Bio The first 300 words from Wabi-Sabi: for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers “Wabi-sabi is a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. It is a beauty of things modest and humble. It is a beauty of things unconventional.” “The immediate catalyst for this book was a widely publicized tea event in Japan. The Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi has long been associated with the tea ceremony, and this event promised to be a profound wabi-sabi experience. “Admittedly, the beauty of wabi-sabi is not to everyone’s liking. Undesigning the Bath Gardens of Gravel and Sand 13 Books Arranging Things: A Rhetoric of Object PlacementThe Flower Shop: Charm, Grace, Beauty, Tenderness in a Commercial Context Which "Aesthetics" Do You Mean? Quilling - Turning Paper Strips into Intricate Artworks Quilling has been around for hundreds of years, but it’s still as impressive and popular now as it was during the Renaissance. The art of quilling first became popular during the Renaissance, when nuns and monks would use it to roll gold-gilded paper and decorate religious objects, as an alternative to the expensive gold filigree. Later, during the 18th and 19th centuries, it became a favorite pass-time of English ladies who created wonderful decorations for their furniture and candles, through quilling. Basically, the quilling process consists of cutting strips of paper, and rolling them with a special tool. Because it requires so few supplies, quilling is available to anyone with enough patience to give it a try, and with a little bit of practice you’ll be creating some pretty amazing paper artworks, just like iron-maiden-art, whose works I think show the beauty of quilling. Reddit Stumble

Wabi-Sabi The Japanese view of life embraced a simple aesthetic that grew stronger as inessentials were eliminatedand trimmed away. -architect Tadao Ando Pared down to its barest essence, wabi-sabi is the Japanese art of finding beauty in imperfection and profundity in nature, of accepting the natural cycle of growth, decay, and death. It's simple, slow, and uncluttered-and it reveres authenticity above all. Wabi-sabi is flea markets, not warehouse stores; aged wood, not Pergo; rice paper, not glass. Wabi-sabi is underplayed and modest, the kind of quiet, undeclared beauty that waits patiently to be discovered. Daisetz T. In Japan, there is a marked difference between a Thoreau-like wabibito (wabi person), who is free in his heart, and a makoto no hinjin, a more Dickensian character whose poor circumstances make him desperate and pitiful. The words wabi and sabi were not always linked, although they've been together for such a long time that many people (including D. Cleanliness implies respect.

Mottainai Mottainai (もったいない?, [mottainai]) is a Japanese term conveying a sense of regret concerning waste.[1] The expression "Mottainai!" can be uttered alone as an exclamation when something useful, such as food or time, is wasted, meaning roughly "what a waste!" Mottainai is an old Buddhist word, which has ties "with the Shinto idea that objects have souls Usage and translation[edit] Mottainai in Japanese refers to more than just physical waste (resources). As an exclamation ("mottainai!") History[edit] Origins[edit] In ancient Japanese, mottainai had various meanings, including a sense of gratitude mixed with shame for receiving greater favor from a superior than is properly merited by one's station in life.[1] One of the earliest appearances of the word mottainai is in the book Genpei Jōsuiki (A Record of the Genpei War, ca. 1247).[8] Mottainai is a compound word, mottai+nai.[9] Mottai (勿体?) Mottai was originally used in the construction mottai-ga-aru (勿体が有る? Efforts to revive the tradition[edit]

Feng shui Feng shui ( i/ˌfɛŋ ˈʃuːi/;[1] i/fʌŋ ʃweɪ/;[2] pinyin: fēng shuǐ, pronounced [fɤ́ŋ ʂwèi] ( )) is a Chinese philosophical system of harmonizing everyone with the surrounding environment. Historically, feng shui was widely used to orient buildings—often spiritually significant structures such as tombs, but also dwellings and other structures—in an auspicious manner. Qi rides the wind and scatters, but is retained when encountering water.[3] Feng shui was suppressed in mainland China during the cultural revolution in the 1960s, but since then has increased in popularity. Modern reactions to feng shui are mixed. History[edit] Origins[edit] Cosmography that bears a striking resemblance to modern feng shui devices and formulas appears on a piece of jade unearthed at Hanshan and dated around 3000 BC. Beginning with palatial structures at Erlitou,[12] all capital cities of China followed rules of feng shui for their design and layout. Early instruments and techniques[edit] Foundation theories[edit] East

