Orion From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search Orion () may refer to: Common meanings[edit] Arts and media[edit] Fictional entities[edit] Characters and species[edit] Vessels[edit] Literature[edit] Music[edit] Albums and long compositions[edit] Songs[edit] Other uses in music[edit] Periodicals[edit] Other uses in arts and media[edit] Buildings[edit] Companies[edit] Arts and media[edit] Orion Pictures, an American film production companyOrion Publishing Group, a UK-based book publisherOrion Records (1960s–'80s), a classical record label Electrical power and electronics[edit] Orion Electric, a Japanese electronics companyOrion Electronics, a Hungarian companyOrion Energy Systems, an American power technology companyOrion New Zealand Limited, a New Zealand electricity distribution company Food and beverage[edit] Orion Breweries, the fifth-largest beer brewery in JapanOrion Confectionery, a South Korean confectionery company Transportation and vehicles[edit] Other companies[edit] [edit]

Messier 41 Messier 41 (also known as M41 or NGC 2287) is an open cluster in the Canis Major constellation. It was discovered by Giovanni Batista Hodierna before 1654 and was perhaps known to Aristotle about 325 BC.[3] M41 lies about four degrees almost exactly south of Sirius, and forms a triangle with it and Nu2 Canis Majoris—all three can be seen in the same field in binoculars. The cluster itself covers an area around the size of the full moon.[4] It contains about 100 stars including several red giants, the brightest being a spectral type K3 giant of apparent magnitude 6.3 near the cluster's center, and a number of white dwarfs.[5][6][7] The cluster is estimated to be moving away from us at 23.3 km/s.[1] The diameter of the cluster is between 25 and 26 light years. Its age is estimated at between 190 and 240 million years old. Walter Scott Houston describes the appearance of the cluster in small telescopes:[8] Many visual observers speak of seeing curved lines of stars in M41. See also[edit]

Decline of ancient Egyptian religion The decline of indigenous religious practices in ancient Egypt is largely attributed to the spread of Christianity in Egypt, and its strict monotheistic nature not allowing the syncretism seen between ancient Egyptian religion and other polytheistic religions, such as that of the Romans. Although religious practices within Egypt stayed relatively constant despite contact with the greater Mediterranean world, such as with the Assyrians, the Persians, Greeks, and Romans, Christianity directly competed with the native religion. Even before the Edict of Milan in AD 313, which legalised Christianity in the Roman Empire, Egypt became an early centre of Christianity, especially in Alexandria where numerous influential Christian writers of antiquity such as Origen and Clement of Alexandria lived much of their lives, and native Egyptian religion may have put up little resistance to the permeation of Christianity into the province. Background[edit] Amarna heresy[edit] History[edit] Late Period[edit]

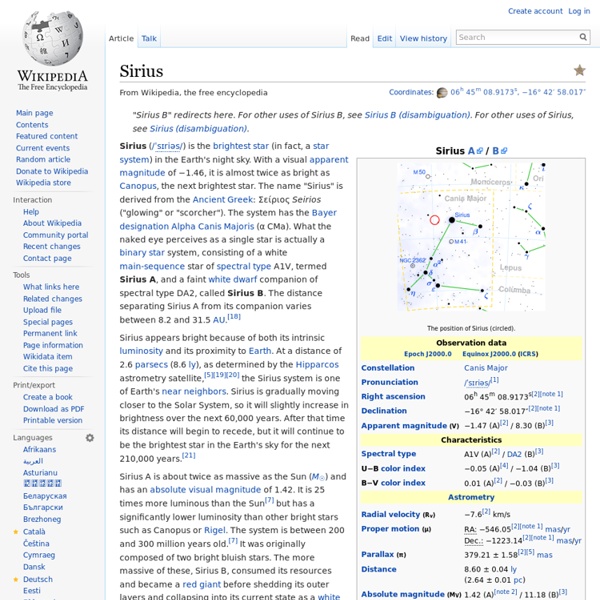

Canis Major An image of Canis Major (top right) as seen from an airplane at around 8 degrees north (Andaman Sea west of Thailand). Canis Major contains Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, known as the 'dog star'. It is bright because of its proximity to our Solar System. In contrast, the other bright stars of the constellation are stars of great distance and high luminosity. History and mythology[edit] In ancient Mesopotamia, Sirius was seen as an arrow, KAK.SI.DI, aiming towards Orion, while the southern stars of Canis Major and a part of Puppis were viewed as a bow, BAN in the Three Stars Each tablets, dating to around 1100 BC. In non-western astronomy[edit] Both the Maori people and the people of the Tuamotus recognized the figure of Canis Major as a distinct entity, though it was sometimes absorbed into other constellations. Canis Major as depicted in Urania's Mirror, a set of constellation cards published in London c.1825. Characteristics[edit] Notable features[edit] Stars[edit]

