Dualism (philosophy of mind) René Descartes's illustration of dualism.

Inputs are passed on by the sensory organs to the epiphysis in the brain and from there to the immaterial spirit. In philosophy of mind, dualism is the position that mental phenomena are, in some respects, non-physical,[1] or that the mind and body are not identical.[2] Thus, it encompasses a set of views about the relationship between mind and matter, and is contrasted with other positions, such as physicalism, in the mind–body problem.[1][2] Ontological dualism makes dual commitments about the nature of existence as it relates to mind and matter, and can be divided into three different types: Substance dualism asserts that mind and matter are fundamentally distinct kinds of substances.[1]Property dualism suggests that the ontological distinction lies in the differences between properties of mind and matter (as in emergentism).[1]Predicate dualism claims the irreducibility of mental predicates to physical predicates.[1]

Hypatia. Hypatia (/haɪˈpeɪʃə/ hy-PAY-shə; Ancient Greek: Ὑπατία; Hypatía) (born c.

AD 350 – 370; died 415[2]) was a Greek Alexandrine Neoplatonist philosopher in Egypt who was one of the earliest mothers of mathematics.[3] As head of the Platonist school at Alexandria, she also taught philosophy and astronomy.[4][5][6][7] As a Neoplatonist philosopher, she belonged to the mathematic tradition of the Academy of Athens, as represented by Eudoxus of Cnidus;[8] she was of the intellectual school of the 3rd century thinker Plotinus, which encouraged logic and mathematical study in place of empirical enquiry and strongly encouraged law in place of nature.[3] Life[edit] The mathematician and philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria was the daughter of the mathematician Theon Alexandricus (ca. 335–405).[13] She was educated at Athens.

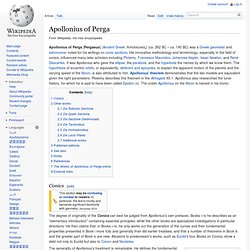

Death[edit] Events leading to her murder[edit] Ecclesiastical History, Socrates Scholasticus[27] Chronicle, John of Nikiu[28] Apollonius of Perga. Conics[edit] The degree of originality of the Conics can best be judged from Apollonius's own prefaces.

Books i–iv he describes as an "elementary introduction" containing essential principles, while the other books are specialized investigations in particular directions. He then claims that, in Books i–iv, he only works out the generation of the curves and their fundamental properties presented in Book i more fully and generally than did earlier treatises, and that a number of theorems in Book iii and the greater part of Book iv are new. Allusions to predecessor's works, such as Euclid's four Books on Conics, show a debt not only to Euclid but also to Conon and Nicoteles. Parabola connection with areas of a square and a rectangle, that inspired Apollonius of Perga to give the parabola its current name. The generality of Apollonius's treatment is remarkable. Other works[edit] Pappus mentions other treatises of Apollonius: De Rationis Sectione[edit] De Spatii Sectione[edit] De Tactionibus[edit]