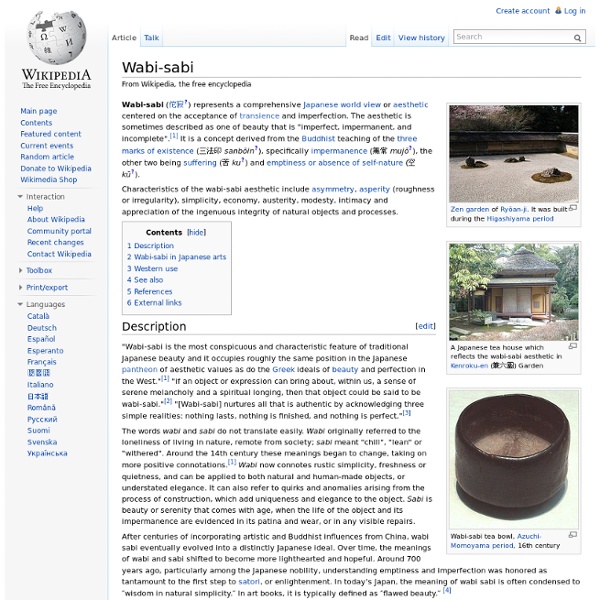

Wabi-sabi Wabi-sabi (侘・寂, Wabi-sabi?) es un término estético japonés que describe objetos o ambientes caracterizados por su simpleza rústica. El wabi-sabi combina la atención a la composición del minimalismo, con la calidez de los objetos provenientes de la naturaleza. Características[editar] Corriente japonesa estética y de comprensión del mundo basada en la fugacidad e impermanencia. Según Leonard Koren, autor del libro Wabi-Sabi: for Artists, Designers, Poets and Philosophers, se refiere a aquella belleza imperfecta, impermanente e incompleta. El wabi-sabi ocupa la misma posición en la estética japonesa que en Occidente ocupan los ideales griegos de belleza y perfección. Andrew Juniper afirma que: Si un objeto o expresión puede provocar en nosotros una sensación de serena melancolía y anhelo espiritual, entonces dicho objeto puede considerarse wabi-sabi. Richard R. Las palabras wabi y sabi no se traducen fácilmente. Ambos conceptos, wabi y sabi, sugieren sentimientos de desconsuelo y soledad.

Everything but the Paper Cut: Eye-popping Ways Artists Use Paper In the year since the Museum of Art and Design reopened in its new digs on Columbus Circle, they've been delivering consistently compelling shows--from punk-rock lace to radical knitting experiments. The newest, "Slash: Paper Under the Knife", opened last weekend and runs through April 4, 2010. The focus is paper--and the way contemporary artists have used paper itself as a medium, whether by cutting, tearing, burning, or shredding. In all, the show features 50 artists and a dozen installations made just for the show, including Andreas Kocks's Paperwork #701G (in the Beginning), seen above. Mia Pearlman's Eddy: Ferry Staverman, A Space Odesey: A detail of a sprawling work by Andrew Scott Ross, Rocks and Rocks and Caves and Dreams: Lane Twitchell's Peaceable Kingdom (Evening Land): Béatrice Coron, WaterCity: Between the Lines, by Ariana Boussard-Reifel: A book with every single word cut out: Chris Kenny's Grand Island, part of a series of "maps" depicting a fictional city:

LifeEdited Given both the small footprint of the existing apartment and the quite high number of desired functions that should be fitted inside of it, we thought the most logical solution would be to draw a line between the convertible and non-convertible areas. So for the starting point of the concept, we decided that the best configuration of the apartment would have the wet and non-convertible areas (the kitchen and the bathroom) positioned next to the eastern wall facing the building's private courtyard, using the rest as the convertible area ,a confortable sized open space, receiving natural light from all four windows and meeting all the owners needs ,by transforming itself. The main area of the apartment is a convertible room,by using smart space saving furniture systems, combined with the mobility of the modular piece on the entrance wall. Also there is a thinbike slot behind the folding dining table that can be accesed from the entrance area.

Memento mori Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation by Hans Memling. This triptych contrasts earthly beauty and luxury with the prospect of death and hell. The outer panels of Rogier van der Weyden's Braque Triptych shows the skull of the patron displayed in the inner panels. The bones rest on a brick, a symbol of his former industry and achievement.[1] Memento mori (Latin: "remember (that you have) to die"[2]) is the medieval Latin theory and practice of reflection on mortality, especially as a means of considering the vanity of earthly life and the transient nature of all earthly goods and pursuits. In art, memento mori are artistic or symbolic reminders of mortality.[2] In the European Christian art context, "the expression... developed with the growth of Christianity, which emphasized Heaven, Hell, and salvation of the soul in the afterlife Historic usage[edit] Classical[edit] Europe — Medieval through Victorian[edit] Prince of OrangeRené of Châlon died in 1544 at age 25. Use by religious[edit]