Detroit’s white population rises Detroit’s white population rose by nearly 8,000 residents last year, the first significant increase since 1950, according to a Detroit News analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. The data, made public Wednesday, mark the first time census numbers have validated the perception that whites are returning to a city that is overwhelmingly black and one where the overall population continues to shrink. Many local leaders contend halting Detroit’s population loss is crucial, and the new census data shows that policies to lure people back to the city may be helping stem the city’s decline. “It verifies the energy you see in so many parts of Detroit and it’s great to hear,” said Kevin Boyle, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and historian who studies the intersection of class, race, and politics in 20th-century America. “The last thing I want to do is dampen the good news, but the problem is Detroit is still the poorest city in the U.S. “I think it’s a trend. “It’s not creating an even playing field.”

Detroit’s Bankruptcy Reflects a History of Racism This is black history month. It is also the month that the Emergency Manager who took political power and control from the mostly African American residents of Detroit has presented his plan to bring the city out of the bankruptcy he steered it into. This is black history in the making, and I hope the nation will pay attention to who wins and who loses from the Emergency Manager’s plan. Black people are by far the largest racial or ethnic population in Detroit, which has the highest percentage of black residents of any American city with a population over 100,000. Detroit’s bankruptcy plan calls for the near-elimination of the retiree health benefits that city workers earned over the years, as well as drastic cuts in the pensions that retired and current workers have earned and counted on. It’s important to view what is happening to Detroit and its public employees through a racial lens. Government was involved at a more micro level as well. So, why is Detroit bankrupt?

State prepares to collect city income taxes for Detroit Detroiters and people who work in the city will be able to pay their individual city income taxes electronically starting with the next tax season after the state Treasury Department begins processing the city’s income tax collections in January, officials said today. The state is taking over Detroit income tax collection as part of the city’s post-bankruptcy efforts to improve its bottom line, and the Treasury Department will begin processing the taxes in January. The move will make it easier to file taxes while also boosting compliance, likely resulting in increased revenue for the city, the officials said. “Taxpayers deserve an easy and convenient filing process and the ability to e-file directly with the state will do just that,” Detroit Chief Financial Officer John Hill said in a news release. Income tax – 2.4% for residents and 1.2% for nonresidents who work in Detroit – is the city’s largest revenue source, estimated to raise more than $250 million a year.

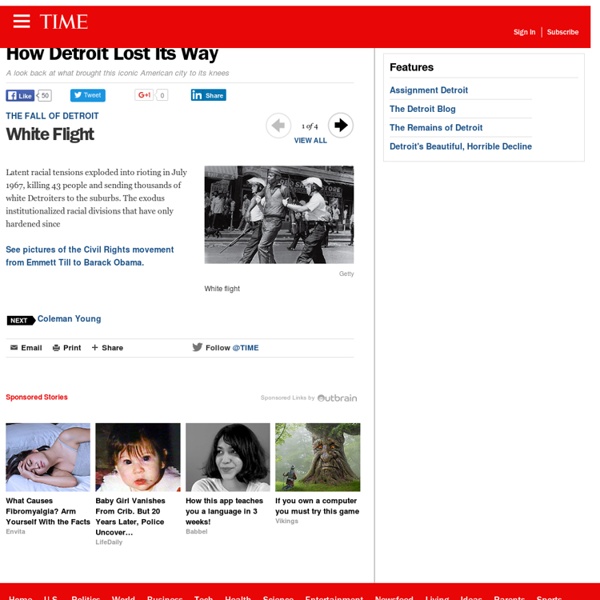

Whites moving into Detroit, blacks moving out as city shrinks overall - Crain's Detroit Business White people are moving back to Detroit, the American city that came to epitomize white flight, even as black people continue to leave for the suburbs and the city's overall population shrinks. Detroit is the latest major city to see an influx of whites who may not find the suburbs as alluring as their parents and grandparents did in the last half of the 20th century. Unlike New York, San Francisco and many other cities that have seen the demographic shift, though, it's cheap housing and incentive programs that are partly fueling the regrowth of the Motor City's white population. "For any individual who wants to build a company or contribute to the city, Detroit is the perfect place to be," said Bruce Katz, co-director of the Global Cities Initiative at the Washington, D.C. No other city may be as synonymous as Detroit with white flight, the exodus of whites from large cities that began in the middle of the last century. In the three years after the 2010 U.S. Elizabeth St. St.

A Dream Still Deferred AT first glance, the numbers released by the Census Bureau last week showing a precipitous drop in Detroit’s population — 25 percent over the last decade — seem to bear a silver lining: most of those leaving the city are blacks headed to the suburbs, once the refuge of mid-century white flight. But a closer analysis of the data suggests that the story of housing discrimination that has dominated American urban life since the early 20th century is far from over. In the Detroit metropolitan area, blacks are moving into so-called secondhand suburbs: established communities with deteriorating housing stock that are falling out of favor with younger white homebuyers. If historical trends hold, these suburbs will likely shift from white to black — and soon look much like Detroit itself, with resegregated schools, dwindling tax bases and decaying public services.

Detroit, General Motors and the American Dream In 1953 GM President Charles Erwin Wilson sat in front of a committee of senators during his confirmation hearing as President Eisenhower’s Secretary of Defense and famously said that “for years I thought that what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa.” The comment caused a brief firestorm of controversy because it seemed such a shameless expression of corporate greed and self-interest, and it forced Wilson to divest himself of a considerable amount of GM stock so as to avoid a potential conflict of interest. Sixty years after that quip, however, it is becoming more and more apparent that Wilson was exactly wrong: what was good for General Motors has not proved to be good for the nation, nor, ironically, has it proved good for Detroit. What was good for General Motors in the post-war period was, simply put, suburbanization. In the 1950s and ‘60s we became a nation disproportionately dependent on our cars.

