Adaptive Artificial Intelligence Inc.-Research Real A.I. Intro

Introduction This is a book chapter written by Peter Voss and published in "Artificial General Intelligence" - Goertzel, Ben; Pennachin, Cassio (Eds). Written in 2002, this describes the foundation of our project: the low level, conceptual underpinnings that remain an important functioning part of our current more advanced research. Peter Voss is an entrepreneur with a background in electronics, computer systems, software, and management. Book Chapter also available as Word 2000 (.doc) Essentials of General Intelligence: The direct path to AGI 1. This paper explores the concept of 'artificial general intelligence' (AGI) - its nature, importance, and how best to achieve it. The idea of 'general intelligence' is quite controversial; I do not substantially engage this debate here but rather take the existence of such non domain-specific abilities as a given (Gottfredson 1998). 2. · Adaptive - Learning is cumulative, integrative, contextual and adjusts to changing goals and environments. 1.

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) • TheNanoAge.com

"Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly after, the human era will be ended."- Vernor Vinge, NASA Vision-21 Symposium, 1993 Defined as, "the intelligence of a machine that can successfully perform any intellectual task that a human being can," Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), or "Strong AI" has been the goal and dream of AI researchers since the mid 1950s. Most researchers today choose to focus on more manageable sub problems, also known as Weak AI, Narrow AI, or Applied AI, which they hope may eventually be combined to achieve Strong AI, using an integrated approach. Exponential growth in computing power (known as Moore's Law) is the driving force behind AGI. Due, once again, to the exponential nature of technological acceleration, once achieved, AGI will rapidly evolve into a form that exceeds the intelligence of the smartest human being. According to Justin Rattner; Intel's CTO,

amazon

Artificial Intelligence

Defining Artificial Intelligence The phrase “Artificial Intelligence” was first coined by John McCarthy four decades ago. One representative definition is pivoted around comparing intelligent machines with human beings. Another definition is concerned with the performance of machines which historically have been judged to lie within the domain of intelligence. Yet none of these definitions have been universally accepted, probably because the reference of the word “intelligence” which is an immeasurable quantity. With all this a common questions arises: Does rational thinking and acting include all characteristics of an intelligent system? If so, how does it represent behavioral intelligence such as learning, perception and planning? If we think a little, a system capable of reasoning would be a successful planner. With all this we may conclude that a machine that lacks of perception cannot learn, therefore cannot acquire knowledge. General Problem Solving Approaches in AI Begin AI Algorithm

Artificial Intelligence: Tracking the evolution of the machine age

Apr 21, 2011, 07.21am IST Peter Norvig Forty years ago this December, US President Nixon declared a war on cancer, pledging a "total national commitment" to conquering the disease. Fifty years ago, US President Kennedy declared a space race, promising to land a man safely on the moon before the end of the decade. And 54 years ago, Artificial Intelligence pioneer Herbert Simon declared that "there are now in the world machines that think" and predicted that a computer would be world chess champion within 10 years. How have these bold efforts fared? The Apollo programme succeeded, but it also marked the end of progress — no human has traveled more than 400 miles away from Earth since 1975. The same has been true for AI research. Your Microsoft Kinect recognizes motion and gestures well enough that you don't need a video game controller anymore. By contrast, teaching computers to deal with uncertainty, such as identifying an object in a blurry picture, proved more difficult.

Why Did Google Pay $400 Million for DeepMind?

How much are a dozen deep-learning researchers worth? Apparently, more than $400 million. This week, Google reportedly paid that much to acquire DeepMind Technologies, a startup based in London that had one of the biggest concentrations of researchers anywhere working on deep learning, a relatively new field of artificial intelligence research that aims to achieve tasks like recognizing faces in video or words in human speech (see “Deep Learning”). The acquisition, aimed at adding skilled experts rather than specific products, marks an acceleration in efforts by Google, Facebook, and other Internet firms to monopolize the biggest brains in artificial intelligence research. Companies like Google expect deep learning to help them create new types of products that can understand and learn from the images, text, and video clogging the Web. As advanced machine learning transitions from a primarily scientific pursuit to one with high industrial importance, Google’s bench is probably deepest.

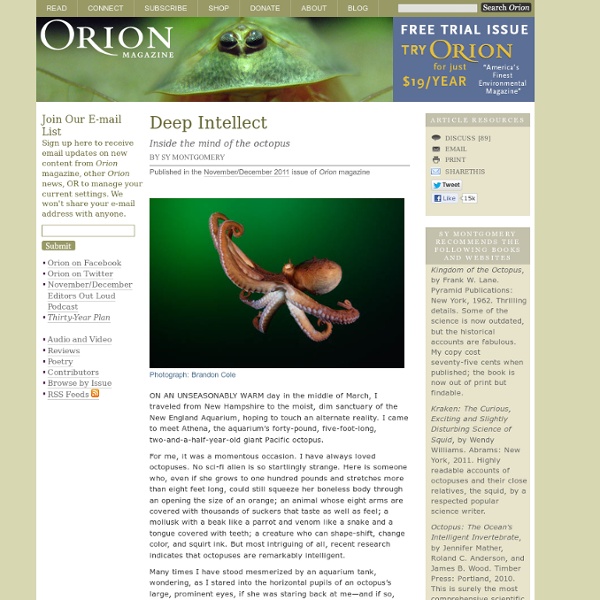

octopus challenes our understanding of consciousness itself by electronics Nov 3