Heliacal rising Rising of stars prior to sunrise Cause and significance[edit] Relative to the stars, the Sun appears to drift eastward about one degree per day along a path called the ecliptic because there are 360 degrees in any complete revolution (circle), which takes about 365 days in the case of one revolution of the Earth around the Sun. The same star will reappear in the eastern sky at dawn approximately one year after its previous heliacal rising. Because the heliacal rising depends on the observation of the object, its exact timing can be dependent on weather conditions.[7] Heliacal phenomena and their use throughout history have made them useful points of reference in archeoastronomy.[8] Non-application to circumpolar stars[edit] Some stars, when viewed from latitudes not at the equator, do not rise or set. History[edit] Constellations containing stars that rise and set were incorporated into early calendars or zodiacs. Acronycal and cosmic(al)[edit] Overview[edit] See also[edit] Notes[edit]

Nile River in Africa and the longest river in the world The Nile (Arabic: النيل, written as al-Nīl; pronounced as an-Nīl[needs Arabic IPA]) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa, and is the longest river in Africa and the disputed longest river in the world,[2][3] as the Brazilian government says that the Amazon River is longer than the Nile.[4][5] The Nile, which is about 6,650 km (4,130 mi)[n 1] long, is an "international" river as its drainage basin covers eleven countries: Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, South Sudan, Republic of the Sudan, and Egypt.[7] In particular, the Nile is the primary water source of Egypt and Sudan.[8] The Nile has two major tributaries – the White Nile and the Blue Nile. The White Nile is considered to be the headwaters and primary stream of the Nile itself. The Blue Nile, however, is the source of most of the water and silt. Etymology and names[edit] Courses[edit] Sources[edit] St.

State church of the Roman Empire a form of Christianity in the Roman Empire With the Edict of Thessalonica in 380 AD, Emperor Theodosius I made Nicene Christianity the Empire's state religion.[1][2] The Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Catholic Church each claim to stand in continuity with the church to which Theodosius granted recognition, but do not look on it as specific to the Roman Empire. Justinian I, who became emperor in Constantinople in 527, recognized the patriarchs of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem as the top leadership of the Church (see Pentarchy). However, Justinian claimed "the right and duty of regulating by his laws the minutest details of worship and discipline, and also of dictating the theological opinions to be held in the Church".[3][4] History[edit] (16th century) (11th century) Early Christianity in relation to the state[edit] Before the end of the 1st century, the Roman authorities recognized Christianity as a separate religion from Judaism. Legacy[edit]

Diodorus Siculus Diodorus Siculus (; Koinē Greek: Διόδωρος Σικελιώτης Diodoros Sikeliotes) (fl. 1st century BCE) or Diodorus of Sicily was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history Bibliotheca historica, much of which survives, between 60 and 30 BCE. It is arranged in three parts. The first covers mythic history up to the destruction of Troy, arranged geographically, describing regions around the world from Egypt, India and Arabia to Europe. The second covers the Trojan War to the death of Alexander the Great. The third covers the period to about 60 BC. Life[edit] Work[edit] Bibliotheca historica, 1746 Diodorus' universal history, which he named Bibliotheca historica (Greek: Ἱστορικὴ Βιβλιοθήκη, "Historical Library"), was immense and consisted of 40 books, of which 1–5 and 11–20 survive:[4] fragments of the lost books are preserved in Photius and the excerpts of Constantine Porphyrogenitus. It was divided into three sections. See also[edit] Notes[edit]

Plutarch Plutarch (/ˈpluːtɑrk/; Greek: Πλούταρχος, Ploútarkhos, Koine Greek: [plǔːtarkʰos]; later named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus (Λούκιος Μέστριος Πλούταρχος);[a] c. 46 – 120 AD),[1] was a Greek historian, biographer, and essayist, known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia.[2] He is considered today to be a Middle Platonist. Early life[edit] Ruins of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, where Plutarch served as one of the priests responsible for interpreting the predictions of the oracle. Plutarch was born to a prominent family in the small town of Chaeronea about twenty miles east of Delphi in the Greek region known as Boeotia. His brothers, Timon and Lamprias, are frequently mentioned in his essays and dialogues, where Timon is spoken of in the most affectionate terms. The exact number of his sons is not certain, although two of them, Autobulus and second Plutarch, are often mentioned. At some point, Plutarch took up Roman citizenship.