The Detroit Bankruptcy The Detroit Bankruptcy The City of Detroit’s bankruptcy was driven by a severe decline in revenues (and, importantly, not an increase in obligations to fund pensions). Depopulation and long-term unemployment caused Detroit’s property and income tax revenues to plummet. The state of Michigan exacerbated the problems by slashing revenue it shared with the city. The city’s overall expenses have declined over the last five years, although its financial expenses have increased. The Shortfall Detroit’s emergency manager, Kevyn Orr, asserts that the city is bankrupt because it has $18 billion in long-term debt. Cash flow crisis. In a corporate bankruptcy, the judge takes stock of a company’s total assets and liabilities because the company can be liquidated and all its assets sold to pay down its debts. This means that Detroit is bankrupt not because of its outstanding debt, but because it is no longer bringing in enough revenue to cover its immediate expenses. Total outstanding debt. Revenue

Eight Mile Road | Detroit Historical Society Eight Mile Road was originally a dirt road that was designated as M-102 in 1928. Gradually, the road was widened and extended. Currently it exists in most areas as an eight-lane road, spanning more than 20 miles across metropolitan Detroit. Its more popular name is derived from the Detroit area’s Mile Road System. This system helps to identify streets running east-west throughout the region, beginning at the downtown intersection of Woodward and Michigan Avenue near the Detroit River. On a map, Eight Mile separates Wayne and Washtenaw counties from Macomb, Oakland, and Livingston, and Macomb counties. Eight Mile Road also played a role in one of the most notable controversies of famed Detroit Mayor Coleman A. Along its most impoverished sections, Eight Mile Road has, for several decades, been a destitute, dangerous strip of suffering businesses and broken windows. View all items related to Eight Mile Road

Detroit Arcadia | Essay | Rebecca Solnit Until recently there was a frieze around the lobby of the Hotel Pontchartrain in downtown Detroit, a naively charming painting of a forested lakefront landscape with Indians peeping out from behind the trees. The hotel was built on the site of Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, the old French garrison that three hundred years ago held a hundred or so pioneer families inside its walls while several thousand Ottawas and Hurons and Potawatomis went about their business outside, but the frieze evoked an era before even that rude structure was built in the lush woodlands of the place that was not yet Michigan or the United States. Scraped clear by glaciers during the last ice age, the landscape the French invaded was young, soggy, and densely forested. Fort Pontchartrain was never meant to be the center of a broad European settlement. It was a trading post, a garrison, and a strategic site in the scramble between the British and the French to dominate the North American interior.

Eight miles of murder Even by the low standards of Eight Mile Road, the Triple C bar was a seedy place to die. It is a squat one-storey building, windowless and dingy. The only hint at the nightclub inside is three white 'C's tacked to a dirty wall. It was here last week that local Detroit rapper 'Proof' died in a gun battle. To many, Eight Mile is a familiar name - made famous by the semi-autobiographical movie of the same name by rapper Eminem. But unlike the white rapper Eminem, the black Proof - real name DeShaun Holton - showed that most people do not escape Eight Mile. But Eight Mile means far more than another dead Detroit rapper, far more than one successful movie. Walking from one side of Eight Mile Road to the other is a jarring experience. In Detroit the unemployment rate is 14.1 per cent, more than double the national average. That decision goes to the core of the problem: race. The second blow to Detroit was one of employment. The city has experienced a flowering of talented rappers.

Fixing Detroit’s Broken School System: Improve accountability and oversight for district and charter schools Detroit is a classic story of a once-thriving city that has lost its employment base, its upper and middle classes, and much of its hope for the future. The city has been on a long, slow decline for decades. It’s difficult to convey the postapocalyptic nature of Detroit. Miles upon miles of abandoned houses are in piles of rot and ashes. There are new federal funds and private investment being directed to Detroit’s renewal. In January 2014, as part of a multicity study, researchers from the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) met with a dozen parents in Detroit to learn about their experiences with education in the city. Ms. Today, Detroit is a “high-choice” city. In Detroit, as was the case in the other cities we studied, parents struggle to navigate the city’s complex education marketplace and find quality options for their children. School Choice with Few Options Poor performance plagues schools in both DPS and the city’s large charter sector. Navigation Trials 1. 2. 3. 4.

Fewest cops are patrolling Detroit streets since 1920s Detroit — There are fewer police officers patrolling the city than at any time since the 1920s, a manpower shortage that sometimes leaves precincts with only one squad car, posing what some say is a danger to cops and residents. Detroit has lost nearly half its patrol officers since 2000; ranks have shrunk by 37 percent in the past three years, as officers retired or bolted for other police departments amid the city's bankruptcy and cuts to pay and benefits. Left behind are 1,590 officers — the lowest since Detroit beefed up its police force to battle Prohibition bootleggers. "This is a crisis, and the dam is going to break," said Mark Diaz, president of the Detroit Police Officers Association. "It's a Catch-22: I know the city is broke, but we're not going to be able to build up a tax base of residents and businesses until we can provide a safe environment for them." Police Chief James Craig acknowledges he doesn't have as many officers as he'd like. Staffing challenges Deployment shuffle

Real Estate Market Trends for Los Angeles, CA Los Angeles market trends indicate an increase of $47,500 (8%) in median home sales over the past year. The average price per square foot for this same period rose to $526, up from $479. Map Data Map data ©2016 Google, INEGI Median Listing Price Median Sales Price in Los Angeles No. Median Rent in Los Angeles Open Homes Los Angeles, CA Safe Neighborhoods Los Angeles, CA