Laozi. Names[edit] In traditional accounts, Laozi's personal name is usually given as Li Er (李耳, Old *Rəʔ Nəʔ,[5] Mod.

Lǐ Ěr) and his courtesy name as Boyang (trad. 伯陽, simp. 伯阳, Old *Pˤrak-lang,[5] Mod. Bóyáng). Laozi itself is an honorific title: 老 (Old *rˤuʔ, "old, venerable"[5]) and 子 (Old *tsə′, "master"[5]). As a religious figure, he is worshipped under the name "Supreme Old Lord" (太上老君, Tàishàng Lǎojūn)[18] and as one of the "Three Pure Ones". Historical views[edit] In the mid-twentieth century, a consensus emerged among scholars that the historicity of the person known as Laozi is doubtful and that the Tao Te Ching was "a compilation of Taoist sayings by many hands The third story in Sima Qian states that Laozi grew weary of the moral decay of life in Chengzhou and noted the kingdom's decline.

Depiction of Laozi in E.T.C. A seventh-century work, the Sandong Zhunang ("Pearly Bag of the Three Caverns"), embellished the relationship between Laozi and Yinxi. Tao Te Ching. The Tao Te Ching,[1] Daodejing, or Dao De Jing (simplified Chinese: 道德经; traditional Chinese: 道德經; pinyin: Dàodéjīng), also simply referred to as the Laozi (Chinese: 老子; pinyin: Lǎozǐ),[2][3] is a Chinese classic text.

According to tradition, it was written around 6th century BC by the sage Laozi (or Lao Tzu, Chinese: 老子; pinyin: Lǎozǐ, literally meaning "Old Master"), a record-keeper at the Zhou dynasty court, by whose name the text is known in China. The text's true authorship and date of composition or compilation are still debated,[4] although the oldest excavated text dates back to the late 4th century BC.[2] The Wade–Giles romanization "Tao Te Ching" dates back to early English transliterations in the late 19th century; its influence can be seen in words and phrases that have become well established in English. "Daodejing" is the pinyin romanization. Text[edit] The Tao Te Ching has a long and complex textual history. Title[edit] Internal structure[edit] Principal versions[edit] Sun Tzu. Sun Tzu's historicity is uncertain.

Sima Qian and other traditional historians placed him as a minister to King Helü of Wu and dated his lifetime to 544–496 BC. Modern scholars accepting his historicity nonetheless place the existing text of The Art of War in the later Warring States period based upon its style of composition and its descriptions of warfare.[2] Traditional accounts state that the general's descendant Sun Bin also wrote a treatise on military tactics, also titled The Art of War. Since both Sun Wu and Sun Bin were referred to as Sun Tzu in classical Chinese texts, some historians believed them identical prior to the rediscovery of Sun Bin's treatise in 1972. Sun Tzu's work has been praised and employed throughout East Asia since its composition. The Art of War.

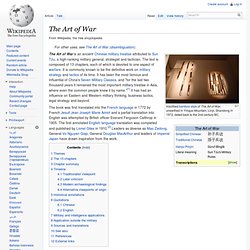

Inscribed bamboo slips of The Art of War, unearthed in Yinque Mountain, Linyi, Shandong in 1972, dated back to the 2nd century BC.

The Art of War is an ancient Chinese military treatise attributed to Sun Tzu, a high-ranking military general, strategist and tactician. The text is composed of 13 chapters, each of which is devoted to one aspect of warfare. It is commonly known to be the definitive work on military strategy and tactics of its time. It has been the most famous and influential of China's Seven Military Classics, and "for the last two thousand years it remained the most important military treatise in Asia, where even the common people knew it by name. The book was first translated into the French language in 1772 by French Jesuit Jean Joseph Marie Amiot and a partial translation into English was attempted by British officer Everard Ferguson Calthrop in 1905. Themes[edit] Sun Tzu considered war as a necessary evil that must be avoided whenever possible.