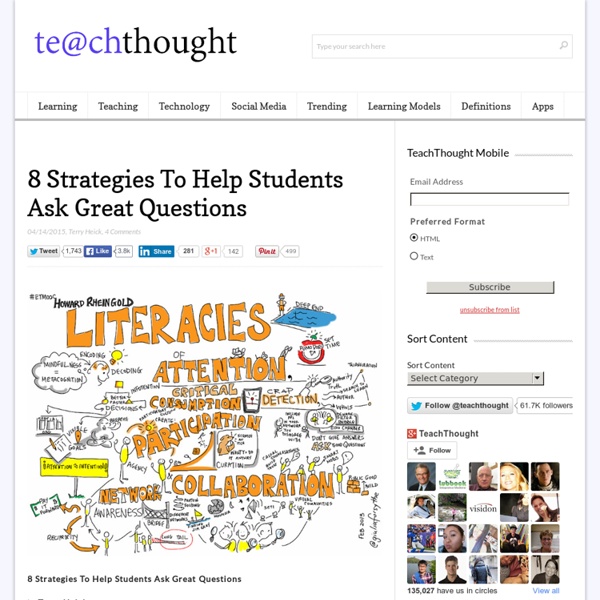

20 Questions To Guide Inquiry-Based Learning

20 Questions To Guide Inquiry-Based Learning Recently we took at look at the phases of inquiry-based learning through a framework, and even apps that were conducive to inquiry-based learning on the iPad. During our research for the phases framework, we stumbled across the following breakdown of the inquiry process for learning on 21stcenturyhsie.weebly.com (who offer the references that appear below the graphic). Most helpfully, it offers 20 questions that can guide student research at any stage, including: What do I want to know about this topic? These stages have some overlap with self-directed learning. References Cross, M. (1996). Kuhlthau, C., Maniotes, L., & Caspari, A. (2007).

Smart Strategies That Help Students Learn How to Learn

Teaching Strategies Bruce Guenter What’s the key to effective learning? One intriguing body of research suggests a rather riddle-like answer: It’s not just what you know. It’s what you know about what you know. To put it in more straightforward terms, anytime a student learns, he or she has to bring in two kinds of prior knowledge: knowledge about the subject at hand (say, mathematics or history) and knowledge about how learning works. In our schools, “the emphasis is on what students need to learn, whereas little emphasis—if any—is placed on training students how they should go about learning the content and what skills will promote efficient studying to support robust learning,” writes John Dunlosky, professor of psychology at Kent State University in Ohio, in an article just published in American Educator. “Teaching students how to learn is as important as teaching them content.” [RELATED: What Students Should Know About Their Own Brains] • What is the topic for today’s lesson? Related

A Quick Guide To Questioning In The Classroom

A Guide to Questioning in the Classroom by TeachThought Staff This post was promoted by Noet Scholarly Tools who are offering TeachThought readers 20% off their entire order at Noet.com with coupon code TEACHTHOUGHT (enter the coupon code after you’ve signed in)! Get started with their Harvard Fiction Classics or introductory packages on Greek and Latin classics. Noet asked us to write about inquiry because they believe it’s important, and relates to their free research app for the classics. This is part 1 of a 2-part series on questioning in the classroom. Something we’ve become known for is our focus on thought, inquiry, and understanding, and questions are a big part of that. If the ultimate goal of education is for students to be able to effectively answer questions, then focusing on content and response strategies makes sense. Why Questions Are More Important Than Answers The ability to ask the right question at the right time is a powerful indicator of authentic understanding.

Harvard Education Publishing Group - Home

Students in Hayley Dupuy’s sixth-grade science class at the Jane Lathrop Stanford Middle School in Palo Alto, Calif., are beginning a unit on plate tectonics. In small groups, they are producing their own questions, quickly, one after another: What are plate tectonics? How fast do plates move? Why do plates move? Do plates affect temperature? Far from Palo Alto, in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston, Mass., Sharif Muhammad’s students at the Boston Day and Evening Academy (BDEA) have a strikingly similar experience. These two students—one in Palo Alto, the other in Roxbury—are discovering something that may seem obvious: When students know how to ask their own questions, they take greater ownership of their learning, deepen comprehension, and make new connections and discoveries on their own. The origins of the QFT can be traced back 20 years to a dropout prevention program for the city of Lawrence, Mass., that was funded by the Annie E. The QFT has six key steps:

0188B251ED626B0C9ED674387ADAE37D4F main article 6650

Questioning - Top Ten Strategies

“Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow. The important thing is to not stop questioning.” – Albert Einstein Questioning is the very cornerstone of philosophy and education, ever since Socrates ( in our Western tradition) decided to annoy pretty much everyone by critiquing and harrying people with questions – it has been central to our development of thinking and our capacity to learn. Indeed, it is so integral to all that we do that it is often overlooked when developing pedagogy – but it as crucial to teaching as air is to breathing. Most research indicates that as much as 80% of classroom questioning is based on low order, factual recall questions. Effective questioning is key because it makes the thinking visible: it identifies prior knowledge; reasoning ability and the specific degree of student understanding – therefore it is the ultimate guide for formative progress. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Q1. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Added Extras: Like this: Like Loading...

Great Questions Make for Great Science Education | Concord Consortium

By Amy Pallant and Sarah J. Pryputniewicz In science and in education, questions are guideposts. Figure 1. Learning to love questions is important. Educators know that sound teaching usually begins with a compelling question. The High-Adventure Science lessons Will there be enough fresh water? Explore the distribution, availability and usage of fresh water on Earth. What is the future of Earth's climate? Explore interactions between some of the factors that affect Earth's global temperature. Will the air be clean enough to breathe? Explore the sources and flow of pollutants through the atmosphere. What are our choices for supplying energy for the future? Explore the advantages and disadvantages of different energy sources used to generate electricity. Can we feed the growing population? Explore the resources that make up our agricultural system. Is there life in space? Explore how scientists are working to find life outside Earth. Start with the science Use computational models Analyze data

4 Questions Every Teacher Should Ask About Mobile Learning

4 Questions Every Teacher Should Ask About Mobile Learning by Justin Chando, Founder & CEO, Chalkup Untethered from desks, a tablet represents personalized learning potential for a student in ways we’re just catching up to. Truly; the promise of mobile is extraordinary. With every historical date ever needed for World History 101 suddenly contained in the back pocket of your average American eighth grader, we find ourselves in a new environment for learning. As I see an increase in creative ways to keep learning alive after class, I’m interested in thinking about what we should be doing to ensure schools can reap the full benefits of mobile. I’m not interested in seeing the same classes and materials we had a decade ago (but now with Chromebooks!) On the front end of this conversation, what I’ve come up with are questions. 4 Questions Teachers Should Ask About Mobile Learning In Their School What can we do with a device that we couldn’t previously? This is a tough one.