Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

Brazilian jiu-jitsu (/dʒuːˈdʒɪtsuː/; Portuguese: [ˈʒiw ˈʒitsu], [ˈʒu ˈʒitsu], [dʒiˈu dʒiˈtsu]) (BJJ; Portuguese: jiu-jitsu brasileiro) is a martial art, combat sport, and a self defense system that focuses on grappling and especially ground fighting. Brazilian jiu-jitsu was formed from Kodokan Judo ground fighting (newaza) fundamentals that were taught by a number of individuals including Takeo Yano, Mitsuyo Maeda and Soshihiro Satake. Brazilian jiu-jitsu eventually came to be its own art through the experiments, practices, and adaptation of the judo knowledge of Carlos and Hélio Gracie, who then passed their knowledge on to their extended family. History[edit] Origins[edit] Geo Omori opened the first jujutsu / judo school in Brazil in 1909. [5] He would go on to teach a number of individuals including Luiz França. Gastão Gracie was a business partner of the American Circus in Belém. Name[edit] Some confusion has arisen over the employment of the term 'jiudo'. Prominence[edit] Guards[edit]

Qi

Etymology[edit] The etymological explanation for the form of the qi logogram (or chi) in the traditional form 氣 is "steam (气) rising from rice (米) as it cooks". The earliest way of writing qi consisted of three wavy lines, used to represent one's breath seen on a cold day. A later version, 气, identical to the present-day simplified character, is a stylized version of those same three lines. Definition[edit] References to concepts analogous to the qi taken to be the life-process or flow of energy that sustains living beings are found in many belief systems, especially in Asia. Within the framework of Chinese thought, no notion may attain such a degree of abstraction from empirical data as to correspond perfectly to one of our modern universal concepts. The ancient Chinese described it as "life force". Although the concept of qi has been important within many Chinese philosophies, over the centuries the descriptions of qi have varied and have sometimes been in conflict. Pronunciation[edit]

Hapkido

The art adapted from Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu (大東流合気柔術) as it was taught by Choi Yong-Sool (Hangul: 최용술) when he returned to Korea after World War II, having lived in Japan for 30 years. This system was later combined with kicking and striking techniques of indigenous and contemporary arts such as taekkyeon, as well as throwing techniques and ground fighting from Japanese Judo. Its history is obscured by the historical animosity between the Korean and Japanese people following the Second World War.[1][2][3][4] Name[edit] Hapkido is rendered "합기도" in the native Korean writing system known as hangul, the script used most widely in modern Korea. The character 合 hap means "coordinated" or "joining"; 氣 ki describes internal energy, spirit, strength, or power; and 道 do means "way" or "art", yielding a literal translation of "joining-energy-way". Although aikido and hapkido are believed by many to share a common history, they remain separate and distinct from one another. Choi Yong-Sool[edit]

Morihei Ueshiba

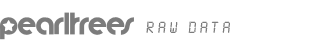

Morihei Ueshiba (植芝 盛平, Ueshiba Morihei?, December 14, 1883 – April 26, 1969) was a famous martial artist and founder of the Japanese martial art of aikido. He is often referred to as "the founder" Kaiso (開祖?) or Ōsensei (大先生/翁先生?), "Great Teacher". The son of a landowner from Tanabe, Ueshiba studied a number of martial arts in his youth, and served in the Japanese Army during the Russo-Japanese War. Ueshiba moved to Tokyo in 1926, where he set up the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. Early years[edit] Morihei Ueshiba was born in Tanabe, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan on December 14, 1883, the fourth child (and only son) born to Yoroku Ueshiba and his wife Yuki.[1][2]:5–10 Morihei was raised in a somewhat privileged setting. At the age of six Ueshiba was sent to study at the Jizōderu Temple, but had little interest in the rote learning of Confucian education. In 1903, Ueshiba was called up for military service. Ueshiba is known to have studied several martial arts during his early life. Hokkaidō[edit] ...

Jujutsu

Jujutsu (/dʒuːˈdʒuːtsuː/; Japanese: 柔術, jūjutsu listen , Japanese pronunciation: [ˈdʑɯɯ.dʑɯ.tsɯ]) is a Japanese martial art and a method of close combat for defeating an armed and armored opponent in which one uses no weapon or only a short weapon.[1][2] The word jujutsu can be spelled as ju-jitsu/jujitsu, ju-jutsu. "Jū" can be translated to mean "gentle, soft, supple, flexible, pliable, or yielding." "Jutsu" can be translated to mean "art" or "technique" and represents manipulating the opponent's force against himself rather than confronting it with one's own force.[1] Jujutsu developed among the samurai of feudal Japan as a method for defeating an armed and armored opponent in which one uses no weapon, or only a short weapon.[3] Because striking against an armored opponent proved ineffective, practitioners learned that the most efficient methods for neutralizing an enemy took the form of pins, joint locks, and throws. History[edit] Origins[edit] Development[edit] Description[edit]

Dojo

The concept of a dōjō only referring to a training place specifically for Asian martial arts is a Western concept; in Japan, any physical training facility, including professional wrestling schools, may be called dōjō because of its close martial arts roots.[2] In martial arts[edit] A proper Japanese martial arts dōjō is considered special and is well cared for by its users. Shoes are not worn in a dōjō. Many traditional dōjō follow a prescribed pattern with shomen ("front") and various entrances that are used based on student and instructor rank laid out precisely. The Noma dōjō in Tokyo is an example of the old kendō dōjō within modern kendo. Hombu dōjō[edit] A hombu dōjō of a style is the administrative and stylistic headquarters of a particular martial arts style or group. Some well-known dōjō located in Japan are: Other names for training halls[edit] Other names for training halls that are equivalent to "dojo" include the following: In Zen Buddhism[edit] References[edit]

Taiji Quan

Medical research has found evidence that t'ai chi is helpful for improving balance and for general psychological health, and that it is associated with general health benefits in older people.[2] Overview[edit] . T'ai chi ch'uan theory and practice evolved in agreement with many Chinese philosophical principles, including those of Taoism and Confucianism. T'ai chi ch'uan training involves five elements, taolu (solo hand and weapons routines/forms), neigong & qigong (breathing, movement and awareness exercises and meditation), tuishou (response drills) and sanshou (self defence techniques). While t'ai chi ch'uan is typified by some for its slow movements, many t'ai chi styles (including the three most popular – Yang, Wu, and Chen) – have secondary forms with faster pace. It is purported that focusing the mind solely on the movements of the form helps to bring about a state of mental calm and clarity. Some other forms of martial arts require students to wear a uniform during practice. Note: