Classical antiquity. Early Middle Ages. TTC: Early Middle Ages. We often call them the "Dark Ages," the era which spanned the decline and fall of Rome's western empire and lingered for centuries, a time when the Ancient World was ending and Europe had seemingly vanished into ignorance and shadow, its literacy and urban life declining, its isolation$1#$ from the rest of the world increasing.

It was a time of decline, with the empire fighting to defend itself against an endless onslaught of attacks from all directions: the Vikings from the North, the Huns and other Barbarians from the East, the Muslim empire from the south. It was a time of death and disease, with outbreaks of plague ripping through populations both urban and rural. It was a time of fear, when religious persecution ebbed and flowed with the whims of those in power. And as Rome's power and population diminished, so, too, did its ability to handle the administrative burdens of an overextended empire. "A World Recognizably Becoming Our Own" Why Study "The Dark Ages"? View Less. Islamic Golden Age. Causes[edit] With a new, easier writing system and the introduction of paper, information was democratized to the extent that, probably for the first time in history, it became possible to make a living from simply writing and selling books.[4] The use of paper spread from China into Muslim regions in the eighth century CE, arriving in Spain (and then the rest of Europe) in the 10th century CE.

It was easier to manufacture than parchment, less likely to crack than papyrus, and could absorb ink, making it difficult to erase and ideal for keeping records. Islamic paper makers devised assembly-line methods of hand-copying manuscripts to turn out editions far larger than any available in Europe for centuries.[5] It was from these countries that the rest of the world learned to make paper from linen.[6] Philosophy[edit]

Muhammad. Names and appellations in the Quran Sources for Muhammad's life Quran A folio from an early Quran, written in Kufic script (Abbasid period, 8th–9th century). Umayyad conquest of Hispania. Al-Andalus under the Umayyads The Umayyad conquest of Hispania is the initial Islamic Umayyad Caliphate's conquest, between 711 and 788, of the Christian Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania, centered in the Iberian Peninsula, which was known to them under the Arabic name al-Andalus.

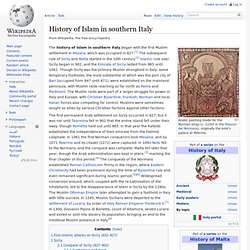

The conquest began with an invasion by an army that (according to traditional accounts) consisted largely of Berber Northwest Africans and was commanded by Tariq ibn Ziyad. They disembarked in early 711 at Gibraltar and campaigned their way northward. History of Islam in southern Italy. Arabic painting made for the Norman kings (c. 1150) in the Palazzo dei Normanni, originally the emir's palace at Palermo.

The history of Islam in southern Italy began with the first Muslim settlement in Mazara, which was occupied in 827.[1] The subsequent rule of Sicily and Malta started in the 10th century.[2] Islamic rule over Sicily began in 902, and the Emirate of Sicily lasted from 965 until 1061. Though Sicily was the primary Muslim stronghold in Italy, some temporary footholds, the most substantial of which was the port city of Bari (occupied from 847 until 871), were established on the mainland peninsula, with Muslim raids reaching as far north as Rome and Piedmont.

The Muslim raids were part of a larger struggle for power in Italy and Europe, with Christian Byzantine, Frankish, Norman and local Italian forces also competing for control. Muslims were sometimes sought as allies by various Christian factions against other factions. First Islamic attacks on Sicily (652–827)[edit] Holy Roman Empire. The empire grew out of East Francia, a primary division of the Frankish Empire.

Pope Leo III crowned Frankish king Charlemagne as emperor on Christmas 800, restoring the title in the West after more than three centuries. After Charlemagne died, the title passed in a desultory manner during the decline and fragmentation of the Carolingian dynasty, eventually falling into abeyance.[6] The title was revived in 962 when Otto I was crowned emperor, fashioning himself as the successor of Charlemagne[7] and beginning a continuous existence of the empire for over eight centuries.[6][8][9] Some historians refer to the coronation of Charlemagne as the origin of the empire,[10][11] while others prefer the coronation of Otto I as its beginning.[12][13] Scholars generally concur, however, in relating an evolution of the institutions and principles comprising the empire, describing a gradual assumption of the imperial title and role.[4][10] Name[edit] History[edit] Carolingian forerunners[edit]

Science in the Middle Ages. The history of science is the study of the historical development of science and scientific knowledge, including both the natural sciences and social sciences.

(The history of the arts and humanities is termed as the history of scholarship.) From the 18th century through late 20th century, the history of science, especially of the physical and biological sciences, was often presented in a progressive narrative in which true theories replaced false beliefs.[1] More recent historical interpretations, such as those of Thomas Kuhn, tend to portray the history of science in more nuanced terms, such as that of competing paradigms or conceptual systems in a wider matrix that includes intellectual, cultural, economic and political themes outside of science.[2]

Feudalism. Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries.

Broadly defined, it was a system for structuring society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour. Although derived from the Latin word feodum or feudum (fief),[1] then in use, the term feudalism and the system it describes were not conceived of as a formal political system by the people living in the medieval period. In its classic definition, by François-Louis Ganshof (1944),[2] feudalism describes a set of reciprocal legal and military obligations among the warrior nobility, revolving around the three key concepts of lords, vassals and fiefs.[2] There is also a broader definition, as described by Marc Bloch (1939), that includes not only warrior nobility but all three estates of the realm: the nobility, the clerics and the peasantry bonds of manorialism; this is sometimes referred to as a "feudal society". Definition. Bulgarian Empire. In the medieval history of Europe, Bulgaria's status as the Bulgarian Empire (Bulgarian: Българско царство, Balgarsko tsarstvo [ˈbəlɡɐrskʊ ˈt͡sarstvʊ]), wherein it acted as a key regional power (particularly rivaling Byzantium in Southeastern Europe[1]) occurred in two distinct periods: between the seventh and eleventh centuries, and again between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries.

The two "Bulgarian Empires" are not treated as separate entities, but rather as one state restored after a period of Byzantine rule over its territory. First Bulgarian Empire[edit] Macedonian dynasty. Basil I on horseback List of rulers[edit] Non-dynastic[edit] Michael VI (Μιχαήλ ΣΤ') (ruled 1056–1057) – chosen by Theodora; deposed and entered monastery Family tree[edit] See also[edit]

Plague of Justinian. Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire, alternatively known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the predominantly Greek-speaking eastern half continuation and remainder of the Roman Empire during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages.

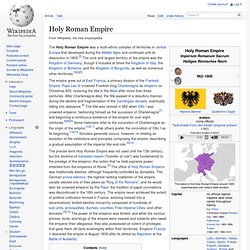

Its capital city was Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), originally founded as Byzantium. Migration Period. File:2000 Year Temperature Comparison.png. Viking expansion. Map showing area of Scandinavian settlement in the eighth (dark red), ninth (red), tenth (orange) centuries. Green denotes areas subjected to frequent Viking raids[image reference needed]. Note : the yellow colour in England and in the south of Italy does not have anything to do with the Vikings, but with the Normans from Normandy The Vikings sailed most of the North Atlantic, reaching south to North Africa and east to Russia, Constantinople and the Middle East, as looters, traders, colonists, and mercenaries. Vikings under Leif Ericson, heir to Erik the Red, reached North America, and set up a short-lived settlement in present-day L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Longer, more established settlements were formed in Greenland, Iceland, Great Britain, and Normandy. Motivation for expansion[edit] There's much debate among historians about what drove the Viking expansion.

Settlement demographics[edit] However, not all Viking settlements were primarily male. England[edit] Viking Age. Early Christianity. Byzantine Iconoclasm. A simple cross: example of iconoclast art in the Hagia Irene Church in Istanbul. Charlemagne.