Roman Influence on Western Civilization | Philosophy Western civilization is what is presently called modern or contemporary society that mainly comprises Western Europe and North America. It is believed that civilization came in through the influence of ancient cultures the two main ones being Greek and Roman. The influence by Greece was mainly by their golden age and Rome with its great Empire and Republic. This means that civilization has been in place for centuries. Roman Influence on Western Civilization The Roman greatness was marked by their willingness to receive other peoples ideas for their own purposes. Christianity played a key role in civilization and the culture that is still in place in the western civilization. The roads were primarily meant to transport the Roman troops to places that experienced problems, but they served to promote trade and the arrival of Italian merchants into the towns of the western provinces. The language of the Roman was Latin, italic language that relied little on order of words.

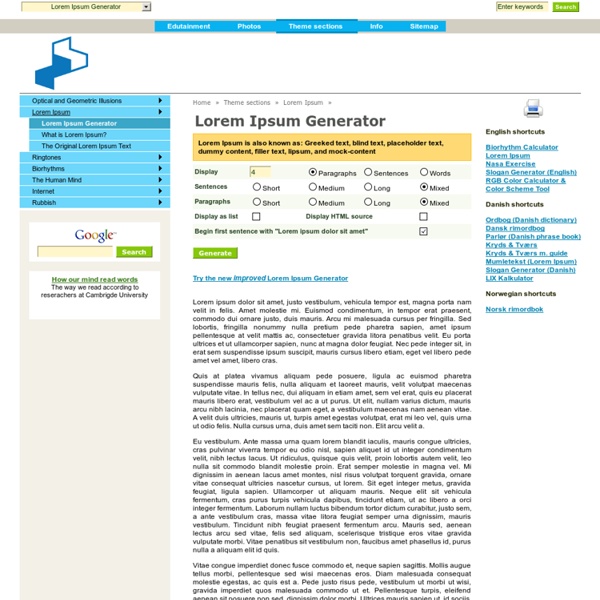

|| Dummy Text Generator | Lorem ipsum for webdesigners || Philosophy: Latin terms with English translations It would is a nearly impossible task to come up with a comprehensive dictionary of Latin terms used in any particular setting. Philosophical Latin is highly technical and individual philosophers often adapted existing terms for their own needs. Still, it is my hope that this wordlist will be useful to someone just starting to read philosophic works in the original Latin. BEATITUDO - beatitude, blessedness, happiness BEATUS - blessed, happy BENEDICTUM - blessed BENEFICIUM - favor, boon BENEVOLENTIA - benevolence, good will, kindness, friendship BONUM - (moral) good, kindness, benefit, prosperity, property, advantage GENERATIO - generation GENUS - genus GENERALISSIMUM - generalissimum, most general genus GLOSSA (GLOSSEMA) - gloss, obsolete or foreign word that requires explanation HABERE - to have, condition, state HABITUDO - condition, aptitude, relation, respect, capacity for something HABITUS - condition, habit, character HAECCEITAS - haecceity, hecceity, “thisness”

Lorem ipsum „Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, …“ ist ein Blindtext, der nichts bedeuten soll, sondern als Platzhalter im Layout verwendet wird, um einen Eindruck vom fertigen Dokument zu erhalten. Die Verteilung der Buchstaben und der Wortlängen des pseudo-lateinischen Textes entspricht in etwa der natürlichen lateinischen Sprache. Der Text ist absichtlich unverständlich, damit der Betrachter nicht durch den Inhalt abgelenkt wird. Historische Herkunft[Bearbeiten] Der Text selbst ist kein richtiges Latein, schon das erste Wort „Lorem“ existiert nicht. „Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum, quia dolor sit, amet, consectetur, adipisci velit […]“ (Ferner gibt es auch niemanden, der den Schmerz um seiner selbst willen liebt, der ihn sucht und haben will, einfach, weil es Schmerz ist […]). Als Platzhaltertext sollen Lorem-ipsum-Passagen seit dem 16. Praktikabilität[Bearbeiten] Weblinks[Bearbeiten] Einzelnachweise[Bearbeiten] Gesprochene Version[Bearbeiten]

Cicero | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Marcus Tullius Cicero was born on January 3, 106 B.C.E. and was murdered on December 7, 43 B.C.E. His life coincided with the decline and fall of the Roman Republic, and he was an important actor in many of the significant political events of his time, and his writings are now a valuable source of information to us about those events. He was, among other things, an orator, lawyer, politician, and philosopher. While Cicero is currently not considered an exceptional thinker, largely on the (incorrect) grounds that his philosophy is derivative and unoriginal, in previous centuries he was considered one of the great philosophers of the ancient era, and he was widely read well into the 19th century. Table of Contents 1. Cicero's political career was a remarkable one. Instead, Cicero chose a career in the law. The next few years were very turbulent, and in 60 B.C.E. Caesar was murdered by a group of senators on the Ides of March in 44 B.C.E. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. i. j. k.

