Long-Term Unemployment: Anatomy of the Scourge. When unemployment rose during the Great Recession, so did long-term unemployment – defined here as joblessness lasting at least six months.

This is the norm in recessions, but the gravity of the problem after 2008 was unprecedented. In the 11 recessions since World War II, unemployment reached 9 percent in just three (1974-75, 1981-82, 2008-9). Only in the most recent slump, though, did the rate of longterm unemployment exceed 3 percent. Indeed, it reached 4.5 percent in April 2010, almost two percentage points higher than the peak in any previous postwar business cycle. The Human Disaster of Unemployment. Congress and Long-Term Unemployment. The talk in Washington these days is all about budget deficits, tax rates, and the “fiscal crisis” that supposedly looms in our near future.

But this chatter has eclipsed a much more pressing crisis here and now: almost thirteen million Americans are still unemployed. Though the job market has shown some signs of life in recent months, the latest figures on new jobs and on unemployment-insurance claims have been decidedly unimpressive. We are stuck with an unemployment rate three points higher than the postwar average, and the percentage of working adult Americans is as low as it’s been in almost thirty years. What’s most troubling is that so much of this unemployment is long-term. Forty per cent of the unemployed have been without a job for six months or more—a much higher rate than in any recession since the Second World War—and the average length of unemployment is about forty weeks, a number that has changed very little since 2010.

President Obama plans to propose a lower corporate tax rate, but Warren Buffett says that taxes aren't a key factor driving corporate investment. Yesterday, President Obama announced a long-awaited proposal to cut corporate taxes in America, which U.S. businesses complain are much too high by international standards.

The proposed reform is intended to prevent companies from shifting operations and earnings to tax havens (paging Mitt Romney!) And instead encourage companies to bring them back into the U.S., where they could create jobs and growth. What’s being missed in all this is that the corporate tax debate and the jobs debate are two separate things. Here’s why. America has the second highest corporate tax rate in the rich world. (MORE: The Corporate Tax Rate Is Lowest in Decades; Is Business Paying Its Fair Share?) That gets at the key issue: Fundamentally, lower taxes aren’t the reason that businesses choose to invest, or not, in a certain country.

True enough. Mean-Spirited, Bad Economics. By Simon Johnson The principle behind unemployment insurance is simple.

Since the 1930s, employers – and in some states employees — have paid insurance premiums (in the form of payroll taxes, levied on wages) to the government. If people are laid off through no fault of their own, they can claim this insurance – just like you file a claim on your homeowner’s or renter’s policy if your home burns down. Fire insurance is mostly sold by the private sector; unemployment insurance is “sold” by the government – because the private sector never performed this role adequately. A Quick Note on Wealth and Balance Sheet Debates. I still like using my map for understanding why people disagree on the best course of action on getting the economy going even if they are in agreement that something needs to be done.

Take this exchange in Democracy Journal – Arguing About Growth – between Larry Mishel of EPI and William Galston of Brookings Institute. Sustained, high joblessness causes lasting damage to wages, benefits, income, and wealth. The pain caused by persistently high unemployment is not limited to workers who are currently unemployed, a new Economic Policy Institute (EPI) briefing paper finds.

The economic damage extends to the broader workforce and the country in general through lost wages, income and wealth, as well as higher poverty. The national unemployment rate is currently 9.1%, and it has been at or above 8.8% for the past 28 months. The underemployment rate has remained between 15.7% and 17.4% since the spring of 2009, and it currently stands at 16.1%.

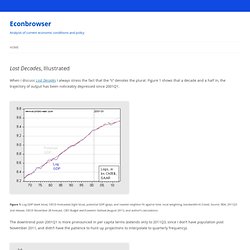

Sustained, high joblessness causes lasting damage to wages, benefits, income, and wealth by EPI President Lawrence Mishel and economist Heidi Shierholz explains that the monthly unemployment and underemployment rates do not capture the full picture of how many U.S. workers experience labor market distress. Roughly 31% of U.S. workers experienced unemployment or underemployment at some point in 2009. I>Lost Decades</I>, Illustrated. When I discuss Lost Decades I always stress the fact that the “s” denotes the plural.

Figure 1 shows that a decade and a half in, the trajectory of output has been noticeably depressed since 2001Q1. Figure 1: Log GDP (dark blue), OECD forecasted (light blue), potential GDP (gray), and nearest neighbor fit against time, local weighting, bandwidth=0.3 (red). Source: BEA, 2011Q3 2nd release, OECD November 28 forecast, CBO Budget and Economic Outlook (August 2011), and author’s calculations. The downtrend post-2001Q1 is more pronounced in per capita terms (extends only to 2011Q3, since I don’t have population post November 2011, and didn’t have the patience to hunt up projections to interpolate to quarterly frequency). Figure 2: Log per capita GDP (dark blue), potential GDP (gray), and nearest neighbor fit against time, local weighting, bandwidth=0.3 (red).

In Lost Decades, we make clear that we can avoid two complete lost decades, if we implemented reasonable policies. Fin du plein emploi. Underemployment in the United States.