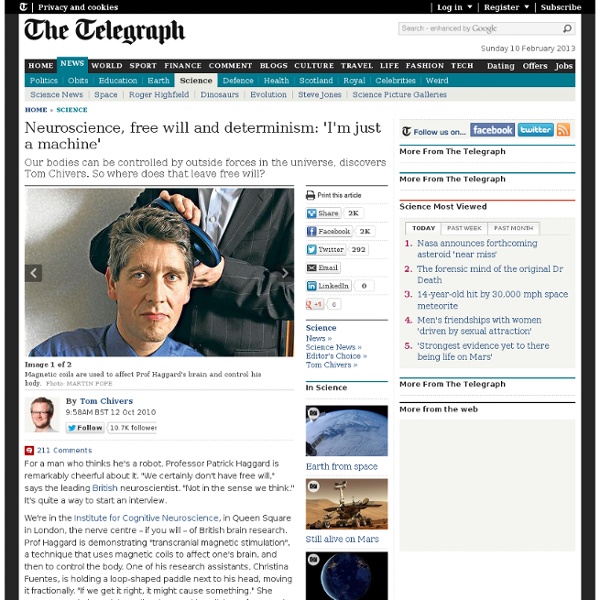

Learn more quickly by transcranial magnetic brain stimulation, study in rats suggests

What sounds like science fiction is actually possible: thanks to magnetic stimulation, the activity of certain brain nerve cells can be deliberately influenced. What happens in the brain in this context has been unclear up to now. Medical experts from Bochum under the leadership of Prof. Dr. Klaus Funke (Department of Neurophysiology) have now shown that various stimulus patterns changed the activity of distinct neuronal cell types.

Berkeley on Biphasic Sleep

If you see a student dozing in the library or a co-worker catching 40 winks in her cubicle, don’t roll your eyes. New research from the University of California, Berkeley, shows that an hour’s nap can dramatically boost and restore your brain power. Indeed, the findings suggest that a biphasic sleep schedule not only refreshes the mind, but can make you smarter. Students who napped (green column) did markedly better in memorizing tests than their no-nap counterparts.

Cognitive bias

Systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment Although it may seem like such misperceptions would be aberrations, biases can help humans find commonalities and shortcuts to assist in the navigation of common situations in life.[5] Some cognitive biases are presumably adaptive. Cognitive biases may lead to more effective actions in a given context.[6] Furthermore, allowing cognitive biases enables faster decisions which can be desirable when timeliness is more valuable than accuracy, as illustrated in heuristics.[7] Other cognitive biases are a "by-product" of human processing limitations,[1] resulting from a lack of appropriate mental mechanisms (bounded rationality), impact of individual's constitution and biological state (see embodied cognition), or simply from a limited capacity for information processing.[8][9]

Magnetic Mind Control

How Does the Brain Work? PBS Airdate: September 14, 2011 NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Hi, I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your host for NOVA scienceNOW, where this season, we're asking six big questions. On this episode: How Does the Brain Work?

The lost art of total recall

A few middle-aged couples are chatting at a dinner party when one husband, Harry, starts talking enthusiastically about a new restaurant he has just visited with his wife. What's its name, demands a friend. Harry looks blank. There is an awkward pause.