Lorem Ipsum - All the facts - Lipsum generator Ancient Rome - Ancient History The decadence and incompetence of Commodus (180-192) brought the golden age of the Roman emperors to a disappointing end. His death at the hands of his own ministers sparked another period of civil war, from which Lucius Septimius Severus (193-211) emerged victorious. During the third century Rome suffered from a cycle of near-constant conflict. A total of 22 emperors took the throne, many of them meeting violent ends at the hands of the same soldiers who had propelled them to power. Meanwhile, threats from outside plagued the empire and depleted its riches, including continuing aggression from Germans and Parthians and raids by the Goths over the Aegean Sea. The reign of Diocletian (284-305) temporarily restored peace and prosperity in Rome, but at a high cost to the unity of the empire. The stability of this system suffered greatly after Diocletian and Maximian retired from office. Access hundreds of hours of historical video, commercial free, with HISTORY Vault.

Lorem Ipsum - All the facts - Lipsum generator Ancient Roman Philosophy Ancient Roman Philosophy Hall of Philosophers Philosophers Pliny The Elder Plotinus Roman Virtues Education A final level of education was philosophical study. The single most important philosophy in Rome was Stoicism, which originated in Hellenistic Greece. After the death of Zeno of Citium, the Stoic school was headed by Cleanthes and Chrysippus, and its teachings were carried to Rome in 155 by Diogenes of Babylon. Stoic ideas appear in the greatest work of Roman literature, Vergil's Aeneid , and later the philosophy was adopted by Seneca (c. 1-65 A.D.), Lucan (39-65; poet and associate of the Emperor Nero), Epictetus (c. 55-135; see passages from the and the Emperor Marcus Aurelius (born 121, Emperor 161-180; author of the Stoicism is perhaps the most significant philosophical school in the Roman Empire, and much of our contemporary views and popular mythologies about Romans are derived from Stoic principles. Logos is a linguistic term; it refers particularly to the meanings of words.

|| Blindtext-Generator | Lorem ipsum für Webdesigner || Latin Poetry Podcast Abracadabra mortiferum magis est quod Graecis hemitritaeos vulgatur verbis; hoc nostrā dicere linguā non potuēre ulli, puto, nec voluere parentes. inscribes chartae quod dicitur abracadabra saepius et subter repetes, sed detrahe summam et magis atque magis desint elementa figuris singula, quae semper rapies, et cetera figes, donec in angustum redigatur littera conum : his lino nexis collum redimire memento. nonulli memorant adipem prodesse leonis. Quinctius Serenus Sammonicus, Liber Medicinalis 923-941 (ed. Vollmer in Corpus Medicorum Latinorum 3.2, Leipzig: Teubner, 1916). The work seems to date from the 2nd to the 4th centuries AD, and is usually assigned by scholars to around AD 200, based on the dubious identification of the author as Serenus Sammonicus, a scholar and moral critic of the age of Septimius Severus. Vollmer sensibly suggests linques or scribes for figes, which he believes is a corruption carried over from figura in the previous line. Here is my translation:

Lorem ipsum - Generator und Informationen The Roman Way Romanitas, in Nova Roma, refers to the general study and practice of Roman culture. It is the direct application of Roman ethics, virtues, and philosophies in our everyday life, and it is one of the main goals of Nova Roma to promote the Romanitas and the mos maiorum among its citizens. As with all aspects of Nova Roma, the extent to which any given citizen indulges in this area is up to his or her own inclination; but it is certainly encouraged. This includes the learning and use of the Latin language, the study and reenactment of Roman arts (including historical civil or military reenactments), the production of Roman drama, the study of Roman history, and a wide variety of other pursuits. It is as part of the mos maiorum that citizens are expected to take up Roman names for use within our society. As with all things that make up the Roman culture, the emphasis is on the practical application of these arts and this knowledge in our everyday lives.

Loripsum.net - The 'lorem ipsum' generator that doesn't suck.